by Josh Stanfield

On Monday, March 18 at noon, candidates will begin submitting petition signatures from registered voters in their districts (for the U.S. House, the minimum is 1,000 signatures, for the U.S. Senate 10,000) in order to get on the 2024 primary ballots. The order of candidates’ names on the primary ballot is determined by the order in which candidates file these signatures and other paperwork, and if multiple candidates successfully file simultaneously, ballot order between those candidates is determined by lot.

For the vast majority of races – those with fewer than four candidates on the ballot – ballot order is more symbolic of a strong campaign than means to gain any statistical advantage. But sometimes the fight over ballot order gets messy, like in the 2018 Democratic primary in VA-06. And sometimes, like this year in VA-07 and VA-10, there are enough candidates in the races to make ballot order potentially matter.

This year, we may see a twist in conventional wisdom about petition signatures, a twist due to a counterintuitive interpretation of what a Virginia Department of Elections official called a “really dumb law.”

James City County & Over $3,800 in Ballot Reprints

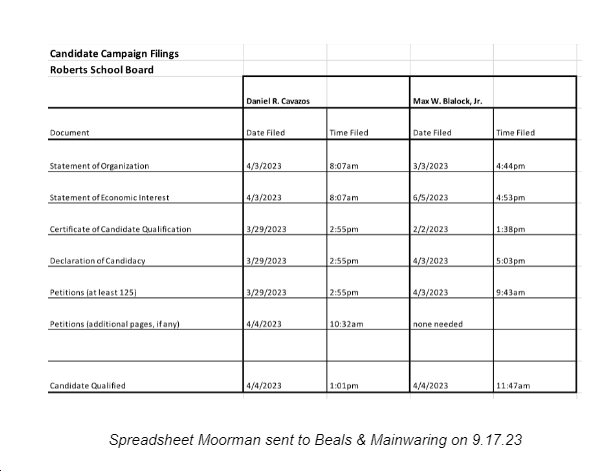

Flashback to March/April of last year: Rev. Max Blalock and Daniel Cavazos were filing the 125 required petition signatures to get on the ballot for James City County School Board (Roberts District). Though these School Board races are formally nonpartisan, Blalock was backed by the local Democrats and Cavazos by the local GOP.

According to records obtained via FOIA, on March 29, Cavazos submitted 125 signatures – but 5 were considered invalid. On April 3, Blalock submitted 125 valid signatures, and under conventional wisdom, would’ve secured first position on the ballot.

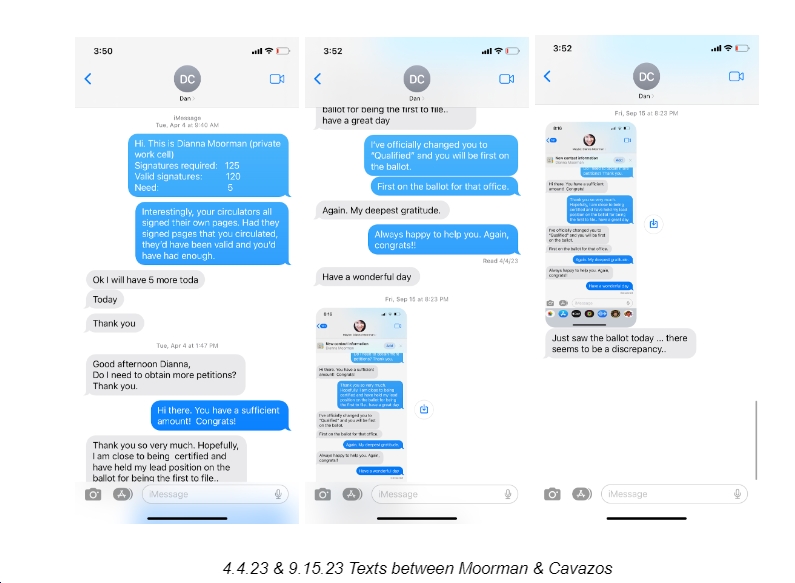

Those same records show that on April 4, James City County General Registrar Dianna Moorman texted Cavazos and indicated that he needed 5 more signatures. Within an hour of that text, Cavazos submitted the necessary additional signatures, and Moorman texted him later that day that “you will be first on the ballot.”

It turns out, however, that the ballot design reflected the conventional wisdom of petition submissions, and Max Blalock was listed first on the ballot – despite what Moorman texted to Cavazos.

