I had a great conversation this weekend with Ramin Fatehi, who is running to replace his boss, outgoing Norfolk Commonwealth’s Attorney Greg Underwood. Norfolk prosecutors have often been in the news–first with the infamous 1997 conviction and subsequent exoneration of the “Norfolk Four” (who were convicted on false confessions made under intimidating interrogation); a similarly problematic 2004 conviction and death sentence of Anthony Juniper (witness interviews conflicted with the prosecution’s story and timeline–none of which was disclosed to the defense by the prosecutors); and most recently, when Underwood announced he would stop prosecuting simple marijuana possession and was thwarted by the court. Ramin and I talked at length (seriously, sorry for the length!) about how the Norfolk prosecutor’s office has become a leader on criminal justice reform, possibly in response to its terrible past history. – Cindy

First of all, tell me a little bit about your background, and what made you interested in criminal law?

I’ve had a very fortunate and a little bit unusual life. My father’s Iranian-American, my mother is White-American. They met here in the 1970s and moved back to Iran. I lived in Tehran until I was almost 7 years old. I went to my first year of elementary school there. It gave me an interesting perspective on things, both during the time I was in Tehran, and when we moved back to the States. I always had a foot in both worlds. In Iran, I had to take up for America and take up for my American mom, and when I moved to back to the States, I had to take up for Iran and for my Iranian dad, so you know it’s given me a sense of what it’s like to be both part of, and not quite part of, the world you’re living in.

As I said, my life has been very fortunate, growing up with all of the advantages in life, and having lived in Virginia Beach as child, having gone to Yale, and Columbia Law School, and then having moved back to Virginia and clerked for the Virginia Supreme Court after law school. I had always had an interest in criminal law–and really in prosecution–because of the work that my father and mother had done. My father recently retired as a surgeon, and my mother was a nurse by training and I remember as a child that my dad would take me on rounds. We’d go see his patients that he’d operated on, and he modelled devotion to serving other people and to doing the right thing; and while I decided to go into law, I took that same devotion into the work that I decided to do. One of the great advantages of being a prosecutor is that my client is justice. It’s the public interest. It’s ensuring that the fair thing happens, for victims, for people accused with crime, and for the public at large. Having worked as a public defender as my first criminal law job–which was immensely valuable and taught me the importance of prosecutors–I also recognized that the greatest way to do the greatest good was to be involved on the prosecution side, and that’s why for the last 14 years of my career I’ve been both a federal, and, for almost all of it, as a state prosecutor.

You were just a defense attorney for a year is that right?

Yes, on the criminal side. Following my clerkship, I worked at a large Washington firm for just under a year doing civil work, but then from there I went to the Richmond public defender’s office for a year which was in some ways the best experience of my career. I worked there, it was a flagship office, I learned a great deal about accused people as human beings, and learned to recognize that the vast majority of people who are charged with crimes are not bad people they’re good people who have made bad choices, or who have been left with only bad choices.

Can you explain just for the layman what exactly happened when the Norfolk Commonwealth’s Attorney’s office decided to stop prosecuting marijuana possession. What did the judges do, and what’s the status now of all of that?

We were really surprised by how things went in 2019. Starting in late 2018 Greg convened a criminal justice reform working group in our office and asked me to chair it shortly after the first of the year. The group was designed to pursue progressive policy ideas. We put out three policies, two of which wound up being pretty uncontroversial. One was eliminating our prosecutors’ discretion to request cash bail. We told everybody that if someone should be released, that they should be released without cash bail. We have another policy that lessened the penalties for individuals charged with prostitution, with obvious exceptions for individuals who’ve been trafficked.

The third one was the marijuana policy, and we looked at it and we put it into place once we realized that in the city, where we were really 50/50 white and African-American, that over the prior two years 80% of defendants charged with marijuana possession were African-Americans, and between 89 and 94 percent of second offenses were African-Americans. So we decided on the policy of blanket dismissal for possession. We walked into court essentially expecting this to be a routine matter, having publicized it with the intent of increasing community trust in letting the community know that we wanted to allocate our resources properly and to deal with this racially disparate outcome. And I got a frantic telephone call from a subordinate that a judge had refused to take one of our orders for dismissal. I went personally the following week to handle this as the head of the reform group, and as the author of the memorandum that described our policy. I ran into more roadblocks, and ran into a third set of roadblocks the following week in front of a third judge. Back channel communications indicated to us that all eight of our circuit judges were united in opposing our policy, and feelings that we had overstepped what the legislature allowed for us. We subsequently got information that perhaps it was not unanimous after all, but at that point the die was cast.

