“Our lesson is, that there are two Richmonds.” – Charles Dickens.

On December 8, 2018, Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney led a march of more than a thousand people on the state Capitol to call for more funding for education. “Each and every day, there is a young man or a young woman who wakes up with a dream, and it is our job — as elected officials, as teachers, all working together — to give them the legs to stand on to achieve that dream,” Stoney said.

On June 19, 2017, Richmond Times-Dispatch reporter K. Burnell Evans published a horrifying exposé on a city elementary school. She reported that “teachers begin their days by wiping rodent droppings from students’ desks, said Ingrid DeRoo, the George Mason [Elementary School] site coordinator for Communities in Schools of Richmond. ‘Some teachers wear breathing masks all day in order to teach,’ DeRoo said of the air quality in what is widely acknowledged to be the district’s worst school building among dozens in need of major repairs.” Mason opened ninety-five years ago and was last renovated when Jimmy Carter was president. The scandal fomented a fierce response: parents and teachers donned surgical masks in public meetings; politicians pledged to do better; a petition to fix the problem collected 14,000 signatures in a city of 230,000; and reporters wrote dozens of follow-up pieces in the city’s other news outlets.

The School Board called a public meeting to hear citizens’ concerns. They responded with a litany of severe problems: “extreme hot and cold conditions, leaking bathrooms, falling tiles and infestations of bugs and rodents in their classrooms. A teacher said she regularly has to rescue children trapped in bathrooms, due to the failure of old doorknobs.” “My son has been sick 10 times in a row, and I can’t afford to miss work,” a parent of two children at Mason said. Fourth-grade teacher Hope Talley told the Board: “Our parents want what’s best for their kids, just like any other parent. They speak [their fears] to us, we hear them, and we have to explain why their child had to do without heat today.” “From 2006 to 2017, I’ve cleaned up rat poop every morning before my kids come in,” she told a reporter. “Every. Day.” “I cannot stress to you enough that the building of George Mason is in a state of emergency,” DeRoo said. “It is unsafe, unsanitary and harmful to our students and staff.”

Interim Superintendent Tommy Kranz noted that the “building leaks like a sieve.” He acknowledged to Evans that every couple of months, the smell of natural gas became so overwhelming that “the fire department and city officials respond.” On the other hand, he maintained the school was safe, and stated that “if I wouldn’t send my grandchildren into a building, I’m sure not going to send anyone else’s child.” (Two years earlier, Kranz had sung a different tune, saying that the slightly better but still inferior Overby-Sheppard Elementary School “isn’t one we should have our children in.”) He proposed options for Mason with costs ranging from $105,000 to $10 million; building a new school would cost “between $22 million and $35 million,” and would take years to complete. The School Board meeting adjourned without action, guaranteeing that the elementary would remain “a place where children will still confront the acrid smell of urine.” It was reported that “the crowd proceeded to chant ‘our children deserve better’ as they left the hearing.”

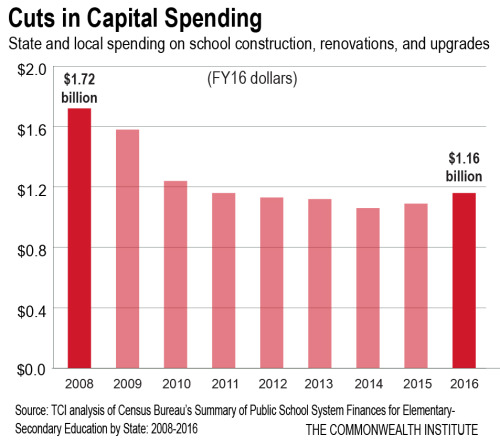

It was no surprise when the Board voted two weeks later to fund the absolute lowest option presented, for $105,000. To some extent, the Board’s hands were tied, as overall tax and budget levels were set by the Mayor and City Council. School Board Chairwoman Dawn Page noted that they had “facilities plans for all schools dating back 20 years, but with no funding, the plans cannot be executed.” In the most recent example, after the Board experienced a 100% turnover after the 2016 elections – not a single member was reelected, though two successfully ran for City Council – the new members requested $207.4 million for “school buildings needs” and received less than 4% of their request from City Council.

Many residents felt that Richmond government had plenty of money to address these issues. “We’re not lacking in money, y’all, we’re lacking in moral commitment,” said former Councilman Marty Jewell. Richmond protected its bond rating by assiduously maintaining a “self-imposed,” arbitrary debt level. Even within this constriction, the city had “about $8.5 million in [bond] capacity through 2021, and about $321 million combined between 2022 and 2026. Richmonders frequently pointed out that city government had built the Washington Redskins a $10 million training camp and paid them a $500,000 annual subsidy, based on lofty promises that never materialized, just as experts predicted they would not. The Richmond Times-Dispatch published “a photograph of a decrepit boys’ bathroom at the city’s George Mason Elementary school, last renovated 37 years ago, showing two of four urinals in working order and only one operational sink.”

