[You can find the earlier entries in this series here.]

Understanding Evil

The effort to understand evil has a long history in our civilization.

At a minimum, people have felt a need to be able to answer the question, “Why is there so much brokenness – wrong-doing, trauma, suffering – in the world?” Or, to put the question in terms of “evil,” as many have done: Why is there evil? Where does it come from?

When people have also sensed that this “evil” is something bigger than just the brokenness that characterizes one thing or another, that it should be seen as an actual “force” operating in the world, there have also been the questions: What is the nature of evil? And how does evil operate in the world?

These are important questions for understanding the human story, and for understanding what has gone wrong in America in our times.

But they are not questions that are widely asked in Liberal America in our times. Not asked for a couple of reasons.

The op/ed piece I quoted here earlier, “Liberal America’s Great Sin,” began with my brother saying, “Well, Liberal America can finally see evil, they can see it in Trump.” In that piece, I offered a reason why most of Liberal America failed for so long to see the “evil force” – until it was personified in such a grotesque person as Trump — that was gathering in our nation.

Liberal America [I wrote] lacks the habit of putting the pieces together to see things whole. So something diffused into the body politic — in the hypocrisies of the once-respectable Republican Party, in the deceptive messaging of the right-wing media, in the degradation of the consciousness of the Republican electorate – can escape notice.

In that op/ed, for reasons of length, I restrained myself from identifying another major reason for Liberal America’s blindness to the rising force of evil: many simply do not believe that the idea of “evil” refers to anything real in our world.

I would suggest that those two aspects of much of contemporary (secular) liberal thought – not seeing how the pieces fit together into something bigger than the pieces, and not believing there’s any such thing as “evil” – are different aspects of the same thing.

That is, they are connected because, as I will be trying to show here, the force worth calling “evil” becomes visible to us only if we step back from the concrete pieces and witness something coherent operating in the world through time.

The Problem of Evil

I’ve been looking into the problem of evil, off and on, my whole adult life. If there are very illuminating or satisfactory answer out there from secular thinkers, I am unaware of them.

But the only answer I’ll discuss (among those I find unsatisfactory) is the major answer provided by religious thinkers in the Western (mostly Christian) tradition.

These thinkers faced a real problem—given the image of God they felt a need to protect.

They could not help but recognize that the world is broken – i.e. that there is evil in the world. But the challenge was to reconcile that unescapable reality with their image of God as both all-good and all-powerful. How could the world created by such a God contain so much evil? (Theirs is the problem called, historically, “theodicy.”)

I truly sympathize with their dilemma. I, too, would wish to believe that the world we live in is created and is still (in some important sense) ruled by an all-powerful, all-knowing, all-good Being. But there is no good way of reconciling that notion with the evidence of the world.

If there were a truly satisfactory answer, the religious thinkers would have come up with it. But there isn’t. But some answer was needed to explain all the brokenness in the world, so they came up with one. Unfortunately, their answer doesn’t work.

What they came up with, to identify the sources of evil, have generally boiled down to some gesture in the direction of something called “free will.” Humans are free to choose, they say, and when people choose evil it’s their fault.

The idea that Evil originates within humankind does salvage that image of the all-good, all-powerful, all-knowing God. But it does so at the expense of blaming the victim. (Which in so many ways seems to be a deep dynamic embedded in civilization.)

But worse, the “free will” answer protects the “given” about God at the expense of making sense. (While some notions of “free will” make sense, no idea of “free will” both makes sense and solves the problem of explaining so much evil in the Good Lord’s Creation.)

The problem with the “free will” answer the religious thinkers offered is not so much that it’s false as that there’s no way it could be true. Just like 1 + 1 = 3 can’t be true.

(Posted on the Series website here is my argument to justify my dismissal of the “free will” answer. It presents what I claim to be a logical proof of almost mathematical tightness that there is no conceivable concept of “free will” that serves the purpose of putting the ultimate responsibility for the existence of evil on human beings. What I claim to prove there is this: Yes, we choose, just as we experience ourselves as doing. But the ultimate source of the way we choose must necessarily lie outside of ourselves. This piece is a passage from my 1989 book, Sowings and Reapings: The Cycling of Good and Evil in the Human World.)

Much that is important for understanding the human story – the challenge we face as a species, our possibilities for meeting that challenge – is visible in the contrast between the “free will” explanation, which places human sinfulness at the root of evil, and the explanation that I will offer here, which finds the root at an entirely different level.

One view focuses on the concrete manifestations of evil-doing—people doing destructive things. The other steps back from the immediate and focuses on the forces at work in the overarching system into which we are born, and by which, inescapably —from conception onward– we are shaped.

One asserts a logical impossibility– the creature self-creating itself ex nihilo, driven by choices formed outside of the nexus of causality. The other sees us as necessarily the fruit of the world, inescapably enmeshed in a large and dense network of cause and effect.

One blames the victim; the other shows us to have stumbled innocently into an impossible situation that inevitably unleashed a force of brokenness—a force that injures and damages us, that turns us into agents of brokenness, and that still reverberates in the human world.

Let us look further now at the systemic forces – of brokenness, but also of wholeness – that humankind has been swept up in.

Follow the Pattern of Brokenness

The human story is not specifically a story about evil. It should be understood, rather, as the story of a creature that, like all life, strives toward the fulfillment of life’s needs.

But the problem of evil did arise when this creature, enabled by its unprecedented strengths, stumbled into territory into which no other creature had ever before ventured. And as a result, in this terra incognita, this creature unleashed into its world a force of brokenness. All with the result that, for millennia, it has had to contend with the problem of evil.

Thus it is that the answers to the questions about the nature and origins of evil dwell inextricably in the heart of the human story. And, accordingly, these answers are part of what makes the understanding offered here “A Better Human Story.”

As I have argued in earlier installments (especially #4 and #5), that –with the rise of civilization– brokenness was unleashed into the human world through no fault of humankind, and for reasons that no way demonstrate evil to be inherent to the nature of the human creature.

The new form of life (civilized society) that arose inevitably precipitates a new kind of disorder into the human world. And this new kind of disorder delivers a powerful and lasting impetus of a new kind of brokenness into the human world.

