by Jon Sokolow

This is Part 1 of a two-part series. Part 2 will appear tomorrow in Blue Virginia.

The Commissioner of the Virginia Department of Health rejected the idea of conducting a thorough review of Mountain Valley Pipeline’s plan to bring thousands of out of state workers to a concentrated area of Southwest Virginia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, he directed staff to limit their efforts to providing “public health guidance” to MVP.

A lobbyist for Mountain Valley Pipeline expressed reservations about submitting its COVID-19 response plan because it might be made public under the Freedom of Information Act. He also dismissed concerns raised by Virginia legislators about MVP’s plan and apparently misled the Virginia Department of Health regarding the status of pending legislation that could stop construction.

And the lobbyist, using ties he had to the Governor’s office, sought VDH approval of MVP’s plan sight unseen in a Zoom meeting that included a company lawyer, VDH leadership and staff and a top official in the office of Virginia Governor Ralph Northam.

These are some of the troubling revelations contained in internal emails released by VDH in response to a Freedom of Information Act request. They are published here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and here exclusively for the first time. (References below are to these documents and include page numbers.)

A Pipeline to Nowhere

The Mountain Valley Pipeline is a $6.2 billion corporate boondoggle that would bring fracked methane gas from West Virginia to Virginia along a 300-mile route that includes mountainous terrain and the crossing of more than 1,000 rivers, streams and wetlands. It is intended to connect to an extension called MVP Southgate for which North Carolina has refused to issue a permit. The most expensive pipeline per mile ever conceived, MVP has been plagued by trouble since it was first proposed in 2014. Billions of dollars over budget and more than two years behind its original in service date, MVP was stopped from doing further construction in 2019 after multiple permits were lost as a result of legal challenges. Its certificate from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission is set to expire in mid-October. MVP has asked for a two-year extension and more than 43,000 people in Virginia and West Virginia have filed comments with FERC urging that the renewal be denied.

All for a climate busting pipeline that would produce the equivalent of 89 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually, as much as 26 coal plants or 19 million passenger cars.

Faced with a mountain of trouble – multiple lost permits, an organized opposition, tree sitters that have blocked the route for more than two years, an expiring FERC certificate, millions of dollars of fines for having violated Virginia environmental laws hundreds of times, a $104 million lawsuit by one of its contractors that seeks an order selling the pipeline for scrap, and new court challenges filed just this week – MVP looks very much like a boondoggle on its last legs. In fact, it looks a lot like the Atlantic Coast Pipeline did just before it was canceled on July 5.

But on July 15, barely a week after the ACP was canceled, the Trump Administration ordered an expedited review to restore MVP’s lost permits and get the project back on track. Those permits were just reissued and construction is likely to resume – for now.

Inaction by the Virginia Department of Health is now facilitating Trump’s rush to get MVP done