We weren’t obligated by law to prosecute marijuana misdemeanors. The Virginia Code says the Commonwealth’s attorneys are only required to prosecute felonies, but we were really worried about the precedent the judges were setting in saying that we didn’t have the right to dismiss cases. So we decided to take our judges to the Virginia Supreme Court, and to file what in legalese is called a petition for a mandamus–something essentially to order judges to follow the law where they lack discretion. Prior to the Virginia Supreme Court even receiving a brief from the judges, the Supreme Court issued an order denying our petition. That left us where the judges were free to block us if they wanted, and that has actually very major implications, not just of marijuana cases, but in cases of individuals who cooperate, in cases where we feel that we lack probable cause for misdemeanors or felonies. It was a major realignment of prosecutor/judge power, and one that we’re hoping we may find a legislative fix to in the coming year.

But while we respectfully disagreed with the Virginia Supreme Court, we were left with no options, other than simply to bow out of those cases. Because these were misdemeanors, because the code only requires us to prosecute felonies, we simply walked away. But what we managed to do in suffering a setback in the Virginia Supreme Court is we scored a major policy victory, because during that same period one of our local legislators, Steve Heretick, introduced a full marijuana legalization bill for the 2019 General Assembly term. It failed, but this past term we saw marijuana decriminalization, which is a half step forward; it is not as good as full legalization, but I think Greg Underwood can rightly take a bow for bringing this issue to the forefront in Virginia, for encouraging a dialogue with our legislators, and for pointing out that even when an individual prosecutor was trying to do the right thing, there are going to be institutional roadblocks, and that it was going to be up to the people to vote for Democratic legislators willing to be progressive, and then for those legislators to take the progressive steps in Richmond.

So does that mean the magistrate or the cop is doing the prosecuting themselves? Are they standing in for you in those cases?

That’s right. This is something that happens in most of the jurisdictions in Tidewater and in a lot of jurisdictions elsewhere, and why? Because of money, because of the way the prosecutors in Virginia are funded. Procedurally in a lot of cases, especially down here in Tidewater, the police officer puts on the evidence without a prosecutor there. That’s the way it is for most misdemeanors in Norfolk. We handle a lot of public safety misdemeanors, but the judges, both in district court and now even in Circuit Court, are making sure the clerk’s office sends out subpoenas, and they essentially ask the same questions a prosecutor asks.

It’s still a huge waste of resources…

It’s an immense waste of resources on a lot of different levels. It’s a waste for the amount of time that it takes to write the summons, to field test with drugs, to make sure that the marijuana goes to the labs for testing, to docket the case, to bring the defendant in. It’s hours of labor at all different levels, all for something that is about to be decriminalized, and we are hoping will be fully legalized and regulated within the next year. The other really key problem, and a horrible one for us is that it erodes trust in the community. When police officers are arresting and citing people for marijuana possession, that is hurting our ability to rely on the community to come forward in violent crimes. That is why we think this shouldn’t happen, in a nutshell.

We’re obviously talking a lot about race lately and systemic racism, and this was an important part of the discussion in the Arlington and Fairfax Commonwealth’s Attorney races last year. How big of a problem do you think racism and systemic racism are in the criminal justice system, and how do you think it gets fixed?

Racism is a huge problem, and it’s arguably the number one problem in the criminal justice system. The irony of it is, having worked the prosecutor side of the criminal justice system now for most of my career, it’s really the structures that are more racist than the individuals. I’ve absolutely dealt with racist individuals as a prosecutor, but really the vast majority of the individuals I deal with either are not racist or do not perceive themselves to be acting in a racist fashion. It’s the structures. It’s things like over-policing of disadvantaged communities, over-citation of nuisance crimes, unnecessary escalation of force, that embody the systemic racism. But the problems are much more basic than that. Michael Herring, the recently retired Commonwealth’s Attorney of the city of Richmond, put out a fascinating white paper last year, and in it he discussed the root causes of crime. And the systemic racism we see in the criminal justice system is really the end point of the systemic racism that we see in educational policy and housing policy, in the way we treat the mentally ill, in the way that we treat people to substance abuse disorder. It is a product of mortgage redlining, of community disinvestment, of white flight. Here in Tidewater there there’s been a whole book written about the history of how various counties became cities in southeastern Virginia, as a way of essentially abetting white flight, and of disinvesting in the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth. So there are things that we can do in terms of changing the criminal laws, and we are pushing for those things. But some of the things that we’ve heard about from the Black Lives Matter protesters are things like ensuring the police departments don’t police themselves. For example, here in Norfolk we have an agreement with our Police Department–the State Police investigates every police-involved shooting. The Norfolk Police do not investigate themselves. That should be a law applicable not just to a progressive place like Norfolk, but all over Virginia, especially in the jurisdictions where instead of having a police chief, answerable to a board of supervisors or to a city council, the law enforcement authority is not in a police department, but in the elected sheriff, which is the way it is in many, many of Virginia’s smaller jurisdictions. The elected sheriff is himself often of the same political party, and probably a political ally of the elected Commonwealth’s Attorney.

