by A Siegel

Last week, a broad environmental coalition and multiple Virginia state legislators coalesced for the announcement of the “Virginia Clean Economy Act” (VCEA). When one sees strong environmental organizations like CCAN, and its climate hawk founder/director Mike Tidwell, pushing hard to build momentum for the VCEA, the presumption has to be that this is serious action that would put Virginia well on the path to doing what is possible and necessary for the Commonwealth to do to address the climate crisis. But is it?

Compared to what had been possible when fossil-foolish, climate-science denying Virginia Republicans controlled the legislature, there is no question that this Act’s objective to have a 100% clean power system by 2050 (with an interim 60% by 2036) is a breath of fresh air.

While many aspects of (and certainly the intent of many promoting) the legislation merit praise, what appear to be unambitious targets have caused grassroots environmental activists and energy wonks to scratch their heads, asking why the objectives and requirements weren’t (far) more ambitious. There are more than a few folks who are head-scratching right now, trying to figure out “what is going on here,” and wondering “is there something that we’re missing?”

For starters, a simple back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that, operating merely on autopilot/”business-as-usual” (BAU), without any new legislation, would get Virginia pretty much to the ballpark of 60 percent clean electrons by 2030 (compared to the 60% goal by 2036 in the VCEA). This would occur due to already announced clean electricity projects – such as Dominion’s September 2019 announcement of a 2.6 gigawatt offshore wind project and Fairfax County’s November 2019 announcement of more than 100 rooftop solar installations, with intent to add more projects – plus reasonable suppositions as to what the market will naturally do, as a result of the continuing steep declines in wind and solar power prices.