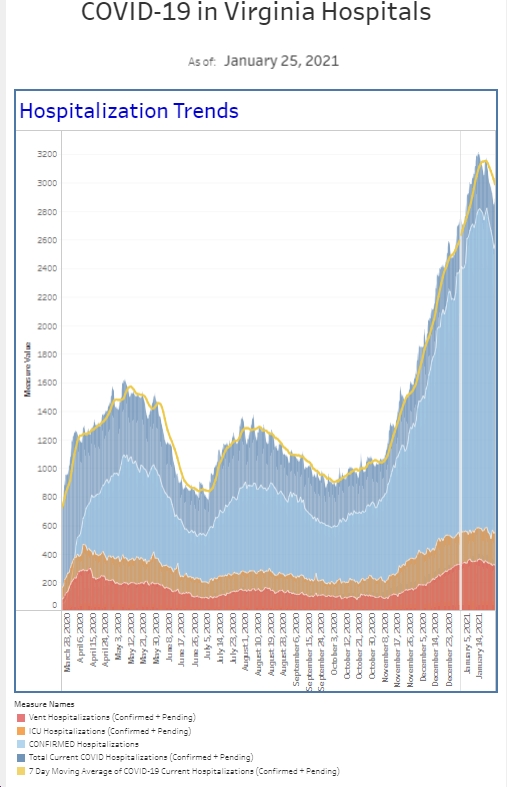

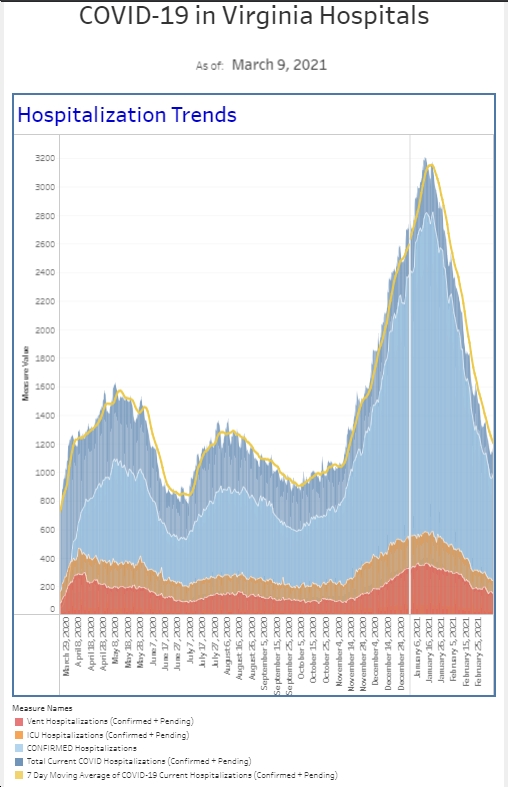

MVP announced in a May earnings call that it intended to bring more than 4,000 workers to a concentrated 30-mile area of Virginia and across the mountainous border in West Virginia once permits were reissued. This announcement fed concerns that bringing these out of state workers to Virginia in the middle of a pandemic created an unacceptable public health risk, particularly because the area of Southwest Virginia where they would be concentrated has limited health resources, only 100 intensive care unit beds and a population with a high rate of preexisting conditions that make them more vulnerable to the disease. In July, a group of health professionals called on Governor Northam and Virginia health officials to stop MVP from bringing in these workers during the pandemic. On August 6, 22 Virginia legislators led by Delegate Chris Hurst, whose district is along the MVP route, and Delegate Jennifer Carroll Foy, a candidate for Governor in 2021, asked Northam and the Virginia Department of Health to suspend work until the pandemic is over.

On August 20, Delegate Hurst introduced a bill that would require MVP to submit comprehensive safety and health plans to the Virginia Department of Labor and Industry and have those plans approved before being allowed to proceed. The bill was referred to a House committee and has yet to be docketed.

There is no record that the Virginia Department of Health ever met with or even spoke to those who have expressed alarm at MVP’s plans.

But when contacted by an MVP lobbyist over the past few weeks, the Virginia Department of Health sprang into action – to facilitate the company’s plan to resume construction.

In fact, VDH emails reveal that MVP’s corporate lobbyist, Rob Shinn, had direct and frequent access to top officials at VDH, all facilitated by the Governor’s office, where at least one high official, Marvin Figueroa, Deputy Secretary of Health and Human Resources, has a previous working relationship with Shinn. Figueroa would later participate in the Zoom call with MVP’s representatives.

This is a story about regulatory failure – or, more accurately, corporate capture of the regulatory process. And it is all happening now, in the middle of an increasingly threatening public health emergency and a developing and very real climate emergency.

A Lobbyist Who Fights “Determined Opposition”

Rob Shinn is a partner in Richmond lobbying firm Capital Results. He is just the sort of well-connected lobbyist an out of state fossil fuel company like MVP would want to deploy in such a situation. Not only does he have years of experience in Democratic campaigns, but his professional profile boasts that “[M]any of Rob’s projects involve helping clients solve challenging problems that require strategic planning and precise execution,” including “helping a client overcome determined opposition to build a new retail center” and “working to get government approvals to construct a major infrastructure project.” The latter is likely a reference to the Mountain Valley Pipeline, for which Shinn has been lobbying for more than five years.

On August 26, Shinn contacted Matt Mansell, Policy Director for Governor Northam. Mansell suggested he call VDH. Ellick 42.

Shinn’s next move was to call Jeff Stover, Executive Advisor to Virginia Department of Health Commissioner Norman Oliver. According to Stover’s account, Shinn’s call was about House Bill 5102, introduced the previous week by Delegate Hurst. Ellick 42. Stover immediately reported the conversation to two of VDH’s five Deputy Commissioners, Parham Jaberi (the Chief Deputy Commissioner) and Robert Hicks. Ellick 42. Stover said that Shinn was “working with folks at the Gov’s Office” and he suggested that a meeting be set up.

Stover told the two Deputy Commissioners that MVP’s lobbyist had told him that HB 5102 “was defeated.” In fact, HB 5102 had only been introduced on August 20, a week earlier, and had been referred to a House committee, where it was sitting. Ellick 41-42.

