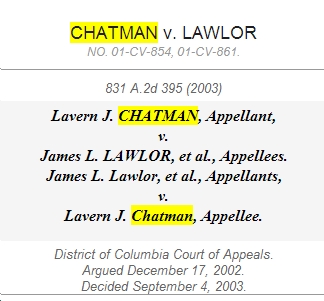

Earlier today, I reached out to the Lavern Chatman for Congress campaign for comment on something troubling that’s been floating around. “Floating around out there” includes chatter among multiple 8th CD political operatives, as well as forwarded emails about a court case and at least one Facebook posting on the subject. Personally, I hadn’t known anything about this until very recently. What is “this” exactly? See below for excerpts from the court ruling, in which “Appellant, Lavern Chatman, seeks reversal of the trial court’s decision to hold her jointly and severally liable for $1.4 million in punitive damages because of her involvement in a fraudulent conveyance.” In the end, the judge affirmed a previous “finding of liability, based on sufficient evidence of malice, and…sustain{ed} the court’s decision to award punitive damages in some amount” against Chatman.

Earlier today, I reached out to the Lavern Chatman for Congress campaign for comment on something troubling that’s been floating around. “Floating around out there” includes chatter among multiple 8th CD political operatives, as well as forwarded emails about a court case and at least one Facebook posting on the subject. Personally, I hadn’t known anything about this until very recently. What is “this” exactly? See below for excerpts from the court ruling, in which “Appellant, Lavern Chatman, seeks reversal of the trial court’s decision to hold her jointly and severally liable for $1.4 million in punitive damages because of her involvement in a fraudulent conveyance.” In the end, the judge affirmed a previous “finding of liability, based on sufficient evidence of malice, and…sustain{ed} the court’s decision to award punitive damages in some amount” against Chatman.

In sum, the court found that Chatman helped Roy Littlejohn, “a longtime friend and associate” with “a friendship and business relationship spanning fifteen years,” to avoid paying his 297 employees (of J.B. Johnson Nursing Home) $1,447,651.99 in wages. In addition, Chatman was found by the court to have allowed Littlejohn to “transfer” his assets to her in a manner the court found to be illegal and malicious, the aim of which was to help Littlejohn evade the court judgment that he pay the back wages.

Here’s an excerpt from the D.C. Court of Appeals’ ruling on September 4, 2003:

After a three-day non-jury trial, the court found appellant and Roy Littlejohn liable on all three counts of the complaint, but also found that “the evidence was not sufficient to show that Mrs. Littlejohn was involved in the fraudulent transfer ….” The court explicitly rejected appellant’s testimony, finding it to be “patently incredible.” It further found that “the papers drawn up by the parties were entirely bogus, and that anyone with Ms. Chatman’s background and sophistication knew it.” The court was therefore satisfied that “the plaintiffs have demonstrated by the preponderance of the evidence that the two were engaged in a civil conspiracy to defraud.”

The court also found appellant and Littlejohn jointly and severally liable for $1.4 million in punitive damages, ruling that there was “clear and convincing evidence that Mr. Littlejohn and Ms. Chatman acted with evil motive, actual malice and with willful disregard for the rights of the plaintiffs.” The court characterized their behavior as “outrageous and grossly fraudulent,” especially considering the disparity in wealth between appellant and Littlejohn and the “people whom they scammed.” The court also described the transaction as a “deliberate scheme to get around a lawful judgment,” and stated that in its opinion “each defendant needs to be punished for their conduct [and] each defendant needs to serve as an example to prevent others from acting in a similar way.”

[…]

The record in this case supports the trial court’s finding, by clear and convincing evidence, that appellant’s conduct was outrageous, grossly fraudulent, and in willful disregard of the employees’ rights. We cannot overlook the massive scale of the fraud, which was designed to defraud not just one, but 297 persons. Another factor making appellant’s actions particularly egregious and oppressive was the enormous disparity of wealth between appellant and the employees. While her exact net worth may be a matter of debate, as we shall discuss later in this opinion, she is indeed a very wealthy woman.9 As for the employees, the trial court described their situation by stating, “based on the type of employment that [they] had … people in that economic situation … literally suffer when they don’t get a paycheck.” Yet, despite the employees’ precarious financial situation, which was attributable in large part to Mr. Littlejohn and the collapse of Urban Shelters (as the first lawsuit showed), appellant willingly engaged in a fraudulent transaction with Mr. Littlejohn that prolonged their financial distress by forcing them to endure yet another lawsuit in order to receive their due compensation.

Although appellant does not challenge the court’s finding that she knowingly and willingly participated in a fraud, she does argue that a finding of malice cannot stand because she did not have actual knowledge of the judgment against the Littlejohns when she entered into the fraudulent transaction. According to her logic, in order for punitive damages to be awarded, it is not enough that she willingly committed fraud; in addition, she claims, she had to know exactly who was being defrauded. This somewhat novel argument overlooks the trial court’s factual finding-which was not plainly wrong or lacking in evidentiary support-that appellant was indeed aware that she was defrauding the employees.

So, those are the legal facts of the matter. Now, here’s a statement by the Chatman campaign, which they sent me a few hours after I asked them about this case earlier today.

STATEMENT OF LAVERN CHATMAN

This series of events was a nightmare scenario. My first husband had just died after a long battle with lung cancer and his estate was still not settled. After that, a former employer and someone I thought was a trusted friend came to me in need of a loan. Without asking tough questions, I agreed to a loan where he signed over property to me as collateral. Given this tough time, I didn’t pay much attention to the details.

I had no idea of the financial chaos of Mr. Littlejohn’s business: he was broke, his employees were suing him and he had a pending judgment against him. Even though I didn’t know what he was doing and I was mourning, I should have asked more questions. I take responsibility for that.

During the worst year of my life, this is one instance of bad judgment, not an example of any bad intentions. I did not stand to benefit and I did not know about Mr. Littlejohn’s grand scheme, but I was forced to pay for his mistakes since he was insolvent at the time.

At a different time in my life this would have never happened.

That said, I take personal responsibility for my involvement. I certainly learned a great deal from this. It’s an example of how you can make a serious error, not through bad actions, but from not asking enough questions and through inaction.

I am now the type of leader who asks the tough questions.

Before and since 1998, I’ve dedicated my life to giving back. I’ve run three community organizations and I have mentored dozens of young people to encourage them to make good financial and life decisions.

Personally, I’m having trouble reconciling the court’s clear and strong language with the Chatman campaign’s statement. Also, a “loan” (what the Chatman campaign calls it) and a “fraudulent conveyance” are very different things. What do you think?

P.S. My understanding from multiple sources is that the Chatman campaign polled on this issue a while back, to see if it would make voters less likely to support her. So, the Chatman campaign clearly were/are aware of it.