We will soon be looking at how that brokenness moves through the human system. An essential concept for understanding the reality of “an evil force” (or “a destructive force”) is the idea of “a pattern of brokenness.”

What do a war and the people traumatized by that war have in common? One can see in each of them something that’s broken, and not whole. One displays brokenness at the level of the intersocietal system, while the other is brokenness at the level of the psyche of individuals.

Very different manifestations, but they share something essential that makes them kindred. That “something” can be conceived in terms of a “pattern of brokenness.”

But of course, they have another connection (beyond this shared structure of “brokenness”– because it was the war that transmitted that brokenness to the traumatized people.

So the second conceptual step in understanding evil is to follow the pattern as it gets transmitted through the system over the course of time.

The brokenness continually changes its particular manifestations. Whether the brokenness is in Form A or Form B, whether it is in a society or a family or an individual, the pattern of brokenness is discernible, as is that pattern’s tendency is to transmit itself to whatever it touches, at whatever level, in the human world.

This impetus of brokenness, therefore, can be seen moving through the human system through time like a wave through water. Our attention tends to be on what is specific and concrete. With a wave, what is concrete is the water itself, which just bobs up and down. But there is another dimension of reality – the wave.

The wave works through the water but is not the water. The wave we see moving cross-wise, even if the water itself does not. Each bit of water does its thing, in place. While the wave moves on. It works similarly with brokenness in the human world.

We tend to look at the brokenness at the concrete level. Like, say, Donald Trump. Brokenness on the human scale, and thus readily visible. Important, and certainly interesting.

But to understand evil, we must perceive more than the water we’re standing in. We must look at the wave moving through the system over time—the wave that transmits the energy derived from some impetus that entered the sea.

It is in terms of such “impetus” that, as we will see, the inescapable ongoing dilemma described by the parable of the tribes contributes to the understanding of evil. As a consequence of

- the inevitable anarchy, and thus

- the inevitable struggle for power, and thus

- the inevitable selection for the ways of power, we get

- the brokenness of civilized societies shaped by the requirement for power,

- a requirement that imposes demands sometimes hostile (and in any event indifferent) to the needs and well-being of the human creature,

- demands that get internalized and thus put the human creature at war with itself.

This powerful impetus put the wave – the force that transmits the pattern of brokenness – into motion.

As the list above suggests, the matter of the initial impetus must be seen together with the ways that the wave gets transmitted through cultures over time. Together these two components will help reveal that central drama in the human story in which the force of wholeness contends with the force of brokenness to shape the human world.

Cry the Benighted Country

The mention of that “central drama” in the human story provides an apt place to share with you the opening part of a piece, written in 2015, bearing the title, “Cry the Benighted Country” (and the subtitle “What’s Gone Wrong in America”).

It was this piece I chose, after much thought, to be the op/ed for a purpose very important to me. My intent with this piece was to draw people in, wanting to check out my then just-published book, WHAT WE’RE UP AGAINST, to see what it had to say about our national crisis.

Here’s how that piece opens:

“Make America great again,” Trump [then just a Republican candidate] says. Not a bad idea, but first we need to understand what’s gone wrong.

In every society, both constructive and destructive forces are always at work. But the balance of power between those forces is not constant. Such factors as the quality of its leadership and the impact of its national experience can strengthen either the best or the worst in a society.

Consider, for example, the peoples of Great Britain and Germany at two points in the twentieth century.

In 1910, a time of relative stability before the outbreak of World War I, British society and culture might have been judged moderately healthier than the German—as a result of a somewhat more orderly history over the previous several centuries and of the more democratic structure of power in Britain. But the difference between them was not dramatic.

Thirty years later, the balance of power between the forces of light and darkness in the two nations had become starkly different. In Britain, the words of a new leader, Winston Churchill, summoned forth the best in the British people— their courage and their commitment to defend humane values.

In Germany, against which those values then needed to be defended, the leadership of Adolf Hitler was bringing forth the worst elements of German culture. While Churchill was inspiring his people to act heroically (in “their finest hour”), Hitler was turning many of his people into moral monsters — his “willing executioners.”

Many of us in America today sense an adverse shift in the balance of power between the elements that have made our nation great, and those that tear down what’s best about our nation. Some dimensions of this shift can be seen in three key elements of the American body politic.

(I’ll provide the rest of the piece later in this installment.)

What this story contrasting Britain and Germany suggests is that in civilized societies a battle goes on between two sets of forces. And in this battle, as in other battles, one side may play its cards more effectively than the other – or may be bolstered by the impact of happenstance — with the result that the balance of power between them shifts.

This power struggle between these opposing forces might reasonably be called “the battle between good and evil.”

Evil Defined

I expect that – from the various pieces of the picture I’ve presented in the course of this series –readers here have already been assembling in their minds how I’m conceiving of evil. But now seems like a good time for me to articulate more explicitly and systematically my answer to that first question at the beginning of this installment, “What is evil?”

(The following also works to answer “What is the force of the good?” They are analogous forces, working in somewhat similar ways, but working to take things in opposite directions.)

- We should think of “evil” as a force—meaning that it operates to move things within the system in a consistent and identifiable direction. (The same can be said of the force of the good, though the directions are opposite.)

- The direction toward which these forces move things—the consistency of their impact — has to do with the nature of the order each tends to produce.

In the case of evil, the force works to impart a pattern of “brokenness” to the things it touches. Imparting “a pattern of brokenness” means breaking down those orders that serve and enhance the quality of life in the system. The force of evil works, for example, to replace justice with injustice, integrity with duplicity, peace with strife, ecological health with ecological breakdown, etc.

The force of the good moves things in the opposite direction: where the force of evil destroys the order that enhances life, the force of the good builds and strengthens structures that serve life.

- Each of these forces—the good and the evil—works to expand its domain in the world. Whether brokenness or wholeness gains ground in the world is a function of the balance of power between the two forces at a given time, and that balance can shift depending on how well the two forces operate on the board on which they contend with each other.

- The force of evil has coherence. A dense network of interconnected causes and effects makes it coherent at any given time, so that the different elements of brokenness moving through the system are causally interconnected. That interconnection enables the different elements to reinforce one another, and allows the force to move through time in a coherent way.