The editorial board angrily wrote:

“Whatever publicity Richmond might be getting out of the [Redskins] deal can’t begin to stack up against the need to improve Richmond’s schools. Fixing them would do more for the city than any sports or entertainment offering possibly could. As any real estate agent will tell you, schools are the top concern for most people who are looking to relocate. They’re the main reason young families move out of Richmond to the counties, and a major reason families from the counties don’t move into the city. Nobody from outside the area is ever going to look at the city and say: ‘I’m going to move to Richmond. My kid will have to sweep rat droppings off his desk at school and his teachers will have to wear surgical masks because the air is so bad, but at least I won’t have to drive far to watch [quarterback] Kirk Cousins run drills.’”

While the recriminations continued, another school year started with little to distinguish it from the prior one. A group of about a hundred people, including teenagers from Henrico High School, volunteered to apply some fresh paint to the hallways before Mason opened its doors for the fall. On the day of volunteer action, “hot water would not turn on and the bathroom door would not lock on the bathroom at the school’s main entrance.” “The rest of these fixes are nothing but expensive Band-Aids for problems that we shouldn’t be continuing to have,” said teacher Hope Talley. “I hate the expression, ‘Lipstick on a pig,’ but that’s all I can think of,” said another teacher. Three weeks after the school reopened for the fall, water there tested high for lead, and the school had to begin “providing bottled water to students, faculty and staff.”

Why Are Richmond’s Schools the Worst in the State?

The reason nothing changed was clear. “We have resegregated schools that are underfunded and get blamed for the deliberate segregation that has been imposed on them,” said Ben Campbell, author of Richmond’s Unhealed History, one of the two greatest books ever written about Richmond. “The General Assembly isolated the City of Richmond and made it economically nonviable in the middle of three affluent suburban counties that were created for the purposes of racial segregation.” Many of Virginia’s ‘great men’ had dedicated the bulk of their careers in the mid-twentieth century to committing one of history’s greatest crimes by shutting down public schools rather than having black and white children attend them together. This state policy violated the Brown decisions, and federal district court Judge Robert Merhidge nearly compelled Richmond to annex much of the adjoining suburban counties, as many comparable cities from Charlotte to Chattanooga to Louisville had done voluntarily. Richmond could have avoided so many of its problems if this ruling was not enjoined by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, and then upheld by a 4-4 U.S. Supreme Court decision that Justice Lewis Powell, who had served on the Richmond School Board, recused himself from. Richmond really had, in a grotesque sense, “a perfect school system,” said a local nonprofit leader, “because it was designed to give children of color an inferior education and put them in inferior buildings and teach them as little as possible, and that’s exactly what we do everyday.”

There were two Richmonds, wrote Michael Paul Williams, “one ascendant, the other mired in violence and decay… George Mason and much of the [public] housing stock are remnants of an era we never truly left behind. Even as [other] neighborhoods gentrify and industrial areas such as Scott’s Addition and Manchester morph into eclectic residential communities, Richmond’s public housing and school buildings remain largely frozen in time.”

The Crusader with a Conscience

Democratic strategist Paul Goldman had been beating a drum for years about the shameful state of Richmond’s public schools. Goldman had the rarest of gifts in politics: a sincere, relentless idealism. “Goldman never wanted office,” Dwayne Yancey wrote in When Hell Froze Over.

“If he did, maybe the establishment could understand him better, and maybe it could have bought him off long ago, dispatching him to some far-flung do-gooder office where he’d be out of the way. Nor was Goldman interested in money. If so, he could have cashed in long ago as a political consultant. In a jungle full of mercenaries, Goldman is more of a missionary, a crusading zealot in the game for a higher purpose. He only signs on with candidates he believes in, then pushes their cause with a single-minded fanaticism as unnerving as his ragtag personal style.”

In 2017, Goldman had an unused ace up his sleeve in the power of public opinion. Where top-down reform had not worked, perhaps the will of the voters could in the form of a citizen referendum. Goldman had the wherewithal to do it, having led a successful 2003 petition drive to allow Richmond citizens to popularly elect their mayor (critics noted that his friend Doug Wilder was the first beneficiary of this legislative change). He would launch a petition drive to put the issue before the voters, and ask simply that the Mayor either come up with a plan to fully fund school modernization within six months without tax increases, or else say it could not be done. The first coverage of Goldman’s plan was in an article by K. Burnell Evans on June 5, 2017 – two weeks before her exposé of the rat feces and surgical masks of George Mason Elementary School, and three weeks before Farrell’s Coliseum pitch. “This is not aimed at anybody,” Goldman said. “This is about the needs of children who attend inadequate schools.”

