I find myself wondering something about the idea of God. It grew out of my noticing the strangeness of the contrast between two important cultures in the millennium before the birth of Jesus: the culture of the ancient Greeks and that of the ancient Hebrews.

I find myself wondering something about the idea of God. It grew out of my noticing the strangeness of the contrast between two important cultures in the millennium before the birth of Jesus: the culture of the ancient Greeks and that of the ancient Hebrews.

Here’s the thing. These two peoples/cultures inhabited basically the same world – empires, metals, lots of war, slavery, annihilation-but despite that sameness they can to very different conclusions about a question of a matter most fundamental to worldview: the question of having God or the gods at the center of the cosmic order

Which is it, and what might be the fundamental difference between the cultures that would account for such different ways of seeing the fundamental order of the world.

The Greeks saw the world of the divine beings as a plurality, a whole diversity of gods having dealings (not always admirable) among each other. A many-ness, and a strong flavor of amorality.

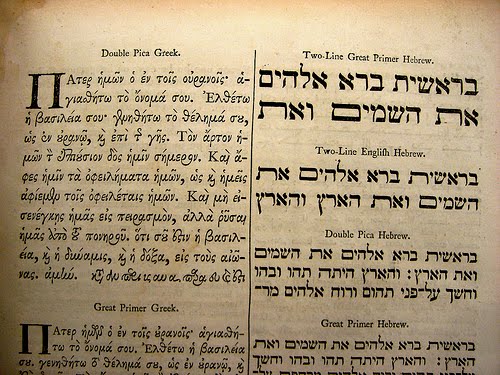

The Hebrews saw the world of the divine as inhabited by ONE GOD — and indeed from Abraham onward that was THE defining feature of the Hebrew religion, and is still at the center of the basic Jewish prayer, the Shema Yisrael: “Hear, O Israel: the LORD our God, the LORD is one”

So it looks like the Hebrews at least would have said that the difference between believing in One God or in many gods was of the utmost importance.

Which is what leads to the question:

Is it a really fundamental matter about how to perceive reality, and if so, what can account for how these two cultures living choosing so differently on this matter despite inhabiting the same basic world?

Did their cultures give them basically different ways of thinking? If so, what was that difference? Or did they come to have different needs, or different senses of the nature of life, growing perhaps out of different historical experiences?

For example, the Greeks had a pretty good won-loss record, and were basically feeling like winners in the cruel intersocietal game. It is a Greek (Thucydides, whom I have quoted in just about every one of my books and in many of my public lectures, who put these words into the mouths of the Athenians:

“The strong do what they can, while the weak suffer what they must.”

The Greeks had themselves taken their domain from another group of human beings, if I remember the narrative about the spread of Aryan peoples out of the area of Iran? The Greeks are more the kind of “We’re # 1” rowdy group in the lockerroom boasting and spraying champagne around. Not a lot of reason to question whether the world is good the way it is or should be improved. A lot of reward for indulging the impulse to come out on top in a contest for dominance.

The Hebrews were generally not in a position to get into this kind of lust for power.

The Hebrews/Jews were sandwiched in between mighty empires — the Egyptian (four centuries of slavery), the Bablyonian (the generations of captivity), the Assyrian (the defilement of the Temple). And these Hebrews were motivated to see the world as more ordered, and ruled by a power of more emphatically moral character, to weigh against their traumatic experience of the lack of a moral order and of power being wielded by an evil force.

All that pondering then leads me, for whom “Pursue the Truth” is a driving force, the question arises: If that picture I just painted is a substantial piece of an answer, is the effect of that explanation to increase or decrease our assessment of the validity of the different choices?

Would this picture provide support for the likely rightness of the perception, or would it undermine it? Which side should we be listening to, if either?

I make no pretense to know about what kind of divine beings there might be, or if there is anything like that in the cosmos or not. But here is how I might see a relevant case being made in either direction.

On the one hand, one could say this picture discredits the belief in one God. One might say that this idea was, for a victim society, a kind of opiate– at least a killer of some pain.

At least things make sense, in some ultimate sense,” those wanting their afflict to make sense, despite the pain. “At least in some invisible world of God’s justice, the wrongs will be righted.”

That would be comforting for a much-victimized people to believe.

But on the other hand, one might reasonably argue that their experience could lead them to see more deeply into the way things are and the way things should be, since the way things are has often been so painful.

The people who have experienced victimhood — conquered, killed, hauled into slavery — are driven by their suffering to see deeply into the big picture, and they see the reality of the battle between good and evil, and the moral obligation to serve the good and defend the sacred. They know that injustice is bad, because they experience its badness in their bodies and their souls.

In this way, their experience compels that people to think about the deep problems in the condition of humankind– in a world in which the problem of uncontrolled power has subjected the human world to a ongoing force of brokenness stretching through the millennia (and into our times here in America).

Their experience leads them to perceive a deep reality of prime importance– a reality that could reasonably be called “the battle between good and evil.”

Anyway, those are the places my wondering took me today, when I somehow stumbled into the question of God or gods, and the mystery of how worldviews of these two cultures came to be so different on a fundamental question about the structure of reality.

Not just any two cultures, either. These two –Athens and Jerusalem– together, constitute the two basic building blocks of the civilization, the two main cultural streams out of the ancient world, that have shaped the civilization of which we are in America are part.

I say there are important truths from both of them.

Hurrah for the Greeks, for example, for providing some of the important tools for clear thinking as a way of understanding things, and some foundation for our pursuing truth through the use of reason and evidence.

But hurray also for the Hebrews for seeing deeply into the profound moral dimension central to the circumstances of civilized humankind.

These things all come together in my new book, which addresses the question: What has gone wrong in America, and how can we set it right?

And these questions are being asked at a time when we Americans have been turned into the role of victims– as our power and our economic status and the prospects for our children and grandchildren are being taken from us.

And we are called to perceive WHAT WE’RE UP AGAINST, which should bring us to utilize the biblical sense of the centrality of the question of moral order, and the battle between good and evil.

The strategy I propose:

See the evil. Call it out. Press the battle.

I offer this book as a weapon for that battle.

Forgive my boldness, but I feel compelled to be bold enough to claim that WHAT WE’RE UP AGAINST presents a picture containing truths that have the potential to have a meaningful and beneficial impact on the battle against a consistently destructive force that has arisen on the right, and that has properties that make it fully appropriate to call it a force of evil.

This book provides — n a purely secular way, in a logically structured way fortified by evidence before our eyes — presented a picture of what’s going on in this profound national crisis we face in America in these times. And it shows that there’s something visible that should lead many in Liberal America to make a revision in their worldview, a revision that will be empowering.

The stakes in this could not be higher.

It is a coming together of Athens and Jerusalem.

The picture is developed in ways that meet the intellectual standards that have their roots in the ancient Greek thinkers. And it is infused with a moral spirit that has some real connection to that spirit that speaks in the Bible when some Hebrew figure stands up to speak the moral truth to evil power.

See the evil. Call it out. Press the Battle.

Here now a book written to be a weapon people could use in that battle.