What about when it goes the other way, when there’s a policeman who’s killed? Do you think that’s something that should be handled by the local prosecutors, given the connection the prosecutors have to the local police–do you think it’s necessarily going to result in serving the community’s interest?

I think the default position in that is that the case should be handed off to another jurisdiction. One of the things that in fact I learned from a Republican prosecutor for whom I worked is that we do not work for the police, and the police do not work for us. That we run on a parallel track in the justice system. So, in a correctly run Commonwealth’s Attorney’s office, the Commonwealth’s Attorney can do this without bias. But I think it undermines the community trust. To encourage trust in the community, it’s important that the Commonwealth’s Attorney in a police shooting where the police officer is the victim, to hand off the case, and there’s a mechanism to do this. One of the things I would like to see as an elected Commonwealth’s Attorney, is an agreement with like-minded progressive prosecutors, such as our office and the offices in Northern Virginia, where we can ensure that the special prosecutor in the case is going to look at the case objectively, and not put a thumb on the scales either in favor of or against the police.

Norfolk has some pretty famously mishandled criminal cases in its history. I’m really flabbergasted by some of the evidence that was not handed over to defense attorneys in a couple of these major stories. In the Anthony Juniper case, for example, there was a phenomenal amount of exculpatory information that the defense attorney was never given, and they had to go back to court and sue over it. [Note, the Fourth Circuit Court actually chastised the Norfolk Commonwealth’s Attorney’s office and prosecutors, saying “We have repeatedly rebuked the Commonwealth’s Attorney and his deputies and assistants for failing to adhere to their obligations under Brady…. We find it troubling that … officials in the Commonwealth’s Attorney’s office continue to stake out positions plainly contrary to their obligations under the Constitution.” This all occurred before Greg Underwood took over the office, and before Ramin worked there.] Where do things stand today in the office–what are your discovery rules, what do you do to make sure that there’s transparency, that there’s a fair playing field?

Excellent question. As far as the Juniper case, unfortunately I can’t comment at all on that because there’s still an ongoing federal lawsuit with our office and members of our office as part of it. As far as your general question, I can speak to what’s going on in the office since I’ve been there in 2012, which is that Greg’s policy as Commonwealth’s Attorney is that the very limited discovery rules in Virginia were not the ceiling, they were always the floor. That we should hand over every piece of evidence in our files, every scrap of paper, so long as doing so didn’t endanger the witness, or endanger an ongoing investigation. We have a very real problem in Norfolk with witness intimidation. We’ve charged more than one person over the last few years with obstruction of justice for making threats to witnesses in violent crime cases, so we’ve had to be mindful of that. But with that exception in place we have been very much in favor of full disclosure. That’s the way I practiced when I was an assistant Commonwealth’s Attorney and frankly I’ve had talks with fellow assistants about that, and now as supervisor, as Deputy Commonwealth’s Attorney, that is my position, that we absolutely should turn over everything, subject to ensuring that the community is safe.

There are new discovery rules coming out in July and we really applaud that, because just like our position on police shootings, we have been ahead of this, despite being less than perfect about it in the past. Those new discovery rules are probably not going to substantially change the way we practice in Norfolk, but we are very excited because we expect them to be a revolution in a lot of other jurisdictions in Virginia where trial by ambush, as it was called, was probably much more common than it has been where we are. We’re very pleased about it, and we feel that it’s not going to make a major change in the way we practice.

Will you commit to never seeking the death penalty? This is something that the Northern Virginia newly-elected progressives have adamantly said.