Richmond’s political structure did not feel that way. It was no exaggeration to say that its members responded with uniform antagonism to try to stop the initiative from passing, and even from appearing on the ballot. If Richmond was a society where politicians reflected the will of their voters, then Paul Goldman would have received a key to the city. Instead, he was targeted with dismissal, whispering, ridicule, and personal and political attacks of every sort.

On November 7, 2017, Richmond voters thwarted the will of their Mayor and nearly every other person of power in the city to deliver 85.4% support to the referendum, with landslides in every council district and precinct – black, white, rich, poor, young, old, everywhere. “Eighty-five percent is about as close as you can get to unanimity in the political system,” said Goldman. “The people have spoken and sent a message to city leadership.” Yet not a single Democratic politician supported it in an overwhelmingly Democratic city. “Nothing,” said Goldman. “Baffling, really, since I was trying to get them money for their constituents and they still wouldn’t do anything.”

Field of Schemes

It was as if a parallel universe existed in the other Richmond, where “a shadow government of big business chieftains, lawyers, bankers and planners relentlessly tries to push things its way.” At the same time that school emergencies were banner news, the other Richmond sought to hamstring the city’s ability to finance school construction for the next generation by earmarking public money for private pockets. Just eight days after Evans’ bombshell article on Richmond’s dilapidated schools, Dominion CEO Tom Farrell announced he would spearhead a $1,400,000,000 urban renewal proposal for the Richmond Coliseum. As news of the latter emerged, its inconsistencies quickly began to pile up into a shaky house of cards that revealed the true intent.

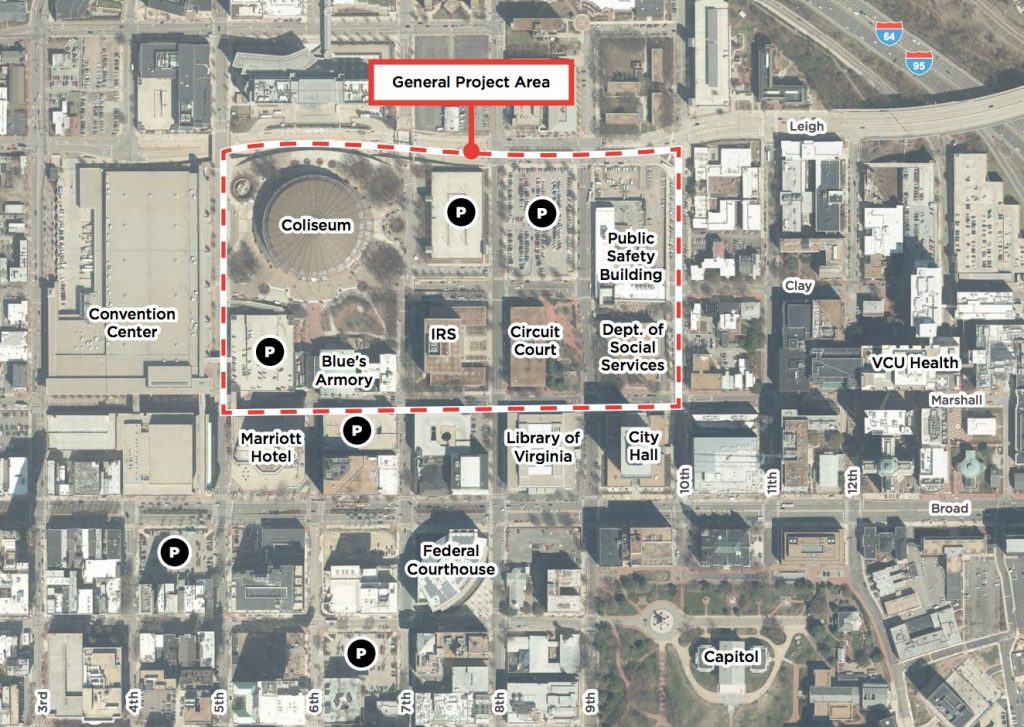

The details of the proposal were vague and kept out of public view. They were negotiated behind closed doors between Stoney’s office and what was often euphemistically referred to as ‘the business community,’ essentially one or two dozen Republican CEOs of Richmond companies. The same people were always behind ostensibly civic projects that had been pushed for decades, usually to the detriment of the public coffers. The Coliseum proposal reconstituted the business-political alliance that had led to boondoggles such as the Redskins deal. In the most recent iteration, it shifted the location of a proposed public-private megaproject from the Boulevard and Shockoe Bottom areas to the Richmond Coliseum and replaced Mayor Jones with Mayor Stoney. Dominion’s other lead on the project besides Farrell was Jones’ former chief of staff, Grant Neely. The lynchpin was replacing the Coliseum – which was built in 1971 and hardly ever hosted events – with a larger arena, which would be financially successful for some unstated reason. The arena would be joined with a new hotel and apartment building that would replace a federal building, the city courts, a few parking lots, and two buildings hosting a variety of city functions such as social service and job agencies.