(I have written, for example, that the force that drove the nation to civil war has returned in our times — by which I mean that so striking are the parallels between the characteristics and conduct of the GOP of recent years and those of the South during the 1850s, that we should recognize that what we see is a coherent pattern of brokenness that has managed to perpetuate itself through the generations. As in the 1850s, so also again in our times, that force has gained the power to wreak great destruction on the nation. To a meaningful extent, it is the same “It” that once propelled the United States into a nightmarish Civil War that now once again acts as a wrecking ball on the structures of wholeness of the nation.)

Again, the force of the good acts in the same way, except that what it spreads, as it works in a coherent way, through time, is a pattern of wholeness.

- The force of “evil” not only creates brokenness, but also exploits brokenness where it finds it in the human system. The forms of brokenness it exploits range from the anarchy in the intersocietal system, to unjust systems in civilized societies, to a lack of integration (or reconciliation, or harmony) among the elements of the psyche and character of human beings (individually and collectively).

The good operates similarly, but in the opposite direction.

As evil utilizes brokenness in the human system to expand its influence, the good utilizes “wholeness” (life-serving order) in the human system to increase the wholeness of the human world.

- When evil manifests itself in the world through the concrete actions of human beings –i.e. when it “wears a human face” – it displays those human qualities that have historically been associated with evil (in our religious traditions) – qualities like cruelty, deceit, greed, selfishness, and a lust for power.

With the good, the symmetry continues—i.e. same general structure of operation, but with the opposite sorts of human traits—with kindness instead of cruelty, honesty instead of deceptiveness, etc.—being visible in its workings.

In subsequent installments, as I indicated, I will be showing more about how these forces operate in their “effort” to shape the human world according to the “values” embedded in the patterns at their heart.

It is a picture that displays the profound interconnectedness woven by the play of cause and effect into our riven human world.

It is a picture that captures the tragedy and the agony of a creature caught between two (often-opposing) evolutionary processes: biological evolution (which consistently chooses life over death, and which naturally tends to align a creature’s experiential fulfillment with what has served ancestral survival) and the evolution of civilization (which has mandated that the demands of power be met, whatever the experiential costs for the human creature).

The Adverse Shift in the Balance of Power Between Good and Evil in America

But for now, let us look more narrowly at the opposing forces of wholeness and brokenness in America today. Many of us would agree, by now, that the nation faces a crisis. I believe this crisis can be best understood in terms of there having been in recent decades an adverse shift in the balance of power between the forces “good and evil” in United States.

As was said earlier, each of the forces – of wholeness and of brokenness – works to expand how much of its imprint it can leave on the human world, working to change the good to the evil, or to displace the evil with the good. They compete on the board of civilized systems as if engaged in some great spiritual game of Go. As in Go (or in chess) each is stopped only by the counter-vailing force of the other.

But the balance of power between the two forces can shift in any given system. (That’s what the earlier comparison of Britain and Germany – 1910 and then 1940 – was intended to illustrated.) Depending on how well the opposing sides are engaging in that battle, any civilized system can go through times of hopefulness and construction, and times of despair and deterioration.

Here, to offer one quick version of how it is that, in the America of these times, the balance of power has shifted toward brokenness, is the concluding half of that piece quoted earlier, “Cry the Benighted Country.” The earlier passage concluded with the sentence: “Some dimensions of this shift can be seen in three key elements of the American body politic.” And then the piece goes on:

First, Liberal America: taken as a whole, Liberal America seems to have lost its ability to convey its values in an inspiring way. If one compares what we have heard from recent Democratic leaders with the words FDR spoke to the nation – words captured in his great 1940 “I see an America” speech, and those words engraved in the granite of the FDR memorial in Washington — the change seems unmistakable. The moral and spiritual passion has largely been drained from Liberal America, weakening the power of its values to shape our society.

(The Pope’s recent [2015] speech to Congress provides another demonstration of how liberal values – compassionate concern for the well-being of all, and cooperation for the common good – can be articulated with power and resonance.)

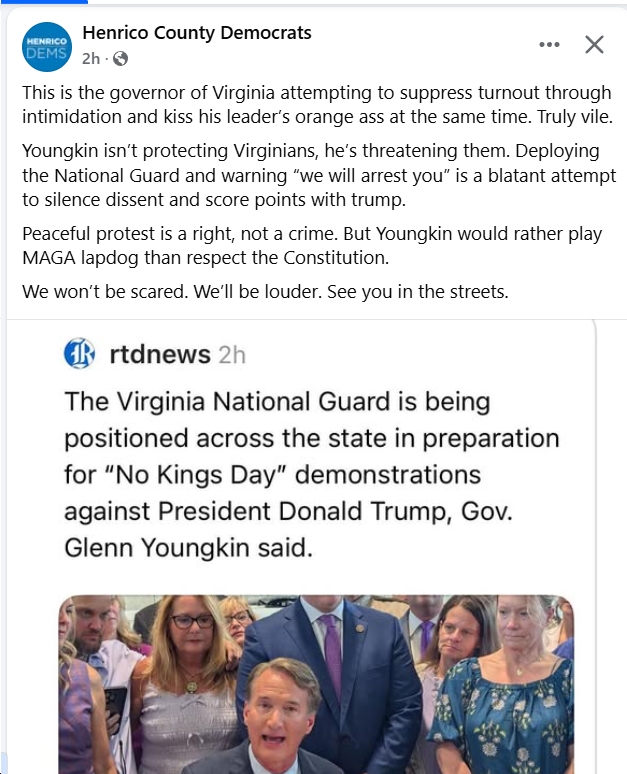

When it comes to the political right, who among us — not captive inside its propaganda bubble — can fail to see what a destructive force has taken over the once-honorable Republican Party?

One would be hard put to find, from the past fifteen years, instances of that party’s actions that have improved rather than damaged America. Among the hundreds of talking points that Republicans have injected into our national conversation, one would also be hard put to find many that have been more truthful than deceptive.

It is here we have paid the greatest price for Liberal America’s loss of moral and spiritual passion. The response from the liberal quarter to the rise of this destructive force on the right has been woefully inadequate.