Let me very clear about this. The death penalty is immoral. It is immoral. There are a lot of people who make arguments about costs versus benefits, and the challenges of false confessions, the money devoted to capital litigation. But I just think about Justice Harry Blackmun, who at 85 said, “from this day forward, I shall no longer tinker with the machinery of death.” We as prosecutors are here to honor a culture of life, to ensure that our citizens stay alive. I will not be a party to the use of state-sanctioned violence against its own people. I will not do it. And I will advocate for the abolition of the death penalty.

What are some of the things that we can do to break up the school to prison pipeline and in particular in the prosecutor’s office? I know Portsmouth Commonwealth’s Attorney, Stephanie Morales is very focused on this–she’s really out in the community, out in the schools constantly, building a strong relationship at a really young age, and letting them see that prosecutors aren’t these evil people that they should be afraid of.

We have had a real focus over the last several months on the school to prison pipeline internally within the office. It’s been a big part of the discussion in the criminal justice reform working group, and part of it is the reality that Norfolk has more juveniles treated as adults than practically any other jurisdiction in Virginia. Greg, as a member of the board of juvenile justice, found this disturbing, and rightly so. And we have looked into it, and we’ve tried to figure out whether it was because of some sort of implicit bias in the system, or because of some other factor, and while we’re still working on it, the preliminary answer appears to be that the only people that we are treating as adults are people who had committed robberies with the use of a firearm involved. But that doesn’t mean that we’re content to stay there.

We are very excited about the fact that the General Assembly has gone on with a position that we’ve long had, which is to raise the age of juveniles being treated as adults. That was something we believed in, and to our surprise the Virginia Association of Commonwealth’s Attorneys went along with that, and it is now law.

We are also very heavily involved in at least one of the same programs Stephanie is involved in, which is the Attorney General’s Virginia Rules Program, and we send every prosecutor we can spare from court to go to our middle schools every year to talk about what the criminal system is, how people get involved in it, and for things that really as a teenager don’t seem very serious. We try to show that we as prosecutors are there to help, and not there to be part of the problem.

But these are first steps. The real fundamental step that we need to take is the step that we’ve seen for Charlottesville. We need to we need to rethink the use of school resource officers or why we have armed sworn police in schools. We need to acknowledge the fact that children in private schools or in wealthy public schools who commit infractions of the school rules are treated as students, where people in underserved schools are treated as criminals, and that has to stop. And we have to ensure that more children are diverted from the criminal system when they are charged on petitions with acts that would be crimes for adults. The system is designed to rehabilitate, but people should be kept out of that system altogether. Once they are in, it changes the course of their life for the worse.

How involved are you with the Virginia Association of Commonwealth’s Attorneys, and given the ideological variation of the Commonwealth’s Attorneys across the state, do you think that they can be an effective organization to speak on behalf of the whole group, or do you think that model needs to be rethought?