Jeremy Lazarus of the Richmond Free Press pointed out that these facilities would have to move somewhere, but during the first year and a half the proposal was under discussion, it was not mentioned by a single person where those federal and city offices would move. Only in late 2018 did it begin to come out that the social services building would reportedly move to an out-of-the-way former Altria operations center with sporadic bus service six miles down I-95. The entire project would be funded by tax increment financing, whereby any tax revenue collected from an area above current revenue levels would support bonds to pay for the construction. Of course, inflation alone would naturally double the value of this area over thirty years.

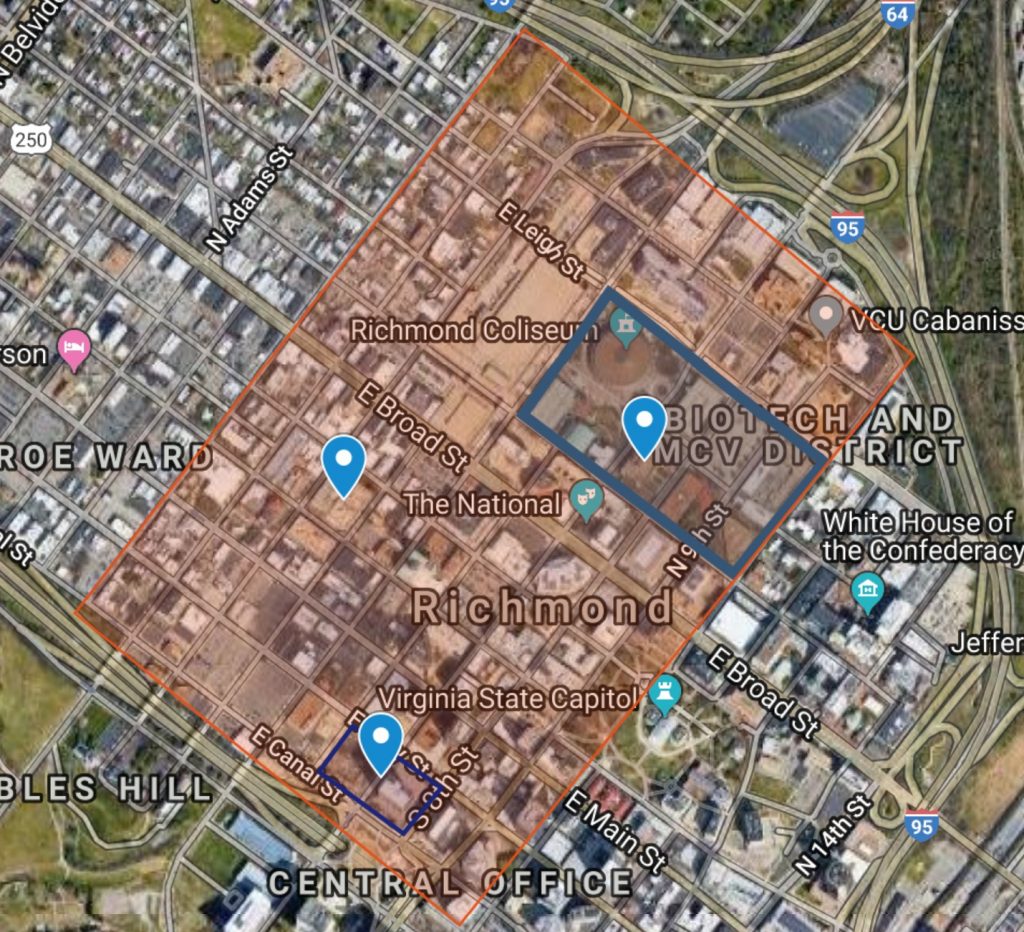

This precise area had been the focus of at least four big-ticket urban renewal projects over the past sixty years, about once every fifteen years as if on schedule. Richmond had a relatively small budget and strict debt limits that were lavishly tapped four times for these projects, and which failed four times in a row. The original sin was to bulldoze the prosperous area of town known as “Black Wall Street” to build the I-95/64 highway in the north corner of the map. That destroyed and hollowed out the neighborhood. Secondly, the unsightly Richmond Coliseum was built in 1971 with $16 million in taxpayer funds; it had since received millions more in public subsidies, including $7.1 million in renovations in 2003. In the 1980s, the Sixth Street Marketplace at Sixth and Broad cost more than $30 million in city bonds and opened to much fanfare; retail tenants in the Blues Armory slowly left when customers failed to materialize. The frontispiece was a pedestrian bridge crossing Broad; the bridge and much that remained of the project was razed at the cost of an additional $800,000 in 2003. The Convention Center cost more than $170 million in city and country funds in the early the 2000s. Its backers, too, had promised that construction would develop what was now suddenly in need of redevelopment. “Time after time the city commissions some consultant, many of whom I know and respect, to provide gaudy numbers on how one project or another will pay back the taxpayers, but none of these publicly funded land deals ever end up working the way they were sold,” concluded School Board member Jonathan Young.