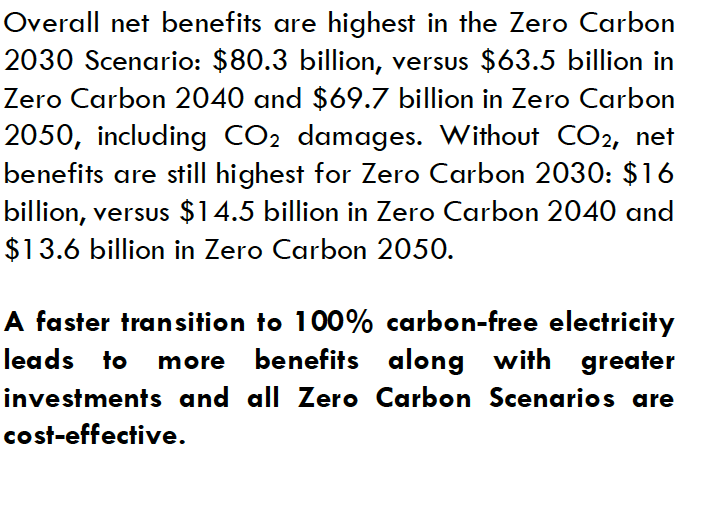

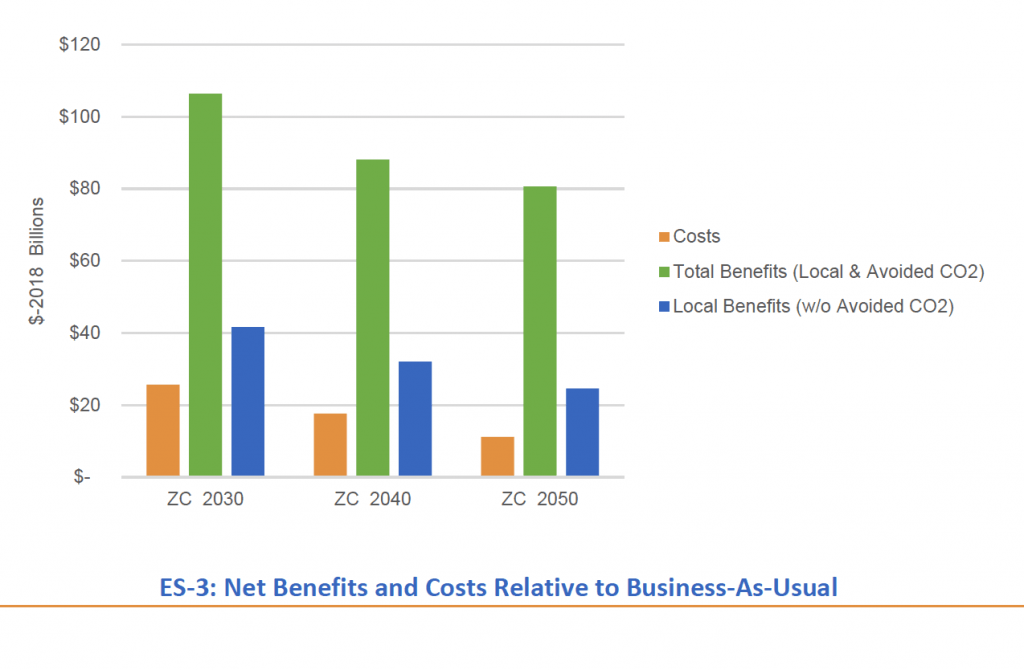

Asking around as to “how were the core targets in the VCEA reached,” a number of people referenced “Virginia’s Energy Transition: Charting the Benefits and Tradeoffs of Virginia’s Transition to a 100% Clean Grid” (pdf). Published in September 2019 by Advanced Energy Economy, which played a major role in developing the VCEA, this report provides a detailed analytical look at the requirements for and payoffs from achieving a 100% clean power sector by 2030, 2040, or 2050. In all three cases (see screenshot, below), the report team’s analysis makes clear that Virginia and Virginia electricity ratepayers would do far (FAR) better with moving to a zero-carbon system rather than remaining on a fossil-foolish BAU path. While analysis shows that the largest total benefits would occur from the most aggressive path (Zero Carbon 2030), the report concludes that this would drive up near-term homeowner costs and thus leads to a conclusion that a slower path would work better politically even if the full benefit streams would not be as high.

Another problem: the AEE report may have fostered misunderstandings that helped drive an unambitious approach in developing the VCEA. Here are three issues along with potential implications from them.

Remaining Stove-Piped and Not Proposing Ways to Solve Logjams

The AEE analysis concludes that acting to achieve the 2030 zero-carbon target would drive up household electricity bills in the mid-2020s and leave homeowners without total electricity savings until almost 2040 (due largely to higher capital investment requirements, both for new clean electricity production and for paying off early retired fossil fuel systems). If true, this would provide a polemical debate point for those seeking to prevent rapid moves to a clean power system. That’s unfortunate.

What the study does not provide, perhaps due to a limited charter to the analytical team, is options for addressing (eliminating or, at least, ameliorating) this issue. For example, the benefits of the clean electrons will accrue not just to power users. We will all have cleaner air to breath. There will be fewer adverse health outcomes. There will be more and higher-paying jobs. Money will stay within the Commonwealth rather than paying for imported fossil fuels. The Commonwealth will have more tax revenues.

Hmmm…think about that last in the context of a desire to moderate (or eliminate) a short period of higher utility bills. Couldn’t a portion of the additional revenues be used to eliminate that identified early cost hit? Perhaps, for example, the Commonwealth could provide borrowing authority so that renewable energy projects would have lower interest and longer term loans? In sum, the analysis identified a subset problem within the highest value total solution set. But rather than identifying paths to address that problem, the report devolves to a sub-optimal overall solution – delaying the transition to 100% clean energy by many years – to avoid the problem.

Using rejected Dominion Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) as key source

Long ago, an econometrics professor (who headed, btw, the CIA’s econometrics team) pounded into me the importance to reading, following, and asking questions of study footnotes. In wondering about this report’s conclusions, and in looking at its footnotes, Appendix A’s Footnote 1 seemed sort of odd.

Footnote 1 refers to Dominion’s 2018 Integrated Resource Plan, which Dominion submitted to the State Corporation Commission (SCC) for review in May 2018. If one were totally unfamiliar with the Commonwealth’s energy situation and interactions with Dominion, this might seem like a perfectly reasonable basis for doing analysis and planning. After all, Dominion provides the majority of the Commonwealth’s electricity; the IRP is the required reporting about what Dominion sees over the coming 15 years; and it is pretty much the most detailed data set that Dominion puts out to the public regarding Virginia’s future electricity supply and demand.

Of course, those who closely follow Virginia energy policy would be well aware that this report was highly unusual in Commonwealth history. In fact, in December 2018, the SCC rejected the IRP due to significant disagreements with Dominion’s future forecast for Virginia electricity demand.

As one critic put it in May 2018:

Dominion continually insists on using outdated modeling practices to predict future electricity demand, and it doubles down on this error by proposing to satisfy that demand in a non-economic fashion. This approach marginalizes lower-cost options like energy efficiency and solar in favor of expensive, company-owned, customer-financed natural gas infrastructure—an approach that will force unnecessary costs on customers while allowing Dominion to earn high rates of returns to the benefit of its shareholders.