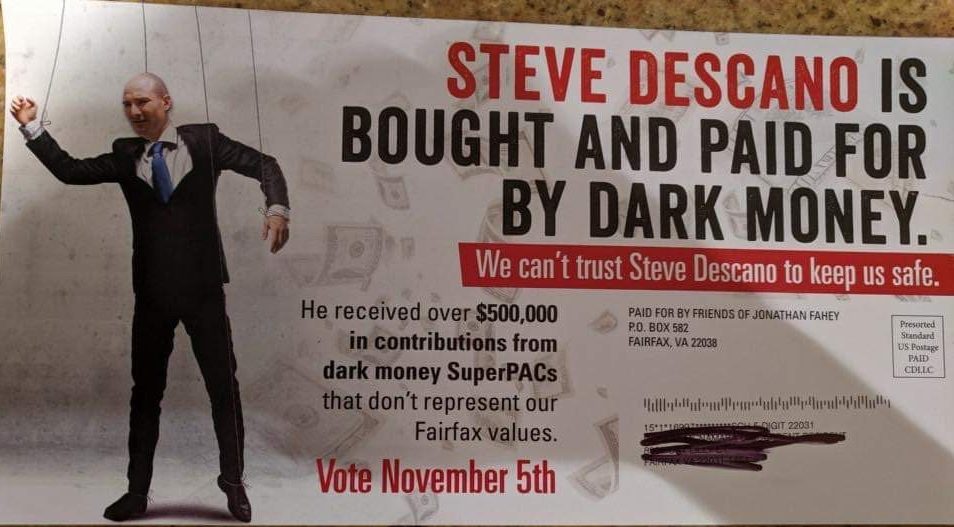

We’ve been involved with VACA over the years, and in many ways in leadership roles. Norfolk is one of the so-called super jurisdictions in the state–that’s one of the largest offices, we’re the seventh largest locality, and we have 40 lawyers, and we have 90 plus lawyers plus staff. Greg has been until really last year, Greg was almost a lone voice for criminal justice reform, and for having a reckoning with questions of race in VACA. If you look, Greg was quoted in the Virginian Pilot last week at a prayer vigil that I attended with him, where he spoke about the death of George Floyd, and where certain members of VACA were in denial about the fact that race is one of the fundamental problems in the justice system. We have always stayed involved because we believe that the way to change the system is to be the conscience of the system, and to continue put pressure on the parts of the system that disagree. That’s what we continue to do with VACA, and now we have help–first with the election of Scott Miles in Chesterfield, and then with the election of the reform prosecutors in Northern Virginia like Steve Descano, Parisa Tafti, Buta Biberaj, Amy Ashworth, and with the election of Jim Hingeley in Albemarle County. With the presence of Stephanie Morales and Joe Platania in Charlottesville, we now have a critical mass in VACA to start changing mindsets.

VACA operates by consensus, which is defined roughly as a supermajority of indeterminate size, and while VACA will speak against more things than it will speak for, in terms of things we agree with, we have the ability to change VACA’s course. Over the long term, I think that what we will see for VACA is that VACA will be most effective when it is talking about what I would call technical or procedural issues–things like funding of Commonwealth’s attorney’s offices, adequate funding of lawyers to review body camera footage, really the mechanics of being prosecutors. But in talking about substantive criminal law I predict that we will probably see VACA speaking not necessarily in unison with progressive prosecutors. I also predict that within the coming years you will see a reform prosecutors group, who will be lobbying for legislation independently. We had a trial run of that this spring. I was in the General Assembly on February the 28th of this year advocating for a very important bill to abolish the jury penalty, and when I stood up I spoke on behalf of five Commonwealth’s attorneys who represented over two million people, and that got the House Courts of Justice committee’s attention and I tell you it got VACA’s attention even more. I don’t expect that you will see VACA as being the only voice–we as progressive prosecutors–if I have the privilege of being elected next year–we will be speaking with a voice, with VACA when we agree with it, but strongly against VACA when VACA stands in the way of progress. Even within VACA, there is acknowledgement that times are changing and that we have to change with the times collectively. But simply moving the center of gravity in VACA is not enough. I personally want to do what Greg has done, which is to get out in front with all the progressive prosecutors who will join me, to advocate for things like the reintroduction of discretionary parole, the ending of the jury penalty, for the wholesale rethinking of the way that we prosecute drug cases, and especially the way we criminalize drug addiction. These are issues that we understand we probably are not going to get VACA on board, but we are going to disagree with them, and we’ll move on on our own.

A couple areas that the legislature did not really make any successful reforms last year were expungement and parole. What are your thoughts on how easy it should be for someone to expunge their records? Right now in Virginia, you can only get an expungement if you were found innocent, which seems like an incredibly high standard. Do you think we should expand it to all misdemeanors, or all nonviolent crimes, or include violent felonies–where should we push on that, and how long of a period do you think the person should have to have stayed out of trouble before you would expunge?

I have a real interest in expungement. One of my duties when I first came to the Norfolk office after having prosecuted elsewhere was to be our expungements lawyer, and I was really surprised at how restrictive our law is. It must be expanded. There were all sorts of situations where we definitely wanted to help the person get something expunged, and the law just wouldn’t allow it, even if we agreed. It’s easier to get something expunged if you go to trial and are found not guilty than it is if the Commonwealth drops the case. Now that that’s not logical, and it’s not just.

As far as expungement of convictions, we need to have a real conversation about this. One of the great disappointments that I had for the marijuana decriminalization bill–first is that it still imposes a major penalty on the poor because it strips the poor of their right to have a lawyer. You’re only allowed to have a lawyer for criminal cases that carry jail time. But the second was that it did not address all of the people who have been convicted of marijuana possession over the last three quarters of a century. There has to be expungement. And I find it a surprise that we can’t even agree that now that something is no longer a crime that it should not be expunged. We also need to have an expansion of what gets expunged in terms of prior convictions where the criminal conviction remains on the books. There are certain crimes that are still on the books that have been found unconstitutional, like consensual sexual relations between two men; there is no reason why these things that never should have been crimes in the first place and are technically unconstitutional shouldn’t be expungeable.