The area slated for renewal was adjacent to the expanding VCU Medical Center, and it was striking to see what could only be described as willful amnesia amongst ‘the business community’ about what had taken place within the last few years. The cornerstone of Mayor Jones’ Boulevard redevelopment project was building a children’s hospital with the help of a generous $150 million pledge from local philanthropist Bill Goodwin. One of VCU’s main objections was that the Boulevard was five miles away from the medical campus that hosted hospitals, clinics, offices, and dental, medical, nursing, and allied health schools, and would thus warrant inefficient duplication of many facilities and services. None of this happened in a minor footnote somewhere: an entire forest probably gave its life for all the press coverage of that unsuccessful idea, and Goodwin himself was a member of the Coliseum group. Now, all of a sudden, the very parcels not available to VCU to build a pediatric hospital because they housed critical government services were suddenly free for the taking if Hyatt would build a hotel there with the help of public funds.

Furthermore, the area was not some ghost town that nobody visited, and it was astonishing to hear it repeated again and again that the area was some variation of an “urban wasteland,” as the Richmond Times-Dispatch editorial board opined. The board had seemingly forgotten its prior take on sports arenas, which it had lambasted for costing the city perhaps $15 million. “Whatever publicity Richmond might be getting out of the [Redskins] deal can’t begin to stack up against the need to improve Richmond’s schools,” its members had written. “Fixing them would do more for the city than any sports or entertainment offering possibly could.” “In a city that claimed to worship history,” the most important truths were unmentioned because of Richmond’s cognitive dissonance about plain facts; the area north of Broad Street had been historically black, and south historically white. There was still some of that segregation today, especially in housing, but the VCU Health campus and surrounding government areas were probably the most integrated and accessible places in the entire city: everyone got sick or had to go to court or City Hall at some point, after all. There were plenty of people in the area slated for ‘redevelopment:’ Richmond was a majority black city, and maybe two-thirds of the people in this area at any time happened to be African-American residents just living their lives.

Yet Richmond’s Chamber of Commerce leaders penned their feelings about it in Richmond’s inimitable coded language: “Do we want the space between the VCU Medical Center and the convention center to become a walkable, attractive area filled with residents and visitors or do we prefer blocks of unattractive old office buildings that encourage folks to stay away?” “Folks” did not “stay away:” even in the map above that the city submitted in its request for proposals, one can see hundreds of cars in mostly full parking lots. Thousands of people worked and conducted business there everyday, despite the Chamber leaders’ evident fear to even walk in the area.

Ben Campbell noted the conspicuous factor in the psychology of many Richmonders:

“We had a study about twenty years ago where the Chamber of Commerce went to Richmond’s peer cities in the mid-Atlantic – Memphis, Charlotte, Greensboro, High Point – and found that of the cities they studied, Richmond had the lowest crime rate and the highest fear of crime. This is just me, growing up in Virginia, but I think that if you are busy keeping other people down and making a lie of the values that you state, that basically you are afraid of them, because you know that the people you are harming want to get you, or you think you know they might want to get you. If you read the stories of Richmond, there is constant fear of black people.“

There were two projects in recent years showing perhaps the most important motive for the project. Kanawha Plaza in downtown Richmond was closed for much of 2015 and 2016. The supposed impetus was sprucing up the city like a Potemkin Village for the September 2015 UCI Bike Championships, but the Plaza was a longtime encampment for the homeless, and it was closed during the race. In August 2015, a representative from Enrichmond, another group representing the same ‘business community,’ pledged to City Council that an unnamed group of private backers would provide $6 million to bulldoze and rebuild Kanawha Plaza. He asserted, falsely, in response to a question from Councilman Parker Agelasto, that the names of these backers had to be revealed in the nonprofit’s annual 990 tax forms. That never happened, of course, because that money was never there, and that information was not and could not be publicly disclosed in 990 forms. The financial backers of the Coliseum project have also not been revealed, if they even exist.