This combination of the destructiveness of the right and the weakness of the left has resulted in one of the most profound crises in American history. [Note: this was written before the Trump presidency threatened.]

It is a time when, as the poet Yeats said, “the best lack all conviction, while the worst / are filled with a passionate intensity.” A time when, as a result, the lie has too often defeated the truth. [Note: this “passionate intensity” gap has fortunately closed since the election of Trump.]

This bring us to the press, whose essential job is to tell us the truths we need to know in order to function as competent citizens.

For more than a decade, we have been living through of one of the most politically dangerous periods in American history:

- an extraordinary presidential assault on the rule of law (2001-09), including the torture memos, which provide a template any future president can use to break any law with impunity;

- a massive transfer of power from the people to Big Money, aided by Supreme Court justices willing to sweep away precedent and contort the Constitution to bolster the power of the corporate system;

- the deliberate sabotage of the government for political advantage by the opposition party, which refuses to do the people’s business in a determined campaign to obstruct the president, resulting in the least productive Congresses of modern times;

- the crippling of the nation’s ability to respond to the greatest challenge humankind has ever faced — climate disruption — by those who refuse to heed the most urgent warnings ever issued by the scientific community.

All these unprecedented and degraded political developments are manifestations of the same coherent, destructive force damaging the nation.

Yet much of the press on which our citizens rely for their understanding of events, has hardly noted how extraordinary and dangerous these times are. The unprecedented has been treated as normal, the scandalous as acceptable.

It was not always thus in America. Our nation was once a beacon to the world, and could be again — but only if we can recognize, understand, and reverse the shift in the balance between the constructive and destructive forces at work in our nation.

Patterns of wholeness and brokenness are continually being transmitted through civilized systems. Truth-telling versus the lie. The drive for justice (embodied in values and institutions) verses the drive to take more than one’s share (embodied in the structures organized by the logic of the maximization of wealth and power as well as in the psychic structure of individuals). The nurturing power of love versus the injurious dynamics of indifference and cruelty. Etc.

Each set of patterns is integrated within itself, and each set requires effective work to maintain and extend their power within the human system.

(Though “each set of patterns is integrated within itself,” nonetheless each entity—whether individuals or organizations – is likely to be a mixture of elements of wholeness and brokenness.)

In the United States, over the past generation, we have witnessed the force of wholeness failing to maintain its previous strength, failing to defend what has been best about America, as the force of brokenness has waged a systematic and effective assault on the strong-holds of traditional American wholeness, whether it be in degrading the understanding of millions of Americans, or in undermining the rule of law and the constitutional order, or in diminishing the commitment to anything like “the common good” or “the good of the nation,” versus mere advantage for oneself and one’s side.

The picture of how these patterns compete to shape the human world is what I’ve been offering as “A Secular Understanding of ‘The Battle Between Good and Evil.’” And it is this picture that I will try to clarify further in the coming installments.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

NOTE: Do you want to follow this series? If so, please sign up for newsletter here to be informed whenever a new entry in this series is posted.

Are there people you know who would answer “yes” to the question with which this piece began? If so, please send them the link to this piece.

XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX

NOTE: The comments that follow, below, are from people I’ve asked to serve as my “co-creators” on this project, i.e. to help me make this series as good and effective as possible.

They are people who have known me and my work. And my request of them is that –when the spirit moves them to contribute – they add what they believe will help this series fulfill its purpose and give the readers something of value. I’ve invited them to tell the readers what they think will serve the readers well, and to pose questions or challenges they believe might elicit from me what I should be saying to the readers next.

I am grateful for their attempting to help me find the right path.

****************************

Forest Jones:

I like this piece for many reasons. I have read and agreed with many of these ideas of yours in the past.

In my discussions with liberal friends since the election of Trump, I continue to hear disbelief and confusion about how this could have happened. They refuse to look disparagingly on their Republican voting neighbors. They cannot envision any evil in the mix. They can express disgust at how stupid it all seems, but stop there.

They have no understanding of the influence of Fox news, Rush Limbaugh, and the like. They have no idea that there has been a constant propaganda campaign being waged for decades. They can repeat the latest sound bite and wonder when people will come to their senses and act responsibly to create the society that they think they live in.

I particularly liked going back to your 2013 article, “An adverse shift in the balance“. One paragraph bears repeating over and over:

As genuine conservatives, my neighbors understand that traditions are there for a reason, and should be honored and respected. But today’s Republican leaders, who claim to be conservatives, trample America’s political traditions while directing their followers’ attention to a few issues of concern that don’t get in the way of their deeper agenda — transferring wealth and power from average Americans to those who already have the most.

Do you still consider the “deeper agenda” to be transferring wealth and power…”? I see this as a point that should gather a crowd of supporters.

Andy Schmookler:

Thank you, Forest.

About your “deeper agenda” question, this is what comes up for me to say.

When it comes to understanding something like “a destructive/evil force,” there are two levels that are operating. One of them – being at the concrete human level — we can readily understand. So at that level, we can talk about the Republicans and about the powerful people they serve (the wealthiest Americans, and especially those who run the corporate system).

At that level, yes: “transferring wealth and power from average Americans to those who already have the most” is probably a reasonably accurate way of describing the main agenda of that set of people as they act through the American political system.

But there’s another level, which is abstracted from these specific humans, but works through them. This level is more challenging for us to comprehend—but no less important for that. Indeed, I believe the human drama (generally, and specifically the crisis in America in our times), this other level – that of the “coherent force” that works to transmit a “pattern of brokenness” onto everything it touches – is the more important level.

In the context of such a force, giving more wealth to the already rich and more power to the already mighty is part of a more general “agenda”: making the world more broken. More broken in magnifying the power of the lie, in increasing the role of cruelty (instituting torture, electing a president who likes to humiliate people), destabilizing the earth’s climate, etc.

Of course, to speak of an “agenda” when it comes to such a force of brokenness is to personify something that is not a conscious being, like a person. “Evil” acts “as if” it has purposes. But, just as “biological evolution” does not have a “purpose” to favor life over death – it just does—so also the force of evil does not have an “agenda” to make the world more broken.