Deputy Commissioner Robert Hicks asked “if the bill was defeated, then why are we meeting.” He also asked if the Governor had a position on this. Ellick 41-42. That question was never answered – at least in writing.

Also on August 27, Shinn told VDH staff that MVP “will be re-starting work on the pipeline probably in the next month,” and that [t]here will be about 2,000 workers coming to Virginia between the re-start date and end of the year.” Ellick 40.

Then Shinn took a shot at the “determined opposition” he is paid to fight:

“There are a number of project opponents in the area that will no doubt raise concerns and issues related to the re-start of construction in an attempt to slow down the project.” Ellick 40 (emphasis added).

Not to worry, the lobbyist said. MVP “has developed a comprehensive COVID-19 preparedness plan” and the “governor’s office thought it would be a good idea to connect with you to review the plan and see if there are any additional measures we should consider.” Shinn said it “would also be good for the MVP people to connect with your local folk to sync up now, so we all have points of contact when people file complaints, etc.” (emphasis added). Ellick 40; Carr 1.

Translation: MVP and VDH should work together to be prepared when the “determined opposition” tries to use a public health emergency to file complaints about a public health threat.

A Health Commissioner Rolls Over

Later on August 27, yet another VDH Deputy Commissioner, Laurie Forlano, suggested that VDH’s role should be limited: “I don’t think it’s appropriate to comment on whether their plan is compliant with DOLI ETS” she wrote. Allan 2. That was a reference to Department of Labor and Industry Emergency Temporary Standards that were adopted by Virginia with great fanfare in July.

Forlano’s suggestion is stunning. When these workplace standards were announced, Governor Northam said that these “first in the nation standards…will protect Virginia workers.” The DOLI Commissioner added: “The Commonwealth’s new emergency workplace safety standards are a powerful tool in our toolbox for keeping Virginia workers safe and protected throughout this pandemic.” And the new standards apply to all workplaces in Virginia.

You would think it would be a wise use of taxpayer dollars for health officials to review MVP’s plan to bring thousands of out of state workers to Virginia.

You would think that a massive project that not only affects the workers themselves, but the communities in which they would live, eat, shop and congregate, should be carefully reviewed to see if it complies with these new groundbreaking regulations.

You would be wrong.

Instead of doing a full regulatory review of MVP’s plan – which as of August 27 no one had seen – Forlano said that she would be “happy to review it from a public health perspective, and meet with [MVP] if the Governor’s office would like us to.” (emphasis added). Allan 2.

Forlano also revealed something else that apparently has NEVER been made public until now: VDH’s “community mitigation team has responded to several inquiries from MVP throughout the pandemic.” (emphasis added). Allan 2.

Exactly what “inquiries” has MVP made to VDH “throughout the pandemic?”

Exactly how has VDH’s “community mitigation team” responded to these “inquiries?”

Has MVP already had infected workers along the route?

Because, even during the work stoppage, workers have been doing erosion and sediment control work. In fact, they have been photographed not social distancing and not wearing masks.

VDH may have some answers, but no one is talking – or even asking them, it seems.

(There are now reports that VDH itself has positive COVID-19 cases on multiple floors in its Richmond offices. But VDH is not talking about that either – and apparently no one is asking them. But that’s a story for another day.)

VDH Commissioner Norman Oliver immediately approved Forlano’s suggestion that VDH’s role be limited and quashed any idea that VDH would do a broad compliance review.

And that is when the dye was cast:

“Thanks, Laurie, for your comments! What Laurie raises is really the only thing VDH needs to address in this matter….We can continue to provide public health guidance, regarding the 2,000 guest workers coming to work on the MVP and the impact on the communities where this work will be taking place.” (emphasis added). Allan 1.

Commissioner Oliver’s directive that “public health guidance” – and not a review of MVP’s plan to determine whether it met strict state workplace COVID regulations – was “the only thing that VDH needs to address in this matter” set the stage for what ended up being a cursory review process that included MVP officials but no one from the community or health professionals outside of VDH.

The lobbyist, Rob Shinn, had succeeded in setting up a process in which MVP had exclusive access to Virginia Department of Health officials who agreed to not do a full review of MVP’s COVID-19 response plan. The “determined opposition” that the lobbyist is paid to defeat – which includes tens of thousands of taxpayers who pay the salaries of everyone at VDH, as well as elected officials representing many more people – were not included in these discussions.

MVP would not even agree to release a copy of its plan.

Instead, MVP and VDH agreed to hold a private Zoom meeting.

Has MVP disclosed its plans yet?

What happened at that secret Zoom meeting?

Stay tuned for Part 2 of this series.