There’s a distinction as far as what to expunge and when that we also need to align with public safety. We as prosecutors, for example, I think need to know a little bit more about a person’s criminal past than an employer or someone looking to offer housing might need to know. And that’s why I favor a big increase in something that I think the average person would call an expungement but that’s probably better called sealing. Which is to wall off information from public view and from public access. That’s basically an expansion of “ban the box” to the world at large. It’s something that I would have to give more thought to about the particulars, but there should be time limitations so after the elapse of a certain number of months or years there should be, for things that are not expungeable, there should still be a sealing option and for certain crimes there should be a sealing option. The only reason that I don’t say expungement for all is that there are simply some criminal statutes where we actually have to know whether there’s a prior record. But just because we as law enforcement or we as prosecutors need to know it, doesn’t mean that it should be an anchor that a returning citizen should have to tow and should have to answer for to every single member of the public, always.

We’ve seen a lot, for example, from Cyrus Vance in Manhattan, that when he adopted his marijuana policy, he vacated and dismissed thousands upon thousands of prior marijuana convictions. We would love to do that, but we have absolutely no legal mechanism to do that. When a conviction becomes final in Virginia, almost without exception it is indelibly marked, it is there forever. What I’m talking about is not radical. There are models for it elsewhere. It’s simply asking that Virginia give us as prosecutors or give returning citizens and citizens the opportunity to avail themselves of something that if they were New Yorkers, for example, they would have.

Are there any crimes that you would not want people to have the ability to expunge eventually?

Any crimes involving violence I think are crimes that it is in the public interest for people to know about. This really goes back to having a culture that honors life, and a culture where safety of the citizen is paramount. For example, it would be irresponsible for someone who’s interviewing a candidate for a long-term care facility, a caregiver for disabled individuals, to be barred from knowing that that individual has repeated convictions, for example, for sexual assault or for child abuse. Essentially it would make the state complicit in allowing people who have these convictions to put themselves in a place to possibly reoffend. It doesn’t mean that those people should not be considered at all, it doesn’t mean that those people should be banned from being part of society. But we also have a responsibility to the community at large that with certain classes of crime, some certain forms of inquiry, that they know. That’s the whole idea behind the sex offender registry, it’s the same thing. What the exact outlines of it would be I’m willing to consider, but I do think that the expungement of all crimes no matter what the circumstances would not be consistent with keeping our citizens safe.

As far as parole, where would you expand on our parole, or would you leave it alone?

We need to expand parole. This goes back to honoring a culture of life, and having community trust. The parole system that Virginia had up until the 1990s wasn’t a good one, and the reason was that it was what’s known as mandatory parole. The way it worked overall is that when somebody did a certain portion of their sentence, they would get out, and that wasn’t really parole. All it was was that it would inflate whatever the top line number was so that the person convicted would serve the amount of time people wanted. What we want instead is discretionary parole, and the reason we want that is the purpose of parole is to allow people who have repented and reformed to reenter society. It is an opportunity for someone who has committed a crime, and often a very serious one, to demonstrate that he or she is ready to rejoin the community earlier than what the judge or jury felt was appropriate. This is a human rights issue. Every person who’s committed a crime should serve every day that they should serve, but every day that they serve beyond what is necessary is unjust and is an injustice. It’s expensive, it’s immoral, and it’s not necessary. So those of our inmates who have truly reformed should have a mechanism to get out, and the mechanism that we have right now is completely inadequate to that task.

Does Norfolk currently have specialty dockets, like a drug court, a mental health docket, and a Veteran’s court?

We do, and we have more. Norfolk was one of the pioneers in the alternative sentencing docket movement, and Greg, my current boss, has a lot of credit to claim there. We have a drug court, we have a mental health court, we have a re-entry docket, we have a Veteran’s tract which is a dual track for Veterans who may have mental health issues or substance abuse issues. We are in the process of creating a juvenile alternative disposition court, one that recognizes that mental illness and substance use disorder tend to be co-occurring in children. We devote a prosecutor exclusively to the administration of these dockets. We also use our alternative treatment courts as a component of our community outreach programs. We also just recently opened the first Family Justice Center in Virginia with a large grant from the Department of Justice, and we are using that to reach out in innovative ways to victims of family violence and domestic violence. We have been big believers in the alternative treatment court model, but we have been pushing the envelope on that too. We would like to see the General Assembly also expand some of the power that the Virginia Supreme Court said that we did not have to allow for pre-arraignment diversion, and for the creation of other alternate diversionary programs to try and treat mental illness, substance use disorder, and poverty as social issues rather than crimes.