It just does.

**********************************

Fred Andrle:

Andy, you write: “Yet much of the press on which our citizens rely for their understanding of events, has hardly noted how extraordinary and dangerous these times are. The unprecedented has been treated as normal, the scandalous as acceptable.” I think that’s absolutely right. The press has for years been delinquent in reporting on and explaining these destructive attitudes and actions on the part of our public officials and in the body politic. Until now.

I’m happy to report that some of our principal news reporting organizations are calling out Trump and Republicans in Congress for their actions detrimental to us all. I cite especially the New York Times and the Washington Post. These newspapers are exposing politicians’ prevarications and their moral delinquency in their news reports, as well as in their opinion columns.

This kind of analysis in news writing is something new. In the past, it was mostly limited to editorials. I think the owners of these media outlets understand the danger to our republic of the Trump administration’s actions, and the actions of Republicans in Congress, from their attempt to repeal Obamacare without an adequate replacement. to their demagoguing on race and immigration issues, as well as their destructive repealing of environmental regulations.

And Democrats are also being called out. The Times’ Nicholas Kristof recently reported on U.S. complicity in Saudi Arabian war crimes in Yemen, where Saudi bombing has killed at least 4,000 civilians. That aiding and abetting began in the Obama administration and continues under Trump. The Democratic party is not innocent, not immune to the brokenness you reveal.

I know that few conservatives around the country will read these newspaper articles, but I think it’s still very important that these influential media outfits are setting the record straight. And kudos to opinion columnists Charles Blow –liberal, NY Times – and Jennifer Rubin – conservative, Washington Post – for repeatedly and aggressively detailing Trump’s manifest unfitness for the office of the presidency.

Andy Schmookler:

I certainly agree with your comment about the Press. All the main components of the American body politic have failed America over the past almost two decades. Back when GW Bush was president, I wrote a piece about the press utilizing, the Sherlock Holmes image, “The Dog that Didn’t Bark.” (And as I wrote in that passage from my piece “Cry the Benighted Country,” quoted in the piece above, “much of the press on which our citizens rely for their understanding of events, has hardly noted how extraordinary and dangerous these times are. The unprecedented has been treated as normal, the scandalous as acceptable.”)

Your bringing in the Democrats as you do raises a couple of thoughts in my mind.

1) At the specific level of the instance you cite – President Obama aligning in some ways with Saudi Arabia in the Yemeni war – you may well be right in calling this a manifestation of “brokenness.” But I would have to know more – about what all the considerations were that Obama had to weigh in making whatever was the decision he came to—before I could join you in condemning it as you do.

I imagine that you feel able to reach your judgment of Obama’s decision without such knowledge, knowing from our previous conversations something about your pacifistic moral commitments.

Which, if true, would highlight an important difference between the moral approaches you and I tend to take: yours being a commitment to exemplify intrinsic wholeness in each action (against war), mine being a commitment to consequences, i.e. try to foster greater overall wholeness in the world (where war is sometimes the most constructive option).

That’s an age-old dichotomy, and I think there’s a place for both approaches in the world.

2) The second point is at a wholly different level: You’re assertion is doubtless correct that, “The Democratic party is not innocent, not immune to the brokenness you reveal.” But I do not regard that even-handed point, even if true, an important one to make in this moment.

It seems to me that the challenge in our current crisis is to understand and act on the enormous asymmetry between the political parties. In terms of what most urgently needs to be done, the significant problem with the Democrats has been with the ways they’ve been too much the opposite of the Republicans, not too much like them.

As I often said back during Obama’s first term: “We have one party that makes a fight over everything, even if the good of the nation calls for cooperation; and we have another party that is unwilling to stand and fight over anything, even if the nation’s good requires that they stand and fight to protect the nation from the destructive force that’s taken over the other major American Party.”

It is the asymmetry, not the symmetry, between the parties, I have long strongly felt, that matters most now. One side has been consistently destructive, the other side consistently weak.

There is no other force in America but the Democratic Party that is in the arena where our national destiny gets decided, that can battle and defeat this Republican Party, so extraordinarily fully possessed by a force of brokenness.

So critiques of the Democrats are certainly possible. But I think striving for “even-handedness” now is not the virtue it sometimes is, but rather a distraction from the urgent task at hand: turning back the dark tide.

******************************************

Philip Kanellopoulos:

Your discussion of free will reminds me of the Buddhist concept of dependent arising. Our interdependence, in both being and doing, finds its metaphor in the god Indra’s mythical net, at each vertex of which is fixed a jewel, each jewel reflected in every other jewel, and each reflection being itself reflected endlessly.

Your description of the coherence of the forces of good and evil through human systems is truly brilliant. I’ll ponder it for years, working to integrate my own worldview with your encompassing insight.

At the moment, I’m trying to understand how your theory relates to what appears to have been a conscious decision by business interests in the 1970s to return to what we might call an earlier era of brokenness in the American system, before the various liberation movements of the mid-twentieth century, before the New Deal, before the Great Society. I’m referring specifically to Lewis Powell’s 1971 memorandum ‘Attack on the American Free Enterprise System’ and the Trilateral Commission’s 1975 report ‘The Crisis of Democracy: On the Governability of Democracies’ (describing an “excess of democracy”).

These were essentially blueprints for how business elites could reestablish control over increasingly unruly populations demanding a meddlesome voice in their own government. However noble the initial motivations, the steps described in those documents were essentially those taken by corporate interests that have come to dominate American politics in the twenty-first century, to the enrichment of the billionaire class and the return to earlier levels of inequality of wealth and power.

In other words, the forces of brokenness seem to have acted deliberately in direct response to the forces of wholeness. Is this significant? Similarly, how does all of this relate to Germany’s barbaric response to the economic burdens of the Treaty of Versailles?

Andy Schmookler:

I’m not sure if even the “initial motivations” behind the increasing corporate takeover of American democracy deserve to be called “noble.” The moral vision behind the notion that “All men are created equal” – that every human being is worthy of equal consideration, a notion that would have been quite radical in most civilized societies over the millennia – is incompatible with the idea that the most powerful actors in a society (like the corporate system) should take still more power for themselves.

