From The Commonwealth Institute:

In the last two months, Virginia families and businesses across the commonwealth have taken the extraordinary step to stay home and shut down commerce in order to protect public health and keep each other safe. This necessary step has, as expected, resulted in the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs. Unfortunately, due to economic disruptions these job losses are likely to last far beyond the immediate public health emergency. Initial data from the Virginia Employment Commission shows just how far-reaching the job losses already were by late April, and the reality that working people of color may be experiencing even greater job losses than white working people.This is, unfortunately, not surprising given the lessons of the Great Recession, when unemployment rates rose for Black, Latinx, and Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Virginians well above the average statewide levels due to the lasting impact of past public policy choices that made some communities more vulnerable to job loss.

Unfortunately, we know from the early data that is available and the lessons of the Great Recession that despite many workers of color being employed in essential industries in Virginia, families and communities of color who are already facing barriers to economic opportunity are likely to be hit hardest by layoffs. Policy choices at the federal level about how to structure the recent relief efforts are likely to increase the problems. By making thoughtful choices that prioritize the needs of low-income communities of color that are most likely to face job losses and have the least ability to stay afloat due to existing and historical structural barriers to opportunity, Virginia’s state and local policymakers can protect Virginia families while setting the stage for a more equitable economy of the future.

Early Data About This Recession

That hundreds of thousands of Virginians are suddenly out of work has been well covered in the press. Between March 15 and May 2, 625,610 people applied for unemployment insurance in Virginia despite reports of many would-be applicants being locked out by technical issues or language barriers accessing the unemployment insurance system. This is almost 1 in every 7 people who was working in Virginia in February and is an unprecedented level of unemployment insurance claims in just seven weeks. The 625,610 initial unemployment claims during the seven weeks ending May 2 was almost 5 times greater than the highest prior seven week period on record, which was December 1990 through February 1991. (The expanded unemployment insurance provisions under the federal CARES Act allow more out-of-work Virginians to access unemployment insurance than during past recessions, which may account for some of the difference in initial claims compared to past recessions.)

The Virginia Employment Commission releases data about the demographics, industry, and city or county of employment for new unemployment claimants. Additionally, the federal Department of Labor provides cross-state summaries of the demographics of unemployment insurance claimants by month. As expected, the highest number and rate of unemployment insurance claims in Virginia have been in the accommodations and food services industry, with over 96,000 new or continued unemployment insurance claims during the week ending May 2, which is more than 1 claim for every 4 jobs that existed in that industry in Virginia in spring 2019. The smaller arts, entertainment, and recreation sector has also been hard-hit, with more than 1 claim for every 5 jobs that existed in spring 2019. And although a smaller share of spring 2019 employment, both the “health care and social assistance” and retail trade industries had more than 55,000 initial or continued unemployment insurance claims in the week ending May 2.