Until months later, on September 15 – as ballot printing was underway – Cavazos texted Moorman: “Just saw the ballot today…there seems to be a discrepancy.” On September 16, Moorman received an email from Chris Marston of Election CFO, a compliance firm that does substantial business with GOP campaigns, mentioning Moorman’s texts with Cavazos about ballot order and containing a FOIA request.

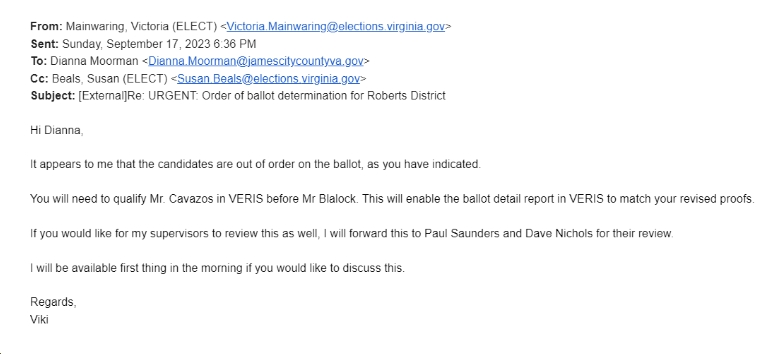

On September 17, Moorman emailed Virginia Department of Elections Commissioner Susan Beals and ELECT Elections & Registration Specialist Victoria Mainwaring, attaching a spreadsheet and requesting guidance from ELECT concerning who should be first on the ballot. Moorman also advised the James City County Electoral Board members on the 17th that “I have submitted the filing facts with ELECT and am awaiting their response. I have made a contingency plan for ballots to be reprinted and for L&A to be held Thursday at 9am.”

That same day, ELECT Elections & Registration Specialist Victoria Mainwaring replied to Moorman, confirming that the ballot order needed to be reversed and flagging her supervisors.

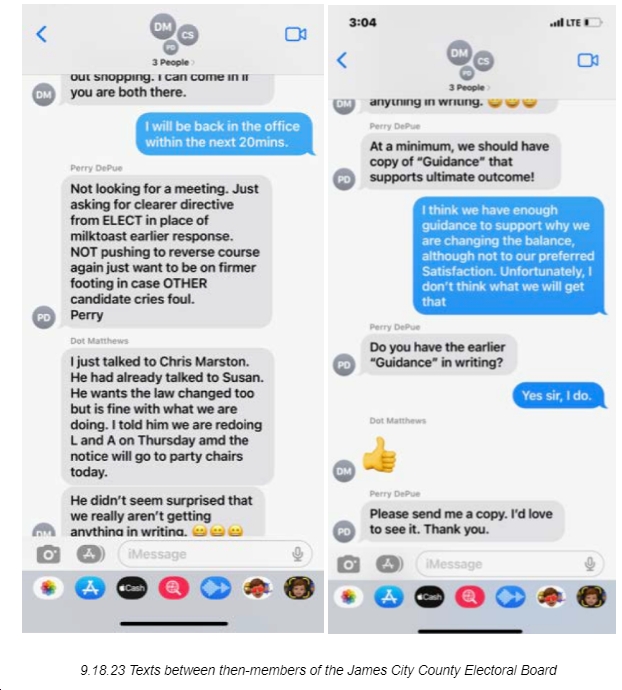

On Monday, September 18, Mainwaring confirmed to Moorman that the ballot order had been changed in VERIS, and Moorman forwarded the email to the members of the James City County Electoral Board. Text messages between Board members confirm they wanted more clarity in writing about the change:

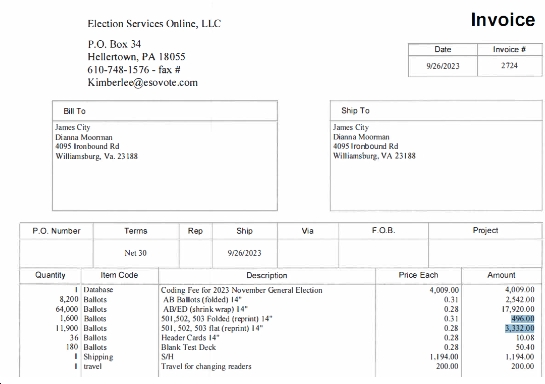

Ultimately, the ballots in this school board district were reprinted… at a cost of $3,828, according to the invoice:

The “Really Dumb Law”