So if we accept the moral validity of that vision of equality, then the endeavor of the corporate system to prevent a democratically-elected government from being a check on their power, and to turn it instead into an instrument of their power, should be seen as being from the outset an expression of the force of wholeness.

And yes, you’re right, Philip, in suggesting that this effort was indeed a response to the rising force of wholeness—namely to an effort to bring the workings of the market system under adequate regulation in service of the greater social and ecological whole.

(As you probably know, Philip, my book The Illusion of Choice is an extended argument to establish that while the market system is a marvelous tool, it has its considerable blind spots, and that for a society to be whole it has to find collective ways of correcting for the blind spots that grow out of that atomistic market system. In other words, Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” optimizes some things but must be supplemented by the hand of government to optimize some other absolutely crucial values to which the market is blind.)

Hence, by the 1990s and even into the present moment, the political power of the corporate system has successfully blocked for decades now the kind of action that must be taken by government decision-making to address the immense challenge posed by climate change.

The Republican Party – which is the main political instrument of that corporate system – is the only major political party in any advance nation that has denied the science and refused to facilitate action to address what many describe as the greatest crisis ever to beset humankind as a whole.

I might add one point that fits into the coming presentation of how brokenness cascades through a cultural system in shape-shifting ways. In my WHAT WE’RE UP AGAINST, I cite Robert Reich to bolster my belief that the moral culture of corporate America has deteriorated over the past 60 years. (See page 174.) Reich speaks of how, back in the 1950s, there was talk about “corporate statesmen,” who were concerned about the well-being of all the elements/actors in the situation. Whereas later, “Corporate statesmen were replaced by something more like corporate butchers…”

In other words, brokenness at the moral level fed a campaign to increase brokenness within the political system which, in turn, has brought forth a political force that is blocking efforts to halt our breaking the stability of earth’s climate system on which the integrity of the biosphere depends.

***************************************

David Spangler:

As always, Andy’s logic is impeccable. What is interesting–and disturbing–to me in my work is that we see the force of evil (rather than specific evil deeds) as one extreme pole or another of a spectrum: either it is an outdated, Medieval theological fantasy which we have outgrown in our scientific, technological, enlightened age, or it is a Being, a Devil, actively working to undermine and destroy God’s work and against whom we must wage war, a war which, ironically, perpetuates the very brokenness it seeks to defeat. Too often, the brokenness we do experience in our lives and in our world is often taken for granted and assumed to be normal. It can operate at a level of ordinariness that doesn’t trigger our internal alarms, though it may engender feelings of regret and a wish the world could be otherwise. We must learn to look more clearly and with greater attention if we are to see and name it.

What is most powerful to me about Andy’s presentation is the idea that evil is not inherently part of human nature, a core part of my own thought and teaching. We are working within a world structure that is itself struggling to restore balance and wholeness, and in this struggle, we can be allies to that wholeness rather than perpetuators of the brokenness. The work is one of creating wholeness–what I call holopoiesis–within us, between us, in our institutions and society, and in our relationships with nature. It’s an ongoing work, at times a difficult one but properly approached, a joyous one. It’s not the work of a warrior mentality but of an artist’s sensibility that can imagine, conceive, and passionately co-create the shapes of wholeness in ourselves and the world around us.

Andy Schmookler:

I like what you say here, David, about the work being “one of creating wholeness…within us, between us, in our institutions and society, and in our relationships with nature.” That is indeed the most beautiful part of the work we’re called upon to do.

When you say “It’s not the work of a warrior mentality,” I am wondering if you’re not including among the necessary tasks in the cause of wholeness the need sometimes to join “the battle” between the forces of wholeness and of brokenness. For, as I see it — for example in America in our times — the a vital part of the necessary work does call for the spirit of the warrior. That’s why I wrote my 2014-15 series, “Press the Battle.”

(I told earlier in this series of how wrenching it felt to me when, in 2004, I felt called away from the work of creating wholeness — a project I called “Mapping the Sacred,” as introduced by an essay/sermon titled “Our Pathways into Deep Meaning” — because of what I felt was the urgent need to call out the destructive force then ascendant in the American power system.)

****************************************

Karen Berlin:

I hope your vacation/reunion time in Seattle is renewing.

I agree with your six points, summarized as:

- Evil is a force

- Evil moves toward a pattern of brokenness

- Evil force works to expand its domain

- Evil force is coherent—different elements reinforce one another

- Force of evil exploits brokenness to expand its influence

- Human expression of evil is negative qualities/behavior

We have different interpretations as to the origin of the evil force, but no disagreement on its existence and features or how it works.

The question I look forward to having answered in future installments is how is the force of good leveraged/maximized to “win” over evil. Classic age old plot, I know, good versus evil, but what you have outlined well in this piece is that evil exists, grows, seizes dominion and power. The question to be answered then is how is it battled and how does “good” maintain its foothold in humanity.

Andy Schmookler:

I wish, Karen, I could promise you some great insight into “how is the force of good leveraged/maximized to ‘win’ over evil.” I am not sure if there are any important strategic propositions that would have general usefulness. More likely, different situations create different kinds of opportunities, which “the good” can seize with different kinds of moves.

A pope from Poland might instill some moral charisma into the Soviet Empire, with the eventual effect of dissolving a tyrannical system. A carpenter from Nazareth might preach a way of looking at value that is like a diametrical opposite of the spirit that arises out of the process described by “the parable of the tribes.” Two great war leaders – Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill – can find the moral rhetoric and the strategic smarts to free a large part of the world out from under the cruel boot of fascism.

As for me, my main suit is truth-telling. That turns out not to be as irresistibly powerful as the younger me thought it was. But it is still clearly an essential component of a strategy for the good. Else, why would “Satan” be so often characterized as “the Deceiver”?

As for “good” maintaining its foothold in humanity, I believe that it is inevitably part of our humanity, because the selective process that crafted us has instilled at least the fundamental rudiments of the good into our nature. More on “the good” below, here, in my response to Jack Miles’ comment.