Greg Underwood deserves a tremendous amount of credit for the work that he has done. He has been willing to do the substantive work and to accept the results and not trumpet what he’s done. That’s not to say that they shouldn’t get exposure, and I think that it’s very important that people nationwide know what progressive prosecutors are doing, so that they can see what the realm of possibility is. But I would love to champion the fact that here in Norfolk, unlike in the races last year, where progressives were looking to oust a regressive system, that we have been pushing the envelope on progressive reforms and reckoning with the criminal justice system and that my campaign would be about extending the good that we are doing, multiplying the good, rather than simply undoing the bad.

Do you have ways of measuring the success, in terms of lowering crime rates or keeping kids in school, what ways do you have to measure the success of some of these progressive policies?

The point that you make is one that we have been trying to work on ourselves, which is how to show empirically that what we we’re doing works. The criminal justice reform working group is mostly like-minded prosecutors from our office, but it also includes two professors from Old Dominion University who work in the sociology department and specialize in criminal justice matters. They have been working over the last year and a half on our bail policy–a policy that should have been all over the newspapers because of how important it was but would up being underreported and overshadowed by our argument with the judges over marijuana. We are doing what we can to see if we if there is a measurable effect on either the number of people being held or on crime one way or the other from our decision to try and eliminate cash bail. This is probably the number one largest issue that I would tackle coming into a new administration is how to measure these things. We have a sophisticated case management system in our office, for example, that costs a half a million dollars three hundred thousand dollars of which the City of Norfolk paid and two hundred thousand dollars of which came from forfeiture money, which itself is sort of a morally mixed blessing, but the quality of the data coming out of that system is only as good as the quality of the data going into it and I think that we could probably do a better job with that. But that is only the data about cases that come to us. The police have wide discretion, and discretion we encourage them to use not to charge people and to allow people to go with warnings for a whole host of things. So measuring that data becomes more difficult. The Virginia State Police puts out a very good report every year on crime in Virginia, but we would like that data to be more granular.

Can you describe the funding system for Commonwealth’s attorney’s offices in terms of money that they received from the state–is it a flat amount, or do the funds vary based on some kind of performance standard or goals, or number of cases or whatever, and how would you like to see that reformed?

This is a system absolutely needs reform. It’s a system frankly that’s a lot like the system for schools. It’s one that that allows wealthier jurisdictions to put a lot more resources into prosecution and that really hurts smaller and less wealthy jurisdictions. The Virginia Constitution and the statutes of Virginia say that prosecutors are only required to prosecute felony cases, and a certain limited class of civil cases–unusual things like the restoration of your right to have a firearm, or the denial of your right to register to vote. So the main funding for Commonwealth’s attorney’s offices comes from the state, from the General Assembly, and it’s funneled through a body called the State Compensation Board. That board doesn’t just divvy up money for Commonwealth’s attorneys, they have different pots for Commonwealth’s attorneys, treasurers, sheriffs, clerks of courts, commissioners of the revenue. The way the state does it is, they set a fixed headcount for all of Virginia, and they’ll say in the biennial budget there will be this many prosecutors in Virginia. I don’t have the exact number but it’s roughly 700 prosecutors, I believe. That is a pie that only shrinks and grows depending on the General Assembly. The Compensation Board is then tasked with cutting up that pie. The system currently in place is inequitable. The measure that is used to cut up that pie is felony charges brought to Circuit Court, to the trial court for felonies. That’s unfair in a number of different ways. First of all, it doesn’t count any misdemeanor cases, so any prosecutor who prosecutes a misdemeanor is essentially doing it without any funding, and has taken away resources from prosecuting felonies. It’s also unfair because it doesn’t consider the severity of a felony, so a third offense shoplifting of five dollars’ worth of soap, which is a felony, will be counted the same as a homicide. They will each be one–they are unweighted, which massively disadvantages jurisdictions that have a high incidence of violent crime, which takes much more time to prosecute.