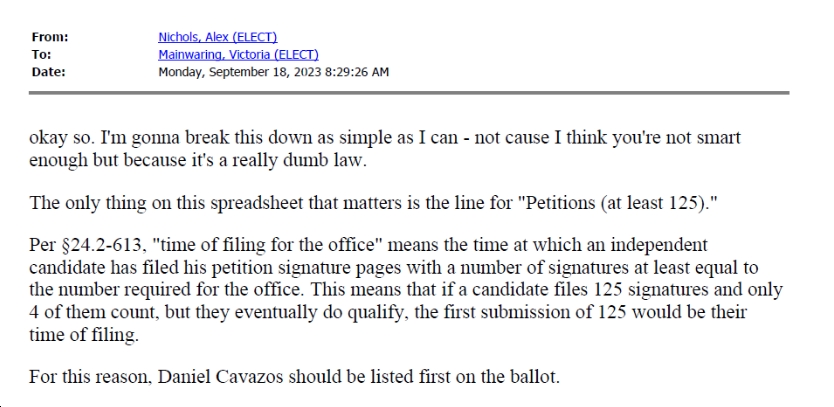

Although the James City County Registrar and Electoral Board followed the Virginia Department of Elections’ guidance in printing new ballots, they never did get a formal explanation why. Internal ELECT records obtained through FOIA show Alex Nichols tried to explain the legal situation (though he’s not a lawyer) to Victoria Mainwaring on September 18:

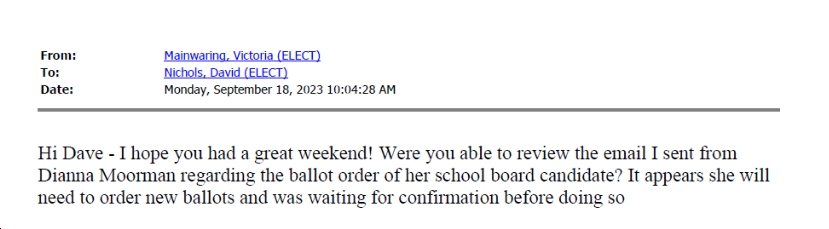

A little over an hour later, Victoria Mainwaring asked David Nichols for a review of the situation:

ELECT did not release any response from David Nichols, and no communications with the Office of the Attorney General or other legal counsel were released or withheld.

The “really dumb law” on which Alex Nichols’ legal interpretation was based reads in part:

Va. Code § 24.2-613(C): “Where there is more than one independent candidate for an office, their names shall appear on the ballot in an order determined by the priority of time of filing for the office. In the event two or more candidates file simultaneously, the order of filing shall then be determined by lot by the electoral board as in the case of a tie vote for the office.

For the purposes of this subsection, “time of filing for the office” means the time at which an independent candidate has filed his petition signature pages with a number of signatures at least equal to the number required for the office pursuant to § 24.2-506. In the case of an office for which no petition is required, “time of filing for the office” means the time at which the candidate has filed his completed statement of qualification pursuant to § 24.2-501.”

The Nichols’ interpretation suggests that since the law defines “time for filing for office” in a way that only requires filing at least the number of signatures required for the office, not the number of valid signatures, you can still secure first position on a ballot by filing an insufficient number of valid signatures – as long as you cure the problem later.

This counterintuitive interpretation could affect the 2024 primary ballots. Va. Code § 24.2-529 governing primary ballots states, in part:

“The names of the candidates for various offices shall appear on the ballot in an order determined by the priority of the time of filing for the office. In the event two or more candidates file simultaneously, the order of filing shall then be determined by lot by the electoral board or the State Board as in the case of a tie vote for the office. No write-in shall be permitted on ballots in primary elections.”

Here we lack the explicit definition of “time of filing for the office” found in § 24.2-613(C), the definition Nichols cited in his interpretation, but there’s no reason to think ELECT’s position would necessarily be different as it pertains to primaries. Party committee chairs now have two interpretations to choose from with some justification: the conventional interpretation or the Nichols interpretation.

It remains to be seen if this “really dumb law” enters the conversation this year – particularly in crowded primaries. Regardless, we now know a little more about ELECT’s idiosyncratic interpretation of that law, and some candidates might decide to turn in all their petition signatures – valid and invalid – on day one.

Lawmakers may even find it prudent to slip a “valid” into the Virginia Code, eliminating the Nichols interpretation in its entirety.

Sign up for the Blue Virginia weekly newsletter

Sign up for the Blue Virginia weekly newsletter

![Thursday News: Putin Launches Vicious Attack as Trump “Plan[s] to Sell Out Ukraine to Russia”; “Fears grow that Signal leaks make Pete Hegseth top espionage target”; “West Wing Screaming Match”; Trump’s Approval Rating Falls; “A dozen states [but not Va.] sue to stop Trump’s tariffs”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/montage0424-238x178.jpg)