By Josh Stanfield of Activate Virginia

A couple months ago, I got a call from a friend in Maryland asking me about divestment in Virginia. In Pennsylvania, Lehigh County Controller Mark Pinsley made the news with his plan to divest $145 million of the County’s money from Wells Fargo, since Wells Fargo supported anti-abortion politicians. The question to me: was there any analogous movement in Virginia against banks who supported anti-abortion politicians?

I did a little research, and while I didn’t find any divestment efforts in Virginia centering reproductive justice, there’s definitely been divestment activity on the fossil fuel front. This momentary research effort, however, ignited my curiosity about Virginia banking – and about our local elected treasurers.

Recent Fossil Fuel Divestment Efforts in Virginia

In 2015, a group of George Mason University professors (and three students) sent a letter to the presidents of both GMU and the GMU Foundation urging the university to fully divest from assets in fossil fuels. In 2019, the City of Charlottesville divested the city’s operating budget investments “from any entity involved in the production of fossil fuels or weapons.” And just last year, DivestUVA led a public campaign to demand that the University of Virginia divest from the fossil fuel industry.

There’ve also been recent shareholder divestment efforts aimed at Dominion Energy due to its natural gas holdings, and there’ve been divestment efforts aimed at banks that finance the proposed Mountain Valley Pipeline.

Last year – on the legislative front – Democratic Delegate Kaye Kory and State Senator Jeremy McPike introduced bills (HB645, SB213) that would require the Virginia Retirement System and local retirement systems divest from fossil fuel companies by 2027. Both of these bills failed miserably at the committee level, with only one member of the General Assembly – Democratic Delegate Sam Rasoul – supporting either bill with his vote. The Virginia Sierra Club supported these bills.

In this 2023 General Assembly session, Republican Senator Ryan McDougle has introduced SB1437 restricting “environmental, social, and governance investing” by the Virginia Retirement System – perhaps a move in the opposite direction of the Kory-McPike efforts last year. This bill is co-patroned by over half of the Virginia Senate Republican Caucus and is in line with efforts by ALEC and Republicans nationwide “to pass anti-divestment bills that would punish financial institutions that consider the climate crisis in their business deals or try to do something about it by not working with fossil fuel companies.”

So far, none of these Virginia fossil fuel divestment efforts seem to focus on the elected officials who can unilaterally divest county and city funds: the local treasurers.

Virginia’s Elected Treasurers

Article VII, Section 4 of the Constitution of Virginia provides for the elected treasurer in each county and city, one of the “constitutional officers”:

“There shall be elected by the qualified voters of each county and city a treasurer, a sheriff, an attorney for the Commonwealth, a clerk, who shall be clerk of the court in the office of which deeds are recorded, and a commissioner of revenue. The duties and compensation of such officers shall be prescribed by general law or special act.”

Virginia Code §15.2-1608 establishes a four-year term for the elected treasurers:

“The voters in every county and city shall elect a treasurer unless otherwise provided by general law or special act. The treasurer shall exercise all the powers conferred and perform all the duties imposed upon treasurers by law. He may perform such other duties, not inconsistent with his office, as the governing body may request. The treasurer shall pay from the funds of the local government all properly authorized accounts submitted to him for payment. He shall be elected as provided by general law for a term of four years.”

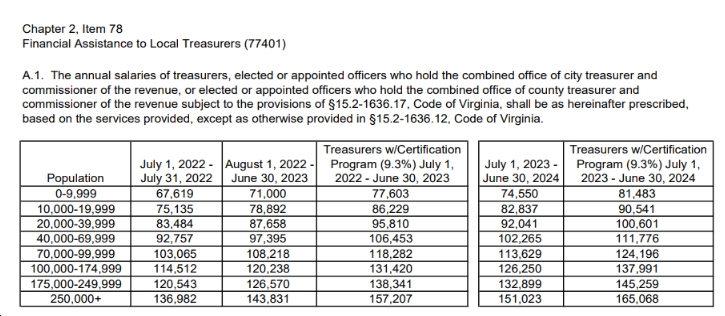

Their salaries are set by the Compensation Board:

The vast majority of elected treasurers run unopposed, and they run in the off years with members of the General Assembly. This year, the counties will elect their treasurers (except for Albemarle, Fairfax, Henrico, and Prince William which don’t elect their treasurers). In 2025, the city treasurers will be up for election.

