Excellent column by former VA House Dems Leader David Toscano; definitely read the whole thing, which argues:

“Before embracing the fatalistic belief that humanity is doomed, however, perhaps we can draw inspiration from the actions of their young activists in the state of Montana, who recently won a victory in Big Sky Country, using state Constitutional provisions and a legal theory called “Public Trust Doctrine” to win a court battle designed to combat global warming.”

Also, see below for the part of the article dealing specifically with Virginia, and arguing that to amend Virginia’s constitution to seriously protect our environment, “it would likely require that Democrats control both chambers of the General Assembly for at least four years” – especially given that “[e]vidence of climate change denial is rampant with Virginia’s GOP and found in many of Youngkin’s actions.” So if that won’t work, then what are the other options?

- “include a public trust argument in the suit against Youngkin arising from his actions to withdraw from RGGI. The Supreme Court of Virginia could find that Article XI recognizes and expands a public trust without overruling earlier decisions.”

- “With all this Constitutional uncertainty in Virginia and the time and challenges involved in pursuing exclusively legal strategies, the best approach likely remains winning at the ballot box. A progressive legislature and Governor will have more impact than slow churning lawsuits.”

Both of these suggestions make a lot of sense, and we should definitely do both. But will we?

**************************************

REINVIGORATING VIRGINIA’S ARTICLE XI

Virginia’s present Constitution was rewritten in 1971, during the height of the environmental movement. Perhaps because of that, the document includes Article XI, which proclaimed that the policy of the Commonwealth was to protect its water, air, and natural resources. Unfortunately, and unlike other states’ “green amendments”, the provision never states that there is a “right” to these protections, making it much more difficult to enforce. And unlike Montana, there is no language related to public choice doctrine in our Constitution, and our courts have largely ignored the concept as a basis for protecting the environment.

Is it possible in this political climate that our Constitution could be strengthened to make it more useful in fighting climate change? We could tweak Article XI by inserting a key phrase or word, but that may not be enough. A more effective approach might entail enacting an entirely new amendment establishing the right to a stable climate, and to locate the provision within our Bill of Rights. This would accord it status as one of our fundamental rights, making enforcement easier. Such a measure would have wide support. But amending the Virginia Constitution is very difficult; it requires language to be passed in two successive legislative sessions separated by an election, and then approval by a majority of the voters. Given the political climate, it would likely require that Democrats control both chambers of the General Assembly for at least four years.

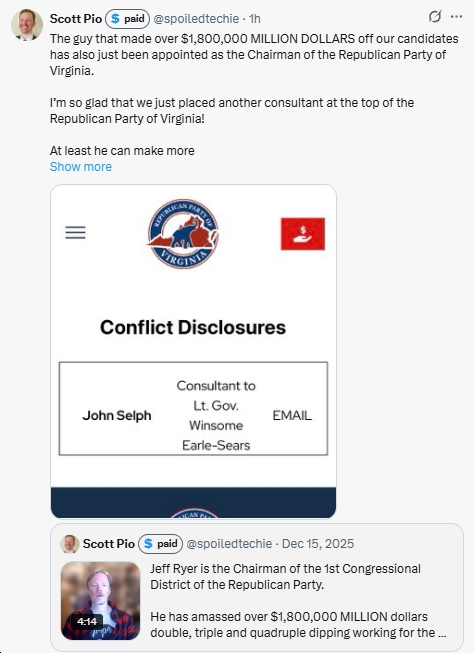

While the governor’s signature is not necessary to enact an amendment, our present chief executive and his party would provide substantial opposition to such an amendment. Evidence of climate change denial is rampant with Virginia’s GOP and found in many of Youngkin’s actions. Most recently, he has attempted, without legislative authority, to remove the state from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), the consortia of states who have joined together to combat climate change in ways the federal government has been unable to do. We have seen the Virginia GOP oppose the Virginia Clean Economy Act and propose rollbacks at every opportunity. Such a Constitutional change will not be easy.

The legal arena nonetheless presents the opportunity for a new generation of lawyers and a reconstituted state supreme court to breathe new life into Article XI and public choice doctrine to address climate change issues. There is a strong argument that the drafters of Article XI not only intended it to be a “mandate”, that is, a self-executing means compelling state officials to consider environmental impacts in all decisions, but also as a statement that Virginia’s land and waters are to be held in trust for its citizens. One way to test this approach might be to include a public trust argument in the suit against Youngkin arising from his actions to withdraw from RGGI. The Supreme Court of Virginia could find that Article XI recognizes and expands a public trust without overruling earlier decisions.

With all this Constitutional uncertainty in Virginia and the time and challenges involved in pursuing exclusively legal strategies, the best approach likely remains winning at the ballot box. A progressive legislature and Governor will have more impact than slow churning lawsuits.