While the news that geologists in Virginia and West Virginia have come out in support of uranium mining in Pittsylvania County is certainly not surprising (geologists usually work for resource extraction corporations), another controversy over energy-related extraction in the Commonwealth has recently arisen. The U.S. Forest Service has proposed a 15-year ban in the George Washington National Forest on hydraulic “fracking” to recover natural gas. That ban is being fought by industry and Republicans in the House of Representatives, including Bob Goodlatte (R-6th).

While the news that geologists in Virginia and West Virginia have come out in support of uranium mining in Pittsylvania County is certainly not surprising (geologists usually work for resource extraction corporations), another controversy over energy-related extraction in the Commonwealth has recently arisen. The U.S. Forest Service has proposed a 15-year ban in the George Washington National Forest on hydraulic “fracking” to recover natural gas. That ban is being fought by industry and Republicans in the House of Representatives, including Bob Goodlatte (R-6th).

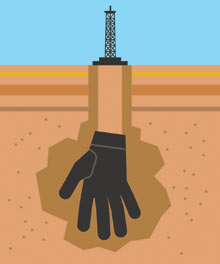

“Fracking” involves the high pressure injection (sort of like a mini-earthquake) of water and toxic chemicals deep into the underground Marcellus shale formation which extends throughout the Appalachian region and using horizontal drilling for the subsequent recovery of natural gas. Serious environmental concerns come from the large amount of water used in the process and in how to keep a toxic cocktail of drilling chemicals isolated from the environment.

At stake is the rich ecosystem of the George Washington National Forest and the water supply for many communities in the northern Shenandoah Valley, not to mention habitat for a diverse population of wildlife. In Pennsylvania and West Virginia stream contamination and land contamination by chemicals involved in the fracking process have been huge problems. A case in point is the town of Dimock in northeastern Pennsylvania. There, the town’s aquifer has been polluted so badly that water must be trucked in for residents. Diesel fuel and fracking chemical spills have occurred and the homes of resident have become impossible to sell, according to Christopher Bateman in Vanity Fair.

Burning natural gas may be less polluting that some other forms of carbon-based energy, but extraction of natural gas by fracking certainly is not without heavy costs. Fracking is an energy- and resource-intensive process. Every shale-gas well that is fracked requires between three and eight million gallons of water, according to Bateman. Volatile organic compounds from the process are burned off directly at the site, but the wastewater and the chemicals it contains must be trucked off-site for disposal. No one knows what happens to the chemicals left in the ground.

Yes, we need to find new sources of energy here at home, but at what cost? Environmental regulation of fracking has been hit-or-miss up to now, primarily because it has been left up to the states. Before fracking takes place in the George Washington National Forest, we had better look long and hard at how to protect the heritage we have been given. Otherwise, that giant uranium pit planned for Pittsylvania County won’t be the only mess we leave as our “legacy” to our grandchildren.

![[UPDATED with Official Announcement] Audio: VA Del. Dan Helmer Says He’s Running for Congress in the Newly Drawn VA07, Has “the endorsement of 40 [House of Delegates] colleagues”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/helmermontage.jpg)