From The Commonwealth Institute:

Budget Matters: A Brief Look at Spending Choices by Virginia on Policing

The struggles for racial justice and economic justice are deeply intertwined. For too many residents of Virginia, particularly Black and Latinx folks, racial profiling in policing and the over-policing of their neighborhoods leads to stressful, expensive, and sometimes life-threatening encounters with law enforcement, courts, and jails. These encounters happen more often in Black communities and, even in cases with less serious charges, often leave individuals and families worse off financially due to factors such as lost jobs, pretrial bail costs or fees for pretrial supervision, and court fines and fees. They also lead to a loss of public safety as many Black and Latinx people fear police and court involvement just for moving around in public spaces, with all the immediate and long-term harm that those interactions can carry.

In 2019, TCI began exploring with partner organizations how we could help reduce both the criminalization of low-income communities of color and the impact of criminalization on the financial health of families and communities of color in Virginia. In January, we hired a senior policy fellow and counsel to lead this work. Although much of this work is still in the research and community listening phases, this blog post aims to provide what information we can to advance the conversation in the current moment, within our area of expertise.

In response to the most recent round of killings of Black people by police and vigilantes, protesters in cities around the country, including in Virginia, are demanding concrete policy changes. These demands include reforms to police procedures, civilian review boards with real power, and a defunding of police. In Richmond, many of these demands have been championed for years by Justice and Reformation for Marcus-David Peters and the Richmond Transparency and Accountability Project (RTAP), along with many other grassroots organizations such as the Virginia chapter of Southerners on New Ground. Nationally, the policy platform released in 2016 by Movement for Black Lives provides a good introduction to many of these policies.

TCI has no particular expertise in police procedures or civilian review boards, and we encourage people who want to learn more to review the resources linked above. We do have expertise in budget analysis.

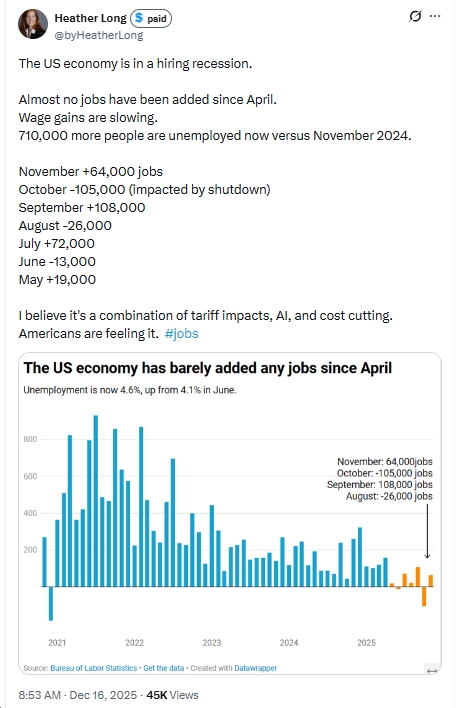

Spending on policing is often justified as a way to prevent or respond to violent crime, especially real or perceived increases in violent crime. Yet even as violent crime has dropped sharply, spending on law enforcement by local governments in Virginia has stayed high.

In 2006, local law enforcement budgets in Virginia totaled $1.4 billion. That doesn’t even count the cost of local jails and courts, and even so was more than local spending from all sources on mental health, public parks, and libraries.

Between 2006 and 2018, Virginia saw a 29.5% drop in violent crime. Logically, such a significant drop in violent crime should equate to a drop in police spending as well. However, law enforcement spending by Virginia cities, counties, and towns did not drop significantly. In 2018, statewide spending on police per capita, when adjusted for inflation, only decreased 0.3% compared to 12 years earlier, despite violent crime having dropped sharply. (This data includes spending by local governments on law and traffic enforcement, and includes spending from all funding sources, including grants from the state and federal government.)

Meanwhile, spending by the state of Virginia on the State Police rose sharply during this time period of 2006 to 2018, with general fund spending — the money over which state legislators have the most control — growing 22% and overall spending growing 17%. That’s in line with national trends, which show a substantial, almost constant increase in spending on policing since 1960, with almost no correlation between change in spending on policing and change in crime rates. This increased spending is not included in the local government data, since the State Police are a state agency.

Overall spending on the state and local level include federal grants for law enforcement but do not account for donations of military equipment. Through the federal 1033 Program, Virginian law enforcement received roughly $1.6 million worth of military equipment in 2018. These items included vehicles, radio equipment, and pepper spray. In previous years, Virginia law enforcement agencies also received hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of guns from the 1033 program.

During tough budget times like the current pandemic and resulting recession, Virginia’s cities, counties, and state have made cuts to services that help families and communities thrive, including strong K-12 schools. It’s no coincidence that many of these are services that are particularly important for Black and Latinx communities who are more likely to have been locked out of the economic opportunity that is needed to access private services when funding cuts weaken the public sector. Meanwhile, those same communities bear the brunt of over-policing and police brutality. Reallocating resources to invest in positive public services such as high-quality education, health care, and economic supports–and making sure Black and Latinx communities have equitable access–would go far to address the actual issues of public safety in the state, including freedom from the violence of poverty.

TCI is working to obtain the comparative reports on local spending for earlier years to provide a look at spending on policing in Virginia over a longer time period. We will also be continuing our current work on the impact of criminal fines and fees and pretrial detention on families, communities, and budgets across the commonwealth — since we realize that this state violence has a disproportionate impact on Black Lives.

— Laura Goren, Research Director and Gabriel Worthington, Research Intern

Print-friendly Version (pdf)

Learn more about The Commonwealth Institute at www.thecommonwealthinstitute.org

![Thursday News: “Europe draws red line on Greenland after a year of trying to pacify Trump”; “ICE Agent Kills Woman, DHS Tells Obvious, Insane Lies About It”; “Trump’s DOJ sued Virginia. Our attorney general surrendered”; “Political domino effect hits Alexandria as Sen. Ebbin [to resign] to join Spanberger administration”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/montage010826.jpg)