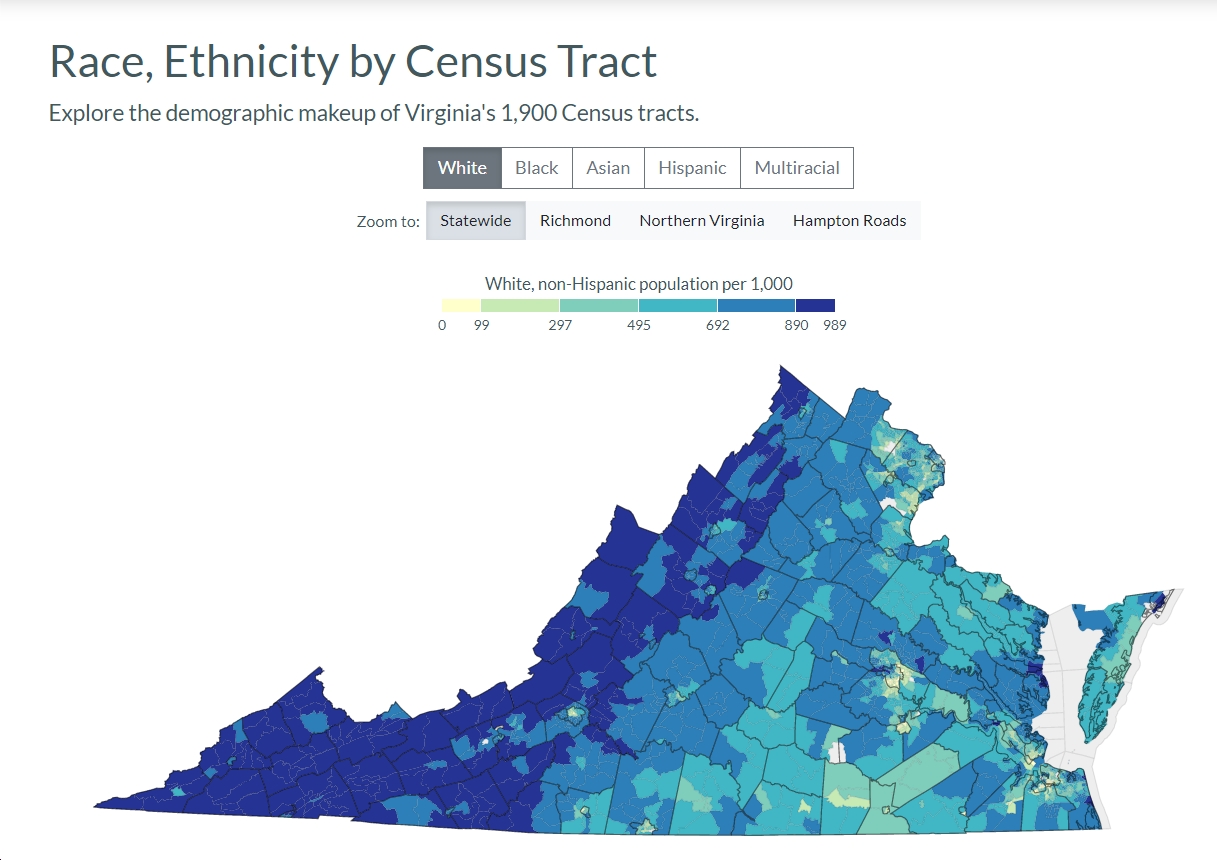

Similarly, the number of unemployment insurance continued and initial claims is not evenly distributed across Virginia. While the most claims in terms of total number are from Virginia’s largest cities and counties, some of the highest rate of claims as a share of the labor force as of spring 2019 are outside of the major metropolitan areas of Virginia.

(Click the image below for an interactive map showing UI claims, as percentages of the overall labor force, in localities across Virginia.)

The initial VEC data also shows that Black and AAPI workers appear to be more likely than white Virginia workers to have filed an unemployment insurance claim in recent weeks, indicating that these workers of color may have been more likely than white workers to lose their jobs in recent weeks. Last year, 18.5% of Virginia workers were Black, yet 24.5% of workers who have filed unemployment claims in Virginia in the four weeks ending April 25 are Black. When looking just at the share of workers whose race is recorded in the VEC dataset, the share who are Black jumps to 26.7%. AAPI Virginians were 7.4% of Virginia’s labor force in 2019, yet 11.4% of Virginians who have claimed unemployment insurance in the four weeks ending April 25 (and 12.5% of workers whose race is known) are AAPI. Unfortunately, this is in line with what we would expect to see during a time of job loss given the experience of working people of color in Virginia during the Great Recession and national studies of job losses by race during recessions.

The current economic downturn, which is almost certainly already a major recession although not yet declared by the National Bureau of Economic Research for technical reasons, is unusual because it is beneficial for public health for people to be at home rather than at work. In many cases right now, it would be inappropriate for someone who is out of work to be seeking new employment, whether because they have underlying health conditions that put them at high risk for serious complications from COVD-19, they are caring for a child whose school or daycare is closed, or they expect to be rehired in their prior job when the public health crisis is abated. Therefore, when new unemployment data from the Bureau of Labor Statistic’s household survey comes out, many currently out-of-work people who have filed for unemployment insurance and are counted as unemployment insurance claimants will not be counted as officially unemployed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which requires someone to be available for work and actively looking for work. Nonetheless, both unemployment insurance claims and unemployment statistics can provide some information about who is being most impacted by job losses.