It is also unfair because it creates incentives in the system to over prosecute. Because the unit of measure is felony in Circuit Court, if a progressive prosecutor chooses to exercise discretion and to reduce whole hosts of felonies to misdemeanors, if that $5 third offense shoplifting gets reduced to a misdemeanor, it is no longer counted in the numbers for that jurisdiction. So jurisdictions that choose to essentially show mercy are penalized by having prosecutors taken away; and jurisdictions that choose to pursue the most serious charge in every instance will have more prosecutors proportionally. The final way that this is unfair is, aside from encouraging overcharging, even if charges are brought to Circuit Court and then reduced, that’s essentially taxing the defendant to ensure that there’s a number available for the staffing standards. Now if somebody would say “well, what’s the harm, the defendant pleads guilty to the misdemeanor in Circuit Court instead of district court?” The harm is hundreds of dollars of additional non-waivable court costs that the defendant is saddled with, who is almost always indigent.

Forgive me, there really is one other point which is that there are a whole host of non-felony incidents that are very very important to Public Safety: misdemeanor domestic violence cases are a leading indicator for homicides. It is crucial that they be prosecuted with a prosecutor, but they’re not required to be by statute. The possession of concealed firearms illegally is a leading indicator for homicide, but we are not funded to do that, so we have to steal resources from other places to do those things. This is inequitable because larger and wealthier jurisdictions will allow additional prosecutors, and pay for them out of city or county funds to do these things; poorer jurisdictions who don’t have the money can’t do it. The Compensation Board numbers are also only flat numbers–for the vast majority of prosecutors, it’s just over $50,000 a prosecutor, which means that poorer, smaller jurisdictions they’re paying massively below market, and wealthy jurisdictions can supplement salaries for prosecutors and poach talent from other places, and also offer lower workloads as a benefit. So all of these systems need to change.

The good news is that there is a working group populated by Commonwealth’s attorneys–including progressive prosecutors–who are working on changing these staffing standards. They are going to hopefully present a plan later in the year that we’ll be able to tinker with the current system and hopefully make the allocation of the pie a little bit more realistic. But the real change for this needs to come from the General Assembly, and the General Assembly needs to recognize that just as they should expand funding for indigent defense, to make up the unconscionably low pay for defense lawyers, they cannot prosecute on the cheap either. If they expect us to give defendants their due process, we have to have the time and the resources.

I know there’s a $227 fine that the defendant pays when their felony gets reduced to a misdemeanor. Is that related to the fact that there’s no incentive to prosecute misdemeanors and an incentive to overcharge—is that supposed to even it out, but it comes at the cost to the defendant?

With only one or two very small exceptions, these fines or costs either go directly to the city or go to the State Treasury or some combination of the two. So the felony reduced to misdemeanor or court cost this assessed, it doesn’t wind up, for example, getting turned back to the Compensation Board and then reinvested. It’s money that theoretically would go to the general fund if it’s ever collected, which much of it is not. So my best understanding of that is it’s perversely meant as a sort of discount if you’re found guilty of the felony, the court cost or if you want to think of it as a so-called processing fee, is higher, but it’s less than if you were ultimately convicted of a misdemeanor. Now the discussion of non-waivable costs itself is a major and untold social justice issue. The law enforcement and the administration of justice, even for the most hardcore libertarian, is a core function of government; short of preventing foreign invasion it is the most basic form of government. It is immoral to tax the indigent and essentially to make them pay for the stick with which we beat them–that is inappropriate. As a general matter, I do not believe in fining people. I believe that if something is sufficiently blameworthy then a jail sentence is the way to do it, not a fine. But we need to get away from this model of court costs as essentially a regressive tax on the poor; it’s not just on individuals charged with crimes, inevitably it’s the families who wind up having to try and pay these things off and it is one of the major invisible inequities in the system.

Did you have anything that you wanted to add that you thought we didn’t touch on?

This a very exciting time to be a prosecutor, and an especially exciting time to be a progressive prosecutor. I entered this profession 14 years ago believing that the war on drugs was causing more harm good, that there needed to be a rethinking of our drug laws, that the sentences that we were pursuing were unduly punitive, and the system needed to change. But especially as a junior prosecutor, I wasn’t in the position to breathe this to anybody. To see these attitudes, and the recognition of the root causes of crime and social problems, as part of a mainstream conversation, to see police brutality and George Floyd at the center of protests all over America, and to see that people really understand that the criminal justice system needs to change, it gives me hope for the moral arc of America. And having worked for a progressive prosecutor, I really feel called to carry on this movement, and to ensure that we can make the system as fair as we can for all people.