After the Plaza was bulldozed, the phantom backers withdrew their commitment and left city taxpayers on the hook for reconstruction. It was re-engineered as an anti-homeless park: it looked mostly the same, but structures like a pedestrian bridge and trees were destroyed. Areas where poor people would congregate were redesigned to prohibit sitting, and embankments were studded with metal plates so that people could not lie down. From 2016-2018, the target of urban renewal was Monroe Park, where homeless people also gathered, and its makeover bore the same hallmarks. It was closed for a couple years and the city threw a lot of money at it to make some cosmetic changes. Monroe Park had been imperfect but functional, and $6.8 million in renovations was a great deal of money: the budget for Richmond’s homeless services that year was about half a million dollars. The renovations also removed most of the park’s benches and added a police substation. When the park reopened, the homeless had disappeared.

Rather than inventing urban renewal projects to wipe out the homeless, it would have been cheaper to invest in decent services and public schools to prevent the perpetuation of desperate poverty. There were a handful of homeless people who lived in the Coliseum area, and the city’s cold-weather homeless shelter was in the Public Safety Building. The city began looking for a new cold-weather shelter away from downtown in late 2018. “Regardless of the benefits of having a centralized downtown facility to serve the homeless, Dominion’s Tom Farrell and the City want it out of the way,” wrote developer Michael Hild. “It is a poor solution at best,” he continued. “The City is attempting to turn its back on the issue and push the downtrodden across the river, and hoping no one will notice. Leader’s of other cities have been excoriated for giving the homeless bus tickets and moving them out of town before sporting events such as the Super Bowl or World Cup. This sure feels awfully similar” [sic]. It was not like spending all this money actually solved the problem: it merely displaced one or two dozen people so businessmen would not have to look out their windows at them.

There was indeed a problem with the outdated Coliseum and its $1.75 million annual subsidy from the city, but that could be solved by selling it on the free market. The city valued the parcel at $12.3 million. Lazarus and Style Weekly’s Jackie Kruszewski convincingly argued that it was not clear if there was a good reason for the Coliseum even to exist. Instead, the captains of industry who usually sang hosannas to capitalism wanted to distort it with cronyism, just as they and their forebears had mismanaged development of the area for decades. Farrell had used public money to make what one reviewer called a “contemptuous” Confederate movie in which Lincoln and Grant conspire to murder children. Farrell was a member of the Gray family, whose patriarch had sat on the Dominion board and who bore as much responsibility as any Virginians for massive resistance. It was difficult to maintain with a straight face that the four-block Coliseum parcel would suddenly become filled with more people during the day if it were replaced with a larger arena that would also necessarily hold events only at night or on weekends. “It comes up in every meeting: this can take Beyoncé,” said the investment group’s spokesperson, Jeff Kelley. The indelible image for the schools crisis was teachers wearing surgical masks to teach in Richmond’s true “urban wastelands;” here, the indelible image was a group of old men behind closed doors stoking each other’s egos and repeating, ‘if we build it, she will come.’

Stoney kept mum about his plans for the proposal while he very openly opposed Paul Goldman’s school referendum. An October 2017 poll showed that 64 percent of Richmonders supported paying more in taxes for schools, while 65 percent were opposed to using public money on the Coliseum project. Amazingly, just two days after the 2017 elections and referendum, Stoney held a press conference to announce “his” request for proposal (RFP) on a development project that was nearly identical to the one proposed by ‘the business community.’ “I am well aware of their ideas,” Stoney said, “but this is a city of Richmond project.” The RFP differed little from Farrell’s proposal except to call for a rebuilt bus transfer station and affordable housing as part of the new apartment complex. “I prefer competition,” Stoney said. The extent of the competition was clear when the RFP closed in February and only one group submitted a proposal: the same group that had initiated the RFP.

“Our city made it clear that our priority should be our schools, and I agree,” School Board member Kenya Gibson said wistfully.