If even half of the Virginia workers who applied for unemployment insurance between mid-March and late April are officially counted as unemployed, Virginia’s unemployment rate was already over 9% in late April, higher than any month on record in Virginia. And job claims continue to be filed, in part due to continued job losses and in part due to prior challenges filing for unemployment.

Since the unemployment rate for Black Virginians in 2019 was already above the rate for all Virginians, the large number of Black Virginians who are newly out of work and making initial unemployment insurance claims means the current total unemployment rate for Black Virginians is likely even higher than for all Virginians. If half of Black Virginians who have applied for unemployment insurance in between mid-March and mid-April are counted as officially unemployed, and assuming the demographics of Virginia unemployment insurance claimants between March 15 and March 28 are similar to those in April, 13% of Black Virginians may have already been unemployed by the week of April 25. This extra-high jump in unemployment is in line with past experience — the unemployment rate for Black Virginians has been at least 1.5 times the average unemployment rate for all Virginians since 1979 (the first year that data is available), and is frequently close to 2 times the rate for all Virginians. (Due to data limitations, doing similar estimates for AAPI Virginians would be less reliable.)

These economic challenges come on top of the particular heavy impact of COVID-19 on Black and Latinx Virginians, many of whom rely on public transportation and, for those who are still employed, have jobs where teleworking is not possible. And at the same time, Black and Latinx families are generally less able to rely on savings or family help to stay afloat during times of job losses due to having less financial wealth, which in turn is tied to less access to intergenerational and housing wealth.

This is not due to chance or the failures of individual people. As a result of exclusionary housing and employment practices, racist violence against Black organizers, the systematic underfunding of education, and mass incarceration, Black Virginians have often been prevented from successfully organizing to raise their wages, competing for higher-paid “white” working-class jobs, or obtaining advanced educations to compete for professional jobs. In addition, Virginia policymakers and business leaders have effectively suppressed unionization in Virginia through laws and ideological campaigns, thereby preventing working people in Virginia from raising their wages or obtaining workplace protections through collective bargaining. This is not to say that no progress has been made over time and that no individual Black Virginians have been able to overcome these extra barriers, but far too often, Black Virginians and, Latinx Virginians have faced barriers to advancement and have been stuck in low-wage, precarious occupations with little job security, little ability to work from home, and little ability to gain better pay and save for a rainy day.

One data concern about the initial VEC demographics data is that very few unemployment insurance claimants in the VEC data are identified as Hispanic or an “other race,” despite 11.2% of Virginia’s labor force identifying as Hispanic or Latino in 2019. And the federal Department of Labor cross-state data, which is based on reports from state unemployment agencies such as VEC, shows that very few March 2020 unemployment insurance claimants are identified as Hispanic or Latino. By comparison, Virginia’s neighboring state of Maryland and North Carolina, where Latinx workers are a similar share of the labor force as in Virginia, report that 6.3% (Maryland) and 5% (North Carolina) of March unemployment insurance claimants identify as Hispanic or Latino. This apparent lack of reliable data for Hispanic and Latino Virginians is particularly troubling because national surveys indicate that Latinx workers are being hit hardest by job losses, and national data from mid-March indicates that unemployment rates were growing fastest for Latinx and AAPI workers.

Lessons from the Great Recession

During the last recession, the number of jobs in Virginia fell by 180,000, driving the unemployment rate up to 7.5% in 2010. Job recovery was a long process — it wasn’t until 2014 that Virginia had as many jobs as in 2007.

With job losses and rising unemployment came falling real wages for Virginians without a college degree, growing wage inequality, and a sharp increase in the share of Virginia families struggling to make ends meet, effects that lingered for many years. While some safety net programs responded to the growing needs of Virginia families, enrollment in Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) had actually fallen by 2013 compared to 2007.

