by Kellen Squire

The two years that my colleagues and I in emergency services were battered by the acute stage of the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded like a runaway freight train jumping the tracks. You could see it coming, couldn’t do anything to stop it, and every time you thought it was going to stop… it only got worse.

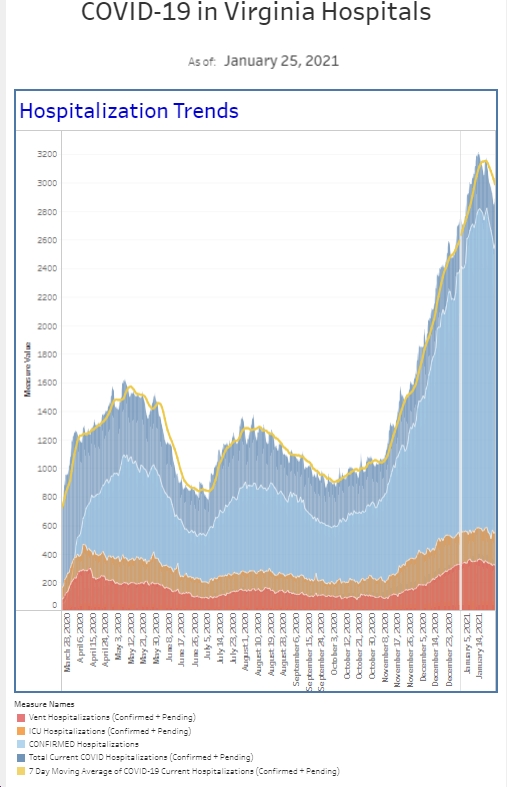

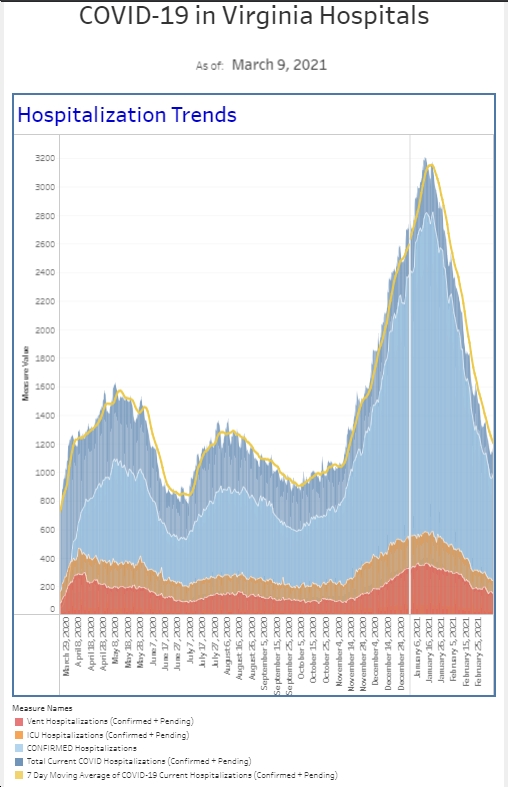

The Delta surge of late 2021 was the worst of it. The Omicron surge in January 2022 had a much higher peak – so bad here in Virginia even Governor Sweatervest himself approved of running commercials during the NFL Playoffs begging people not to go to the ER – but it was over in the space of a month.

The Delta surge? It just wouldn’t end. It was relentless. Day after day, week after week, of things getting worse and worse.

This week marked the one-year anniversary of twelve weeks of hell that left me shattered. That almost got me to give up nursing altogether. That, even looking back now, leaves me completely perplexed on how I made it through.

Given the auspicious anniversary, I thought I would try and reflect on it. Partly to help chronicle things we were going through I had no emotional bandwidth to recount at the time. Partly to try and heal from the things I saw and went though over those twelve weeks that would never end.

But it wasn’t to be. The Delta subvariant, first identified as a “variant of concern” by the CDC on June 15th, 2021, quickly took hold in the US. As the data came in on how infectious the Delta strain was, how much more aggressive it was than the previous strains, and as we watched vaccination rates struggle to climb, an atmosphere of bleak realization dawned on those of us in emergency services that regardless of how bad we’d thought things had been during the pandemic wall in December and January… this was probably going to be worse. And we were in for a bad, bad time.

By mid-July, the surge was here. Everything old was new again. But even amongst a group of people as relentlessly cynical and pessimistic as ER Nurses (more specifically, the increasingly smaller and smaller pool of nurses who’d made it through the whole pandemic), we would have never considered that the surge would effectively last until December.

As August progressed and things got worse, and turned into September with no respite whatsoever, a deal was floated to critical staff in the ER, ICU and COVID units: pick up overtime shifts for six weeks in a row, and you’d get a cash bonus of $1,000. It was a hard limit, so if you missed the total overtime numbers by even 15 minutes, you got nothing.