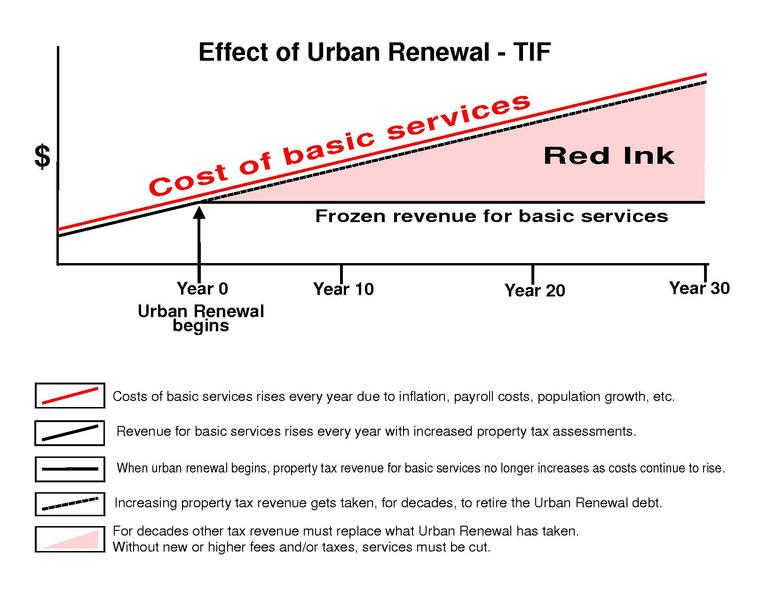

The financial numbers behind the proposal were impossible to believe. Tax increment financing was itself a disingenuous ploy. Any real estate in downtown Richmond would appreciate over the course of thirty years; earmarking this revenue towards a bond proposal would starve the city of resources and was no different than raising taxes by any other means.

A new arena would cost around $220 million and “over 30 years would require an annual payment of $11 million to $22 million a year, depending on the interest rate;” the taxes on such an arena would amount to just $2.4 million yearly. “Several developers the [Richmond Free Press] consulted and who spoke on condition of anonymity could not fathom how a private coliseum could generate enough income to cover debt, let alone generate a return on the investment,” Lazarus wrote. The bottom line for the new project began at $1 billion in total investment, but, as time went on, that grew to $1.4 billion, and the money that the public would put up went to $300 million, or $620 million with interest, nearly the cost of completely modernizing all of the city’s schools. The proposal took time and money from such efforts: by September 2018, the city was canceling scheduled events at the arena and had spent nearly half a million dollars just reviewing the single proposal. “I can’t wrap my mind around half a million dollars for studying a Coliseum deal that we haven’t even had a public conversation about as council,” Councilwoman Gray said.

City Council and the public continued to be kept in the dark about any details, but the public got the best look at the cronyism and unstable financing of the proposal in documents uncovered by reporter Mark Robinson. The project would now be funded by tax increment financing as well as the taxes from Dominion’s downtown office buildings, which were so far away from the project that they do not even appear on the above map. Farrell “said it’s just a coincidence that Dominion’s new tower is part of the proposal.” He must not have checked with his public relations team, because spokesperson Jeff Neely claimed in another article that “it’s the closest taxable property to this area.” This was patently false: there were dozens of taxable properties from small and large businesses to apartment buildings to hotels that were closer. “If that is the proposal, that would not be palatable for me,” said City Council President Chris Hilbert, who deemed it “troubling.”

As tenuous as those numbers were, they seemed almost reasonable compared to other aspects of the deal. The purported projections for arena revenue seemed to be invented out of whole cloth. The group claimed that it would “generate $3.7 million in revenue to help cover debt service payments in its first year in operation, and $5.8 million by its third year.” However, the “nine comparable arenas” that the group cited “made an average of $953,000 annually. The highest grossing venue brought in $2.9 million.” The group also claimed that meals tax revenue from new restaurants in the area would not displace meals tax revenue from other restaurants because, they absurdly claimed, the only people who would eat in the area would be new tourists and new residents. Esson Miller, the former staff director of the Virginia Senate Finance Committee, wrote that the businessmen were “rummaging through the city’s fiscal well-being, putting it at severe risk that could have long-term detrimental impact.” Analyst Justin Griffin found that the modeling assumed that every attendee at a Coliseum event would spend an average of $458.48 on popcorn, candy, and so forth. The capstone of the deal called for transferring these properties to the investment group for 99 years, a giveaway usually seen only in kleptocracies. Farrell had pledged that he would not see any money from the project; the electricity for the new businesses and residents would be provided by Dominion. Stoney, who well knew about the damning details that demonstrated the project was not on solid financial footing, was left in a bind and discarded his usual careful rhetoric. “This is our project,” he said. “This is not Dominion’s project. It’s not any other entity’s project. This is our project. This is my vision. … I don’t care if it’s Tom Farrell or Johnny on the street, if it does not benefit my city, this project will not move forward.”

The fantastic veered into propaganda at the headline claim Stoney repeated like a chorus that this would somehow create 9,000 permanent jobs. A $1.4 billion investment spread over thirty years worked out to about $47 million per year, or about $5,100 per year for every “permanent job.” Furthermore, most of the cost of the project would be spent on material, not labor. To give an example that backers should have been familiar with, Dominion Energy employed about 16,000 people and had about $12.6 billion in revenue annually. It was a 100% certainty that this project could not possibly create 9,000 permanent jobs and might actually increase unemployment through hiring less teachers, firefighters, and cops.