Beyond the topline numbers, the experiences of Virginia families during the Great Recession can offer some hints as to what may happen during this recession. Past public policy choices that limited access to education, de facto occupational segregation, and ongoing discrimination mean that workers of color were even more likely than white Virginians to be unemployed. The unemployment rate for Black residents of Virginia rose to 11% in 2009 and stayed that high for two more years before gradually declining to 4.3% in 2019. An unemployment rate of 11% meant that for every eight Black Virginians who had a job, there was a ninth who was actively searching for work.

And it’s not only Black Virginians who saw particularly large jumps in unemployment during the Great Recession. The unemployment rates for Latinx Virginians and Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Virginians were above 8% in 2009, which was also higher than the average unemployment rate for all Virginians. Data is less available for Hispanic and AAPI Virginians than for white Virginians and Black Virginians, and is very limited for American Indians and multiracial Virginians, making it harder to predict how the current recession will impact non-Black people of color in Virginia, but available data point to troubling trends.

The economic setbacks from the Great Recession were long-lasting for Black and Latinx working people and families in Virginia. Ten years after the start of the recession, real wages for Black and Latinx workers were still down compared to 2007 levels, while real wages had increased slightly for white workers in Virginia. And the impact of higher unemployment rates and the evaporation of housing wealth due to discriminatory subprime lending and the bursting of the housing bubble meant that Black and Latinx families saw long-lasting drops in wealth during and after the Great Recession. Between 2005 and the depth of the Great Recession in 2009, the typical white family saw their wealth drop 16%, while the typical Black family saw their wealth drop 53% and the typical Latinx family saw their wealth drop by 66%. And even as typical net worth for white families held steady between 2010 and 2013, net worth for Black, Latinx, and other non-white families continued to fall. By 2016, the typical Black family had just 10 cents of wealth for every dollar held by the typical white family, lower than at the start of the 21st century. Unless local, state, and federal policymakers are careful to avoid repeating the same mistakes as during the last recession, the impact of the current recession could be even worse.

Conclusion

As Virginia policymakers consider how to respond to the current economic challenges and rebuild the economy, it will be critical to make sure that the state prioritizes the needs and voices of workers and families who face the greatest barriers and have been hardest hit by the current downturn. In the short term, this could include the following policies, which will be discussed in a subsequent blog post.

- Reduce the impact of loss of employer-provided health insurance due to job losses by expanding access to health coverage:

- Cover COVID-19 screening, testing, and treatment in Emergency Medicaid.

- Broaden access to Medicaid by removing the 40 quarters barrier and improve access to care within Medicaid by raising provider reimbursements and extending dental coverage to adults.

- Increase emergency and cash assistance for families who have lost jobs and may struggle to find new employment:

- Address gaps in state and federal assistance for families, particularly for immigrant workers who are left out of many federal programs.

- Continue to strengthen TANF cash assistance for very low income families who may not be able to find a job or face barriers to employment.

- Strengthen the Virginia unemployment compensation system so that it can better meet the state’s needs when federal improvements expire.

The economic impact of the COVID-19 public health emergency is already being deeply felt across Virginia and appears to be hitting hardest in communities of color that are less able to weather job losses through the use of savings. This is not by chance — there is a long history in Virginia of policymakers failing to act to protect working families and instead too often erecting barriers to success, particularly for working families of color. Working people and families of color in Virginia have worked hard to overcome these barriers and shift public policy — Virginia’s recent passage of a minimum wage increase is an example of the fruit of this work. Yet much more can and must be done, both to protect families in the short-term and rebuild the economy to create more equity and opportunity.

— Laura Goren, Research Director

For more information on addressing unemployment, attend TCI’s webinar, Unemployment Insurance: Recent Reforms & Opportunities To Build A Stronger System In Virginia, this Wednesday, May 13, from 1-2 p.m. Register at this link.

Print-friendly Version (pdf)

Learn more about The Commonwealth Institute at www.thecommonwealthinstitute.org

![[UPDATED: VA Senate Dems Pass $15/Hour Minimum Wage Bill] VA House Democrats Pass Top Priority, Paid Sick Leave](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/housedemspaidsick.jpg)

![Virginia NAACP: “This latest witch hunt [by the Trump administration] against [GMU] President Washington is a blatant attempt to intimidate those who champion diversity.”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/gmuwwashington.jpg)