The Treasurer’s Unique Power

Local treasurers have the unilateral power to change the banking institutions with which their locality banks and invests, such authority found in § 58.1-3149 of the Virginia Code:

“All money received by a treasurer for the account of either the Commonwealth or the treasurer’s county or city shall be deposited intact by the treasurer as promptly as practical after its receipt in a bank or savings institution authorized to act as depository therefor. All deposits made pursuant to this provision shall be made in the name of the treasurer’s county or city. The treasurer may designate any bank or savings and loan association authorized to act as a depository to receive any payments due to the county or city directly, either through a processing facility or through a branch office.”

The only caveat is that the treasurer must use a “qualified public depository” as defined in § 2.2-4401 of the Virginia Code thus:

“’Qualified public depository’ means any national banking association, federal savings and loan association or federal savings bank located in Virginia, any bank, trust company or savings institution organized under Virginia law, or any state bank or savings institution organized under the laws of another state located in Virginia authorized by the Treasury Board to hold public deposits according to this chapter.”

One county treasurer was kind enough to pass along a 2022 list of these qualified public depositories:

Where Do Virginia Localities Bank?

Out of curiosity, I individually contacted every elected and appointed treasurer in Virginia; so far, I’ve received responses from over 90% of them. I asked these treasurers which banks their county, city, or town uses for deposits and investments. I also asked if there were existing contracts with these banking institutions and, if so, for the date the contract ends. You can find all of that info here or in the spreadsheet below:

Out of 143 Virginia localities listed, and based on over 90% of localities reporting, the following banks were the top banks for deposits:

Truist (via BB&T and SunTrust merger): 29% of Virginia localities

Wells Fargo: 16% of Virginia localities

Atlantic Union Bank: 9% of Virginia localities

Bank of America: 7% of Virginia localities

United Bank: 5% of Virginia localities

First Bank & Trust: 5% of Virginia localities

In terms of investments, localities rely heavily on the Local Government Investment Pool (LGIP), the Virginia Investment Pool (VIP), and to a lesser extent the Virginia State Non-Arbitrage Program (SNAP). The following were the top investment institutions reported by over 90% of localities:

LGIP: 29% of Virginia localities

VIP: 17% of Virginia localities

Truist (via BB&T and SunTrust merger): 4% of Virginia localities

PFM Asset Management: 4% of Virginia localities

Atlantic Union Bank: 3% of Virginia localities

SNAP: 3% of Virginia localities

Approximately 50% of localities have contracts in place with banking institutions for deposit/investment services, although some treasurers told me they consider a contract in itself an infringement on the treasurer’s right to unilaterally change banking institutions at will.

Banks with Fossil Fuel Entanglements

The Banking on Climate Chaos 2022 Report – a report endorsed by dozens of prominent environmental groups across the globe – details and analyzes global financing for the fossil fuel sector by banks.

Although this report represents just one list of banks with fossil fuel entanglements, let’s consider the so-called “Dirty Dozen,” the “top 12 banks financing fossil fuels globally, 2016-2021:” JPMorgan Chase, Citi, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, RBC, MUFG, Barclays, Mizuho, Scotiabank, BNP Paribas, TD, and Morgan Stanley.

Of those banks, Wells Fargo, Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, and TD Bank are used by some Virginia localities for deposits or investments.

These localities use Wells Fargo for either deposits or investments: Appomattox County, Arlington County, Charlotte County, Chesapeake, Chesterfield County, Town of Culpeper, Culpeper County, Fluvanna County, Galax, Goochland County, Halifax County, Hanover County, Loudoun County, Lynchburg, Madison County, Newport News, Orange County, Prince William County, Richmond, Roanoke, Rockbridge County, Salem, Stafford County.

These localities use Bank of America for either deposits or investments: Albemarle County, Chesapeake, Fairfax County, Isle of Wight County, Louisa County, Newport News, Norfolk, Portsmouth, Suffolk, Virginia Beach.

This locality uses JPMorgan Chase for either deposits or investments: Fairfax City.

These localities use TD Bank for either deposits or investments: Fairfax City, Manassas.

Potential Reform

Even if we use the admittedly truncated 2022 Banking on Climate Chaos Report list of problematic banks, there’s potential divestment work to be done in convincing local Virginia treasurers to move the city/county/town monies out of banks with fossil fuel entanglements.

For those citizens who care about this issue, in Virginia, you’re in luck: the vast majority of treasurers are elected, which means (at least in theory) they’re supposed to be responsive to their constituents. As with all attempts to lobby your representatives, you never know if you’ll be successful.

But at the same time, any constituent who isn’t happy with their treasurer could always run for the office or run a candidate they prefer – and if they live in a Virginia county, they could start collecting 125 petition signatures right now.