And I had bills to pay. The transmission in my truck had shredded and rendered it inoperable. My 10th wedding anniversary was coming up in 2022, and since my wife and I had spent the last few Augusts in the ER together – twice for COVID and once for Nazis – I wanted to go all out, take her on a vacation she’d been dreaming about since before she met me, something she absolutely deserved. And I knew my colleagues, and my community, were both hanging by a thread.

“I can make it through six weeks,” I remember thinking. “I’ve made it this far. I can make it through anything.”

Famous last words.

—

My memories of that time are a jumble of images and retained feelings from things we went through or saw.

When we would get a critically ill patient, we played the transfer game; calling every hospital in the state to ask if they had any availability in their ICU, because we had none. But, of course, none of them did either. I was on a first-name basis with some of the transfer center folks. “Hey, Susan, it’s Kellen in Charlottesville. How are y’all doing today? Oh, man, I hear that. Well, yeah, you know, I’m just doing things by the numbers, I gotta call and ask if you have any beds there in Fairfax. Yeah, I didn’t figure, but you know how it is. Okay. Well, stay safe, give the kids a hug for me.”

We would beg, borrow, cajole, and steal to hold things together. We were constantly holding things together with duct tape and twine, swapping nurses around, making deals to cover staffing holes, and floating people to different units. Every crisis we addressed would beget another one right behind it. Every sacrifice we made came with a price we knew would come due eventually. We would burn bridges, bridges that had been built carefully over years and decades, just to hold things together, knowing it would take just as long to rebuild them (if we ever could).

While this was going on, we were faced with an onslaught of hatred and misinformation. I had a patient walk out of my ER, desperately ill and in need of immediate medical intervention, because we wanted to swab them for COVID so they didn’t potentially infect the OR team, only to hear this fully cogent patient declare aloud to our entire department “Oh, you’re trying to kill me! Because COVID is a hoax; you’re one of those hospitals that is murdering patients! I’m leaving!”

I had to field phone calls from people who screamed at me for not giving their friend ivermectin. Their cousin from Chicago, who was a retired nurse, told them I needed to give their friend hydroxychloroquine immediately, and if I didn’t, I was personally responsible if they died. One person who had to wait for six hours to be seen told me that they knew we were just pretending to have long wait times to support President Biden. People who would, before I even opened my mouth to ask them why they were coming to the ER, angrily demand I not ask them to take “the jab”, because they weren’t going to take it!

I would come home at 7:30am (if I was lucky), exhausted, drawing the blackout shades in our bedroom and trying to get in a few hours of sleep before I had to pick the kids up from school. My wife, who is also an ER Nurse, worked day shift, and so while we rarely got to see one another- often going without more than a glimpse at one another for days at a time – at least someone was always there for our children.

When we did have time together, we never talked about work. Never. I knew she’d seen some very tough things. She knew I had. Discussing it was reliving it. And why anyone would want to do that is beyond me.

Well. I take that back. We did talk about it, in our own way. I remember once, after I’d had to fly a critically ill pediatric patient across the state because every single pediatric bed between here and there was beyond capacity, her sitting next to me on the couch and putting her head on my shoulder while I was watching TV on one of my precious few days off. Something she might do under any circumstances, but it was just the way she did it… letting me know I could talk about it if I wanted to.

I didn’t. But I appreciated the gesture more than she could ever know.

Six weeks. Three pay periods. As the time I’d signed up for came to a close, I hadn’t planned on signing up for another six weeks. I was burned out, and barely hanging on. Many of my friends were running for office, and I wanted to be able to finally devote some time to helping them campaign, as I knew what I was going through was hell, but nothing like what my friends in Florida and Texas were having to go through.

It was about then that a neighboring healthcare system collapsed. Well and truly collapsed. Rural Virginia was reaping the whirlwind, paying for the decisions made by politicians and corporate CEOs to allow critical community access hospitals and primary care providers in the Shenandoah valley, in Southwest and Southside Virginia, to be shuttered. This hospital turned their cardiac catheterization lab into a COVID ICU. They ordered extra morgue trailers. They went so far as to beg – beg! – people from our city, our hospital, to pick up shifts in theirs on our precious few days off, because they were desperate for any and all help. Their ICU capacity percentage went way above 100%; it went to a number that I won’t even repeat here, because it shouldn’t be mathematically or logistically possible.

Another six weeks would put me all the way to the first week of December on overtime, including a run of eleven days in a row. Eleven 7pm-7am shifts in a row.

But things were only getting worse.

So I signed up for another six-week rotation.

—

I’ve sat here watching the cursor blink at me on the Notepad screen I’m writing this piece on. Blink, blink, blink, blink. I’m trying to conjure up words that will do justice to what that last month and a half was like, but… nothing.

I remember coming home from that eleven-day stretch, to have three days off in a row, and just… laying down on the floor of my bedroom. I couldn’t sleep. I was exhausted, I was bone tired. People say “Oh, I was bone tired” as a cute aphorism until they experience what I did and go, “oh, my God, my bones actually hurt, why did I ever think I had been this tired before.” Tired as I was, though, I could not sleep. I loaded the family up in my truck and we drove down to Roanoke, Virginia, to spend a night or two at my mom’s house. The kids were excited to see Grandma, and I thought it might be nice to get away for a bit.