Imitation and Flattery

Stoney was a Clintonian public figure, in the best and worst senses of the word, though his personal life was far less tarnished. The conclusion of this story so often in Richmond’s history was that the people who owned the city’s private resources also controlled its public purse strings. Smart money was on ‘the business community’ co-opting yet another politician, but Stoney was seemingly not as malleable as his predecessor. In August 2018, Stoney called a reporter to tell him that Farrell’s proposal was not yet living up to his goals on affordable housing, and briefly stalled the negotiations. The trepidation that his designs on higher office would cause him to ignore the city may have been misplaced; the fact that he would need a base of voters for the future could instead serve as a corrective. Stoney was barely elected; Mayor Jones had pursued the same policies Stoney was pursuing and left office with the popularity level of Richard Nixon. There was one reality that proved more indelible than schoolteachers’ masks, grandees’ Beyoncé fantasies, or any opinion poll or political theory, and that was that 85% of Richmond voters wanted him to fix the schools.

Goldman himself had four aces, and he knew it. In mid-October 2018, he announced that he would pursue a second ballot initiative, “Choosing Children over Costly Coliseums,” that would require that 51% of money from any tax incremental financing in the city would go towards modernizing schools. He had nine months to collect signatures: nine months to let the inevitable landslide vote sit like a sword of Damocles over the Mayor’s political future. “Levar Stoney should have known better than to play political chess with a grandmaster like Paul Goldman,” Style Weekly concluded.

Stoney penned an extraordinary article in late October 2018, not for his adopted city, but for his hometown. “Many of our school buildings are well beyond their lifespan and are literally crumbling,” he wrote in the Virginian-Pilot. “They are no longer the safe, healthy environments our students need to thrive. But these facilities are just one part of the education crisis facing us today – our entire K-12 education system is woefully underfunded… Failing to provide for the most vulnerable among us today is not just unacceptable, it is immoral.” He called on Virginians to join him in marching on the Capitol on December 8. Though pride and personality usually prevented most public figures from reversing course, political observers understood well the lengths to which this was an endorsement of Goldman’s cause.

On November 1, 2018, Stoney unveiled the program that he had kept under wraps during months of secret negotiations. It made a lie of all the financial promises about how ‘additional’ revenue would pay for the construction in the eight-block zone. The TIF district would be expanded from eight to eighty blocks encompassing essentially all of downtown Richmond and all of its office buildings between 1st and 10th Streets and I-95/64 and I-195. Under this program, the additional money that would be needed to pay for citizens’ schools, police, firefighters, snow removal, trash pickup, and all the other vital services that cities needed to function would for at least the next thirty years be earmarked to paying back private investors. Goldman’s referendum would mandate that 51% of any TIF revenue go to schools; under Stoney’s plan, only 50% of “surplus” revenue after bondholders had been paid back would go towards schools and public services. It took the most lucrative and stable revenue source for the city and turned it over to wealthy businesses for more than a generation.

So far as can be determined, no city in the history of the United States has ever done such a thing. There is no precedent in Virginia since long before the Revolutionary War; one has to go back to the Virginia Company of London, when King James would simply decree that common land belonged to whomever he wanted. It was indescribable.

Richmond should not have had a double standard of miserliness or largesse depending on whether children wanted to attend healthy schools or businessmen wanted more money. Furthermore, there was just as much construction money to be made from building schools as there was from building an arena; the choice to pick one over the other was a moral judgment.

Robert Caro wrote:

“Although the cliché says that power always corrupts, what is seldom said, but what is equally true, is that power always reveals. When a man is climbing, trying to persuade others to give him power, concealment is necessary: to hide traits that might make others reluctant to give him power, to hide also what he wants to do with that power; if men recognized the traits or realized the aims, they might refuse to give him what he wants. But as a man obtains more power, camouflage is less necessary. The curtain begins to rise. The revealing begins.”

Though the public was clear on its priorities, it seemed sometimes as if Mayor Stoney, the humble kid and ambitious pol, was torn between the two Richmonds. It seemed that way, that is, until one saw that Stoney just did whatever his donors wanted, even if it meant realizing the wildest dreams of the supporters of massive resistance by helping them annex the city’s financial district. ‘Choosing children over costly coliseums’ required the tripartite realization that it was the right thing to do, was good politics, and that blind fealty to the Virginia Way was a lost cause.

***

Jeff Thomas is the author of Virginia Politics & Government in a New Century: The Price of Power.

![[UPDATED 1/6/26] Several Upcoming Virginia Special Elections in January – for SD15, HD77, HD11, HD23, HD17; Also a Dem “Firehouse Primary” for Fairfax County School Board (Braddock District)](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/montagespecialelections010226.jpg)

![Virginia NAACP: “This latest witch hunt [by the Trump administration] against [GMU] President Washington is a blatant attempt to intimidate those who champion diversity.”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/gmuwwashington.jpg)