************************************

Jack Miles:

- Let me begin with the problem of good. Given that here is so much evil in the world, why is there anything but evil? What explains the survival of good? #9 touches on this key question early in the section entitled “Follow the Pattern of Brokenness,” but the exposition changes when one begins at that point. Evil has no meaning apart from good. The core problem is their simultaneous presence in our lives.

- I would like to refine somewhat the discussion, at “The Problem of Evil” as rooted in the Western, mainly Christian understanding of God. I agree that God has been understood as both all-good and all-powerful for most of Western, Christian history and that this understanding has been the taproot of theodicy as an attempt to resolve the resulting problem of evil (as in all questions beginning “How could a good God…?) But here are a few refinements of that history.

- The God of the Tanakh or Old Testament is not all-powerful and all-good. It is he who created the serpent who tempted Adam and Eve into the sin that then led God to condemn them and all their descendants to lifetimes of hard labor, sexual misery, and then death. Was it not evil of God to do that? Why didn’t he at least warn them? And could he not have forgiven them rather than punishing them so severely? Rather than the classic problem of evil, this is a problem of good and evil at war in the divine character. Later, in the Book of Isaiah, God admits this:

I am Yahweh, and there is no other,

I form the light and I create the darkness,

I make well-being, and I create disaster,

I, Yahweh, do all these things. (Isaiah 45:6-7)

Jacob Milgrom, in the Jewish Publication Society Torah commentary (Book of Leviticus) observes that so long as a truly strict monotheism obtained in ancient Israel, God’s only opponent was his human creature and, for most of the Tanakh, Israel. God rages against Israel as if indeed they were his only problem.

- The conceptual possibility of an omnibenevolent supreme being in malevolent/benevolent world invites the postulation of a second, separate omni-malevolent force. In Genesis, the serpent is not Satan but by the first century CE, pre-Christian Jews were already identifying the serpent with Satan and dramatically enlarging his role in human history. Somewhere in the centuries between (exactly when is hard to say), the author of the Book of Job presented a Satan powerful enough to tempt Yahweh into torturing an innocent man as an experimental animal—just to see if he would remain faithful. A direction was clear: the damn-the-consequences, uncompromising monotheism of Isaiah was giving way by degrees to a kind of ditheism.

In the New Testament, written by first-century Jews, Satan is clearly a powerful figure, strong enough to tempt Jesus (God Incarnate) in the desert, strong enough for the demonic possession that occasions Jesus’ expelling of demons, and so forth. In popular Judaism from then on, Satan remains a figure. In rabbinical theology, as relatively distinct from popular Judaism, we begin to hear about yetzer hara’—a quasi-autonomous evil impulse. These tendencies in both Christianity and Judaism, as they diverge, foster an understanding of God as, yes, omnibenevolent but not omnipotent. More exactly, not immediately omnipotent: God will triumph in the end, yes, but not before then. In the long interim, human beings will be caught between God and his eschatologically doomed but still powerful demonic opponent.

This is the understanding that one sees even more clearly in the Qur’an, where God creates Adam, requires his angels to bow down before him, and when Iblis rebels, damns him to hell but grants him a reprieve until the end of time within which Iblis proclaims that he will beset humans with temptation from all sides. Adam has heard all this, and only then does God command him not to eat from the forbidden tree. So Adam, though he sins anyway, has been warned. He knows what he is up against.

- To the extent, then, that Satan or Iblis or yetser hara’ have been taken as real forces in history over the course of Western history (within which Jewish and Muslim influence has always been present, even when not acknowledged), God has been all-good but, as to the actual experience of humans, not effectively all-powerful. And to that extent, evil has been acknowledged as something real.

- With all this as background, one way for me to engage your overall endeavor is to see it as a search for what in theology would be called a “Satan-term”—that is, a source of evil, a personification or a hypostasis (to use another theological term) to which can be attributed all that is not To an extent, your effort takes good as a given and explains evil. I know: this is not entirely true, but the emphasis does fall roughly this way. You find a new source of evil, a new Satan-term, in an ineluctable historical process by which human evolution, despite the fact the essentially innocent human species has sought only to live and thrive, has nonetheless produced an environment within which humans conduct themselves in ways inimical to human survival and welfare. Conventional theodicy, seeking, in Milton’s famous phrase, “to justify the ways of God to men,” shows how over time God can draw good from all the evil that he “allows” in his world. Your reverse theodicy seeks to justify the ways of men to men—that is, to show how over time humans have drawn evil from good, albeit against their conscious intent. Your soteriological hope is they may be saved from themselves by a better human story that makes them better aware of how their actions have worked against their intent. This is the truth that will set them free, to quote the Gospel of John. You re-locate what in the Tanakh is an interior struggle of good and evil within the deity from the deity to humanity. Humanity’s goodness is saved; humanity’s evil is acknowledged but revealed as the unforeseen and unforeseeable consequences of evolution.

- Evolution here plays the role that chance played in various ancient cosmologies that were largely driven out by Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, though they began to return at the Renaissance. For these three, God providentially controls everything so that, conceptually, literally nothing is left to chance. But echoes of an alternative survive even in the Bible. In the Book of Ecclesiastes, though it never denies the existence of Yahweh, much remains left to chance:

I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all. (9:ll)

You are a man of wisdom, understanding, and skill, and yet bread, riches, and favor have not come your way. Why? Judaism, Christianity, and Islam would all answer, “It was the will of God.” Ecclesiastes would answer: “time and chance happeneth unto all, even you.” Ecclesiastes is the survival of a “pagan” cosmology within the Bible.

The kind of faith that engages time and chance as a key independent variable is faith in luck. Countless humans do have a kind of faith in, or trust in, luck. Others insist that luck has nothing to do with it: “you make your own luck” or “you make your own weather” or “you never give up” or whatever. A colder acknowledgment of the reality and true power of chance humbles you when life has been good to you and consoles you when it hasn’t been. As I write, Irma is ploughing into Florida, but remember the Indonesian tsunami? A quarter million dead within an hour, and what had they done to deserve it? A horrifying vision of the power of chance. Yet recognizing such power can also foster a forgiving spirit toward those who offend because they have been offended—like King Lear, “more sinn’d against than sinning.” Forgive them as you forgive yourself.

