( – promoted by lowkell)

And the winner is . . . Dominion Power!

And the winner is . . . Dominion Power!

Okay, you knew that. Dominion had the deck so stacked in its favor for Wednesday’s Virginia offshore wind lease auction that the question everyone was asking at the end wasn’t “who won?” but “who bid against Dominion, and why did they bother?”

The answer to the first question proved to be Charlottesville-based Apex Energy, a far more experienced player in the wind industry-but one without Dominion’s lock on the Virginia power market.

There was much to criticize about the auction format and the process that led inevitably to Dominion’s win, but this historic step is still hugely exciting for offshore wind advocates. If Dominion follows through on the commitment it just made to develop offshore wind, Virginia will be a winner, too.

That “if” has a lot of people worried, given that Dominion is both a participant in the offshore wind industry and one of its loudest detractors. Company executives talk about their desire to develop the lease area, and also their opinion that offshore wind energy is way too expensive to succeed. Often they make both points in the same conversation.

Observers can’t help wondering why a company would pour money into a venture if it doesn’t believe it can sell its own product. Two possible reasons come to mind: one, because it is willing to gamble on political and market changes that will make its venture successful after all; or two, because by spending the money to win the lease, the company prevents any competitor from occupying the space. One is gutsy, the other is evil. It is possible for both to be true.

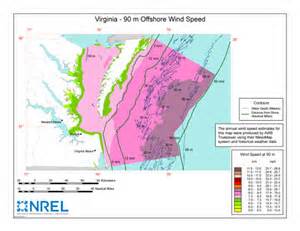

So what did Dominion win? The lease area, a 112,800-acre swath of ocean beginning more than 23 miles off Virginia Beach, is expected to support at least 2,000 megawatts of wind turbines-enough to power about 700,000 homes. It’s the second Wind Energy Area to be auctioned off in the U.S.; the first lies off Rhode Island and Massachusetts, and was auctioned off in August.

Under rules set by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the entire Virginia area was treated as one tract (a bad idea, in the view of advocates and industry members who aren’t Dominion, because it further reduced competition). Dominion won with a high bid of $1.6 million.

A formal announcement of the winning bid is expected in October, following federal antitrust review. As the winning bidder, Dominion will have five years to conduct the studies required for development of the area, with interim deadlines including submission of a Site Assessment Plan next summer.

After the five years is up, Dominion could decide not to proceed, releasing the area for BOEM to offer in a new auction. That result would be an unqualified disaster for Virginia’s ability to develop an offshore wind industry here. With states to the north proceeding, we would lose not just construction jobs, but the entire supply chain, and likely the marine services as well. Many thousands of jobs now ride on Dominion following through.

If Dominion decides to proceed, it will have to submit a Construction and Operations Plan at least six months before the expiration of the five-year site assessment period-that is, by the summer of 2018. BOEM will then evaluate the plan in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act, producing an Environmental Impact Statement in 18-24 months, before construction can begin. That timeline puts construction underway no later than 2020, with electricity from the first turbines flowing by 2022.

The process doesn’t have to take as long as this; Deepwater Wind, which won the two leases in the Rhode Island/Massachusetts area last month, says construction there “could begin as early as 2017, with commercial operations by 2018.”

But Dominion had previously indicated its preference for the slowest possible approach. The company’s original idea was to build some wind turbines, think about it for a while, and five years later start all over again. Then five years later, round three. Another five years, round four. So 20 years on, if Dominion liked what it saw each time, Virginia would finally have its 2,000 megawatts.

In accordance with this plan, Dominion’s surrogate, the Virginia government, asked BOEM to make the lease term for Virginia’s Wind Energy Area 45 years instead of 25.

Other developers and the environmental community cried foul, pointing out that such an approach would mean a generation would be born, grow up and go off to college before we had all our wind turbines-hardly the way to build an industry or stave off climate change.

BOEM conceded half a loaf and agreed to a 33-year term that allows time for a phased approach, but a faster one. The agency expects the construction plan will consist of four, two-year phases, ensuring completion of the build-out in 8 years-or by 2028, to be followed by 25 years of operation.

We can only hope that BOEM’s confidence is not misplaced. Dominion employees have said candidly that right now, under current market conditions, the company has no intention of actually building offshore wind turbines.

What will it take to change its mind? The company talks about costs and the difficulty of getting approval from Virginia regulators. It seems likely that the company will follow through with construction only if some combination of events happens in the next few years:

*Continuing advancements in technology bring the cost of offshore wind energy down. Already the latest cost estimates put offshore wind power well below the sky-high figures Dominion cites.

*Congress or the EPA tackles climate change through incentives for renewable energy (or disincentives for fossil fuels);

*The Virginia government passes legislation to create a market in Virginia for offshore wind power;

*Virginia’s State Corporation Commission (SCC), which regulates utilities, alters the way it views renewable energy.

Of these contingencies, the last might be the hardest. The SCC seems to believe the public interest is served only by providing the cheapest possible electricity available today. It shows no interest in climate change, or the pollution costs of fossil fuels, or long-term price stability, or job creation, or asthma rates. Ignoring the actual language of the Virginia Code, it declared this summer that Virginia law doesn’t require it to consider the environment in evaluating a new electric generation facility.

But the offshore wind industry is now off and running in the U.S., and the only question is whether Virginia wants to be part of it. On that answer depend thousands of jobs for our residents, an abundant source of stably-priced energy, and Virginia’s ability to move beyond fossil fuels in the face of climate change.

Virginians overwhelmingly want to move forward on offshore wind; now our challenge will be to make it happen.

![Sunday News: “Trump Is Briefed on Options for Striking Iran as Protests Continue”; “Trump and Vance Are Fanning the Flames. Again”; “Shooting death of [Renee Good] matters to all of us”; “Fascism or freedom? The choice is yours”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/montage011126.jpg)

![VA DEQ: “pollution from data centers currently makes up a very small but growing percentage of the [NoVA] region’s most harmful air emissions, including CO, NOx and PM2.5”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/noxdatacenters.jpg)