The SCC ordered Dominion to rework elements of its IRP. Dominion returned in March 2019 with a significantly lower (though almost certainly still exaggerated) forecast for future electricity demand in Dominion territory. As far as can be determined (and after having sent requests to multiple people seeking to confirm this without, as of this writing, any response), the report relied on the May 2018 IRP’s highly inflated forecasts of electricity demand – rather than using the somewhat less inflated March 2019 numbers.

Basing requirements planning on a [MUCH] higher total makes bridging the gap between today’s roughly 39 percent clean power and a 60%-by-2036/100%-by-2050 clean power system much -MUCH – more difficult. [Note: Having far from adequately analyzed this, this higher total would appear to drive a requirement for many gigawatts (GWs) of additional clean electricity capacity and quite likely above 10 GWs.]

If, as seems to be the case, this report relied on the rejected March 2018 IRP for its projection of future Virginia electricity demand, then it started from a (far) more pessimistic starting point than reasonable.

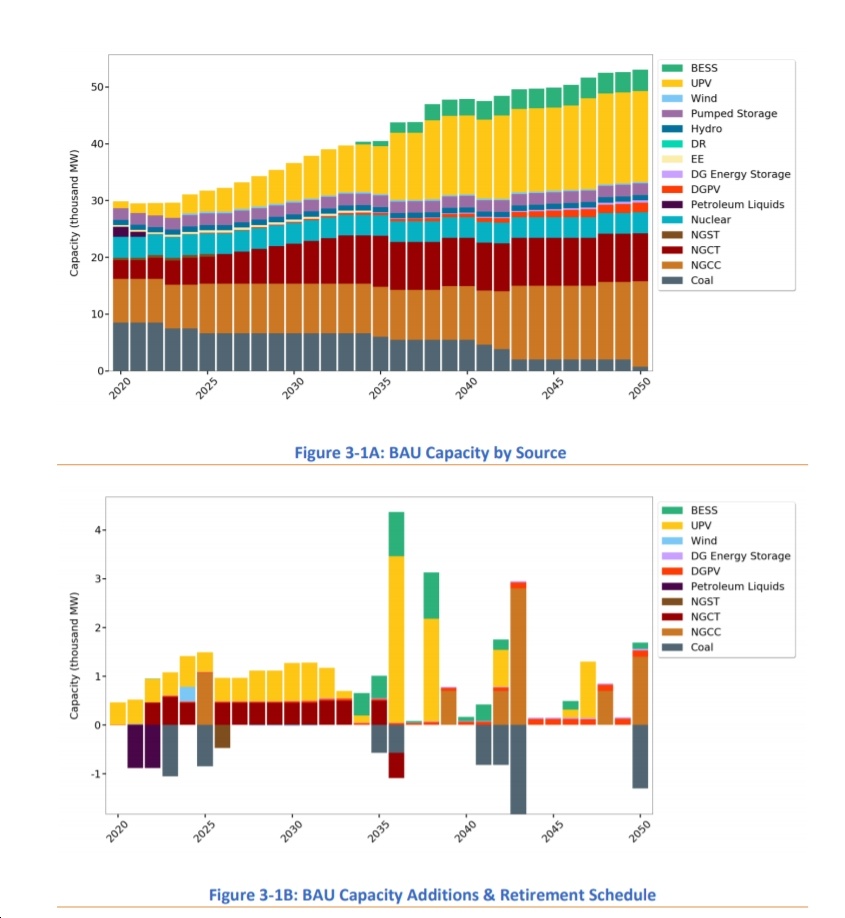

OBE means overtaken by events

Of course, conducting analysis and writing a substantive report can take real resources and time. They certainly can’t be done overnight. And, real-world events can make a report overtaken by events (OBE) even before it is printed. This report was released in September 2019. What also happened in September 2019? Dominion’s announcement of plans for 2.6 gigawatts of offshore wind to be installed and operating before the end of 2026. As of September 2019, therefore, a major portion (roughly 10 percent) of current Virginia electricity annual demand will be met by offshore wind power by 2026. As this is an announced plan, that should make it part of business as usual (BAU) forecasting. And yet, understandably due to OBE, this major offshore wind project (along with other recent clean energy announcements) isn’t reflected in the AEE report (neither in the BAU case nor is there serious wind resources (not an OBE issue but a choice (erroneous in my opinion) not to do so) included in any of the paths for creating a clean power economy).

Further dissection might reveal

The above are just a few points from an initial, cursory look at the report. It might well be that more detailed dissection would reveal additional ways in which this report provides a (highly) pessimistic basis for planning a Virginia Clean Economy…and for designing legislation to get us there.

![Video: Sen. Mark Warner Says He’s “concerned that [the Trump administration] may try out some of their [voter suppression] tactics” in the VA Redistricting Referendum in April](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/warner0212-100x75.jpg)