I couldn’t sleep. Everyone went to bed; I couldn’t sleep. At 1:30am, I laid down on the floor again and felt like I was going to die. I had chest pain, like a vise clamp was squeezing my heart. I felt it so sincerely I drove myself to the ER in Roanoke – and I don’t know how to explain fully what kind of effort it takes for an ER Nurse to drive themselves to another ER for care, but every one of my colleagues I’ve told that story to has gasped in incredulous astonishment. Everything was fine, but it was clear to me I was finally reaching the hard limit of what I could cope with.

I suddenly understood perfectly how one of my colleagues in a different state, a state whose COVID response was one of the worst in the country, had become a functional alcoholic during the pandemic. She told me she liked having shifts back-to-back, because having to work those days kept her from drinking. Having multiple days off in a row? That was where trouble was. I remember her telling me that and being sympathetic, but not getting it.

I sure as hell got it now.

During this time Terry McAuliffe lost the 2021 election, too, and several of my friends lost their races for House of Delegates. Even buried in the ER, unable to pay much attention, I’d had an inkling that things were going bad in the political arena, but I’d held out hope, I donated and voted and did everything I had the bandwidth to do. I understood perfectly well what the consequences would be if Glenn Youngkin won. I had colleagues working in states run by Ron DeSantis and Greg Abbott. But I guess that wasn’t enough for some people; I had a Democratic Party official say aloud that I didn’t deserve to run for the House of Delegates this year, because I “never showed up for Terry,” and when pointed out that was because I was in the ER, shrugged and said, “Well, that was your choice.”

I’m not even angry about that. I’m really not. It’s like being angry at your toddler for saying they hate you. They just don’t have any concept of what we went through to hold things together. And knowing what we went through… it’s just… not an understanding I would wish on anyone.

—

I made it to the first week of December. I honestly still don’t know how. I wondered if I would laugh or cry or celebrate that run being over, but it ended pretty anticlimactically. I just punched out at 7:15am from that last shift, went home, and… that was it.

It was over.

I’ve resisted telling this story. When I write things like this, I get lots of well-meaning comments. Praise. “Oh, Kellen, you’re a hero. Oh, you’re so strong for writing this.” So forth and so on.

I don’t deserve the praise. I’m not a hero. All I did was survive. I just hung on by my fingernails and survived, survived something I got to see firsthand that so many people didn’t. There’s nothing heroic about surviving. It’s more about chance and luck than anything else. I lost count of how many times that Lady Fate was the only thing that held us together.

I did my job. I did what I could to protect my colleagues and my community, but it wasn’t enough. And I get that wasn’t our fault; we were doing the best we could with what we had. We were given an impossible task to tackle with finite resources, we were fought every step of the way, and we still gave it everything we had… we absolutely did. We never held anything back, so I don’t lose any sleep over that. But that’s it- well, it’s certainly all I did. And it’s not survivor’s guilt saying that, or any other similar kind of bullshit. It’s just the truth.

But that truth is why I’m writing this piece now. That truth is why I’m running for office now.

This shouldn’t have to be made clear, but I guess I need to say it aloud: luck eventually runs out. We cannot keep our people, our communities, safe on luck alone. That’s not a strategy; it’s a suicide pact. And yet, I see everyone from the Republican incumbent I’m running against, to his colleagues in Richmond, to politicians like him across the country simply shrug, and go, “Well, things never looked that bad to me. Y’all are fine! If anything goes wrong again, I’m sure you’ll hold things together for us!”

As if we didn’t lose millions of lives, and millions more to disability. As if I hadn’t personally seen dozens of my colleagues leave the medical field forever, taking hundreds of years of experience with them. As if I hadn’t watched as we destroyed all of the professional infrastructure we’d built up over decades to try and hold things together. As if I hadn’t seen my colleagues screamed at and abused thanks to a billion-dollar campaign to demonize them.

Those of us who are “essential workers”, who are part of working families, who are on a fixed income, who don’t have a trust fund, who rely on the social safety net to keep them from hitting rock bottom- we can’t rely on fate alone to get us by. We need more than that.

And that’s what I’m going to Richmond to fix. That’s what I’m going to Richmond to fight for unapologetically. The radical, crazy idea that no Virginian should ever have to rely on luck to count on what they need to survive.

We have so many challenges coming in the near future- coming and already here! Climate change, healthcare, assaults on fundamental rights and bodily autonomy, gun violence, threats to our democracy, housing, criminal justice reform; all of these issues have problems that need to be addressed now. Not later; now.

If we want to provide for the safety, security, and stability of our people, we have to have someone unafraid to fight the people who are trying to keep that from happening.

And that’s damn well what I am going to do in Richmond.