- In the short term of American electoral cycles and on the small stage of the United States, a path forward out of the current political and moral morass might begin with a set of candidates, even a party, that acknowledged all the hurt “out there,” perhaps even acknowledging the hurt that lies behind some of the white hatred. Start there, continue with an admission of humility (good government can do something about this for you, even good government can’t do everything), and on from there.

Andy Schmookler:

As usual, Jack, you offer much that’s thought-provoking

I’ll address myself to two things in your comment, and they unfold one into the other.

First, about the reconceptualizing of God as a solution to understanding the problem of evil. You write about this reconceptualization : “Rather than the classic problem of evil, this is a problem of good and evil at war in the divine character.”

My response to that is, where does it get you?

One has hypothesized a God, the belief in which is not much tied to evidence. (It’s a hypothesis for which I have wanted to find evidence, but cannot see in the way the world has unfolded good grounds for such belief.)

And the original puzzle has not been solved but only transferred to new ground, asking about this Being who might or might not exist: why would this divine character be divided in that way?

I don’t see that as making progress toward explaining what we find in the world, which includes so much brokenness.

How much better to understand the problem in a way that rests firmly on the evidence and on what logic says that this evidence shows.

My “integrative vision,” to be specific, lays out a sensible way of interpreting what’s happened to our species that builds upon what science has told us about the evolutionary process, and it shows how that view of life brings into focus how dangerous it was for this cultural animal to break out of the biological order with the creation of civilization.

That “vision” offers nothing to explain how it comes to be that there is such a universe as the one we live in, or about why it is ordered in the particular way that it is, in terms of structure and the laws governing it.

But once we have the system existing and running, the problem of evil can be explained in a seamless unfolding of the story of life emerging on this planet, leading eventually to life’s embarking (with our species) on a wholly new experiment, which inevitably plunged the world of the civilization-inventing animal into a cascade of brokenness.

Voila: Evil explained.

(Coming installments will detail the mechanisms by which that brokenness can cascade in ways that show the face of evil that’s buried within the human world—a cascade that involves shape-shifting flows of the spirit of brokenness: Now it is war, now it is tyranny, now it is injustice or exploitation or evil or deceit or cruelty or hypocrisy or the lust for power or the insistence on strife or the degradation of the natural systems on which we still depend for our survival.

All these, different forms of brokenness that get pushed along by a destructive force.

So I claim that the view of things I am presenting here – in contrast with one that makes what seem like unsubstantiated assertions about the existence and nature of a Deity — presents a highly plausible explanation that draws upon humankind has come to know about how things develop.

It is in that context that I want to respond to a second part of your comment: namely, your initial comments about the good –“ Given that here is so much evil in the world, why is there anything but evil? What explains the survival of good?” – the implication of which, I thought, was that though I was talking about evil I had neglected to deal with “the good.”

I actually began this series with the good. After an introductory entry, I turned to writing two pieces, # 2– How “the Good” Emerges Out of Evolution

Followed by # 3– The Sacred Space of Lovers

In those two entries, I presented “the good” in a way that, once again, makes sense in terms of what science has told us about the nature of the evolutionary process that has shaped us.

That argument begins with defining the good in terms of the quality of the experience of creatures to whom things matter. I argue that basing the idea of “the good” on the quality of experience of sentient creatures is the only way it makes irrefutable sense to declare that one thing is better than another: we sentient creatures experience of the betterness of those things that fulfill us than those things that injure us.

And I argue that such value—value that registers experientially — emerges out of an evolutionary process that begins by choosing life over death, that goes on to create creatures who experience things positively or negatively in accordance with how such things have borne on the matter of survival for the creature’s kind. And that therefore we tend to experience as good – as beautiful, as right, as whole, even as sacred – those things that have ancestrally been life-serving.

Life goes in for Wholeness, and has done so also in crafting our human nature. (Thus, in answer to your question about “What explains the survival of the good?” so long as human lives come into the world bearing our biologically evolved nature, there will be a force leading us toward that experiential fulfillment that constitutes the good.)

Hence, that epitome of human fulfillment, discussed in # 3, which I call “The Sacred Space of Lovers.”

The explanation of evil is but one component – albeit one which our times have made it essential to see — of a unified story. This story is consistent with science, which means it is founded on evidence. And it is careful in its logic.

The same evolutionary perspective that provides a clear view of “the good” also shows that there is something in the human world that acts in ways that are quite similar to what traditionally has been called “evil.” This perspective can explain how that “force of evil” arose and what methods it uses to degrade the human world, breaking up what’s whole.

By “same evolutionary perspective,” I actually am grafting together two evolutionary processes, the process of biological evolution and the subsequent process of the evolution of civilization. The brokenness emerges out of the conflict between the two, but at the same time, as shown in entry’s #4 and #5), the second evolutionary process grows inevitably out of the first, if a creature takes the fateful steps out of its biologically evolved niche, as humankind did ten or so millennia ago.

So it is in that sense fundamentally a continuous process that creates a troublesome discontinuity, as a creature taking a step unprecedented in the unfolding story of life on earth inadvertently unleashes a process of disorder that has thrown turmoil into the system of life.

A new evolutionary process (described by “the parable of the tribes”), has introduced conflict and brokenness into the human world and the system of life. And the dynamics of that give rise to a force whose coherence can be seen, constituting what we are entirely justified in calling a “force of evil.”

How that “force of evil” works – moves through civilization as a “coherent” force imparting a “pattern of brokenness” – is what I intend to show in the coming entries of this series.

But there’s still the good, and the original life-oriented, fulfillment-seeking, wholeness-loving structure remains within us, waiting for us to harness it both to heal the world and to bring ourselves fulfillment.

Not that “the good” comes maximally realized within us, automatically, from nature. It needs to be developed. (More on that, later.)

But it is a component of our nature: it was crafted to lean toward the good, and it can be inspired to work toward the good. Part of the human task is to employ the in-built component of wholeness to develop wholeness further.

In other words, Tikkun Olam (Hebrew for “repairing the world”) is what happens to the extent that we can align ourselves with the wholeness that contains justice, compassion, honesty, love, peace-loving, and all those other things we rightly regard as good.

****************

Previous Entries: