Some commentators have reminded us lately of what originally inspired the nations of Western Europe to move toward unification. The impetus came after two horrific wars, originating in Europe, within the space of thirty years.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, after tens of millions had been killed and with much of Europe in ruins, some visionary European leaders understood the necessity of weaving the nations of Europe into a more whole order enabling its nations able to live together in peace, and to work together for their common good.

It is this project of creating such a more whole order — among nations that for centuries had been struggling against each other for power – to which last week’s “Brexit” vote has dealt a serious blow.

That much is widely recognized.

What is less well recognized is why all humankind has a big stake in the success of that project.

It was possible for the nations of Europe to act on the need for a more ordered system after those two terrible world wars. But waiting for after another catastrophic war to demonstrate – on the global scale — the necessity of a better order that can keep the peace among the world’s nations may well not work. Not in the world we have now, containing as it does a handful of major nuclear-armed powers among whom there is always the possibility for major-power confrontation to escalate into nuclear war.

Whereas, enough of European civilization survived WW II to rebuild and reorder their part of the world (with American help), it cannot be assumed that enough would remain in the aftermath of an all-out nuclear war to enable humankind to start constructing a more whole global order.

It is not prudent for us to depend on the experience of trauma to motivate us to move toward a desired order for human civilization as a whole. We need to be inspired to create an order that can prevent a catastrophe by the mere knowledge of that such a catastrophe is possible.

And how can we deny that such a possibility is very real, and perhaps – unless we work toward the necessary destination, even likely?

We already had one crisis, during the cold war, that came alarmingly close to being such a planetary cataclysm: the Cuban Missile Crisis. We were fortunate, in that crisis, that the two nuclear superpowers succeeded in navigating to a peaceful resolution. But it could have gone otherwise.

Should we not imagine that, in the next century or two, other crises of such gravity would arise? And is it not only reasonable to imagine that, in such a sequence of eyeball-to-eyeball confrontations, at some point our luck would run out?

What is the life-expectancy of someone who plays Russian roulette on a regular basis?

Even in today’s world, events spinning out of control into nuclear war cannot be ruled out. At this moment, two areas of military tensions between major nuclear powers roil the international scene: 1) in the region of the Ukraine, between Putin’s Russia and the United States (and the West), where the Russians have already seized Crimea by force and 2) in the South China Sea, between the United States and China, over the Chinese assertion of sovereignty over the South China Sea where other, smaller nations also have legitimate claims.

And when one adds to that the possibility that soon the president and commander-in-chief empowered to deal with such tensions might be Donald Trump, the reality that there is no guarantee our civilization can survive its current disordered state indefinitely becomes still clearer.

(The possibility of war is not the only powerful and urgent reason it is necessary to create a more whole global order. Another is revealed by the growing crisis over climate change. In a better ordered civilization, perhaps the world would have been able to respond a quarter century ago – at the time of the international conference in Rio over climate change – instead of continuing to lose precious ground while various major sovereign powers — and major consumers of fossil fuels — dithered. In the larger picture, the long-term viability of human civilization depends upon humankind’s ordering its activities to live in harmony with the only planet we’ve got.)

What this means is that if future generations are to have a decent future – or perhaps any future at all – human civilization as a whole will have to meet something of the same challenge as Europe first began to meet nearly 70 years ago.

We should see Europe, then, as having been at the vanguard of one of humankind’s most essential tasks. The whole human species — the descendants of all of us – have an immense stake in whether the Europeans succeed in showing how nations can move toward that better-ordered world our descendants likely need for us to create.

To the extent that the Europeans fail, humankind as a whole will have to find some better way to blaze the trail; to the extent they succeed, they provide a map that might guide our progress to meet the challenges on the larger scale.

In many ways, the European effort has been an enormous success. In any ranking of “the most decent societies” since civilization first arose millennia ago, the nations of Western Europe, over these past two or three generations, would rank at the very top. In the nations that have been engaged in the unification of Europe, hundreds of millions of people have able to live lives in peace and prosperity and freedom.

But the British vote to leave the EU (which is the present culmination of generations of European effort to create that better order) — combined with strong similar anti-EU sentiment in several other member nations on the continent – give a clear indication that Europe’s efforts have also gone awry.

Could so much negative feeling toward the EU exist if all were being done right?

The key question of the moment is, therefore: Will the powers in the EU work honestly to identify and correct the missteps they have made?

In a column published in The New York Times the week before the Brexit vote, Paul Krugman declared that, if he were British, he would vote Remain, but with mixed feelings because of his “full awareness that the E.U. is deeply dysfunctional and shows few signs of reforming.” “The most frustrating thing about the E.U.,” Krugman says, is that “nobody ever seems to acknowledge or learn from mistakes.”

And perhaps that’s a good place for the EU to start. And, though there are other problematic aspects of the EU to examine, perhaps the inquiry into this “most frustrating thing” could begin with the example of the counter-productive policy of “austerity.”

Two questions about the EU’s austerity policy need answers: 1) How did an idea like austerity – the idea of imposing contractionary policies at a time of severe economic downturn, an idea that doesn’t pass the Econ 101 test – ever get adopted (both by the EU in the euro area and by the Cameron government in the UK)? And 2) Why is it that the EU held unwaveringly to that disastrous policy, even as the evidence of its wrong-headedness piled up, and as Krugman and other excellent economists made crystal clear the case against it?

(People point rightly to the issue of immigration in the Brexit vote, but history teaches us that it is at times of economic pain that people are most prone to xenophobia, and the misguided austerity policies inflicted plenty enough economic pain on the less privileged in the UK to account for Brexit’s 4% margin of victory.)

Building a whole order of civilized societies is a challenge that will take every bit of creativity and intelligence and wisdom that people can muster. How do we create a system that is ordered enough to prevent war, give people a sufficient say in charting their destiny, provide a comfortable life for people, protect the integrity of the biosphere, and give peoples the latitude to express their unique cultural/national identities?

Charting a path to such a destination is a challenge so daunting that the ability to spot wrong choices early and make mid-course corrections will be essential.

The Brexit vote has brought the Europe-scaled version of this civilization-wide challenge to such a fork in the road. From the present juncture, the EU can continue to break down because of its errors and its inability to learn and change. Or, it can revive itself by showing a readiness to reform that, as Krugman says, has so far not been visible.

It would be welcome news for all of us on this planet if the powers of the EU were to say, soon, before other nations (like the French or Dutch) might hold referenda of their own: “We understand that mistakes need correcting and improvements must be made. We are determined to identify and make those changes as quickly and wisely as we can.”

The books by Andrew Bard Schmookler include The Parable of the Tribes: The Problem of Power in Social Evolution.

.

![VA DEQ: “pollution from data centers currently makes up a very small but growing percentage of the [NoVA] region’s most harmful air emissions, including CO, NOx and PM2.5”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/noxdatacenters.jpg)

![Thursday News: “Europe draws red line on Greenland after a year of trying to pacify Trump”; “ICE Agent Kills Woman, DHS Tells Obvious, Insane Lies About It”; “Trump’s DOJ sued Virginia. Our attorney general surrendered”; “Political domino effect hits Alexandria as Sen. Ebbin [to resign] to join Spanberger administration”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/montage010826.jpg)

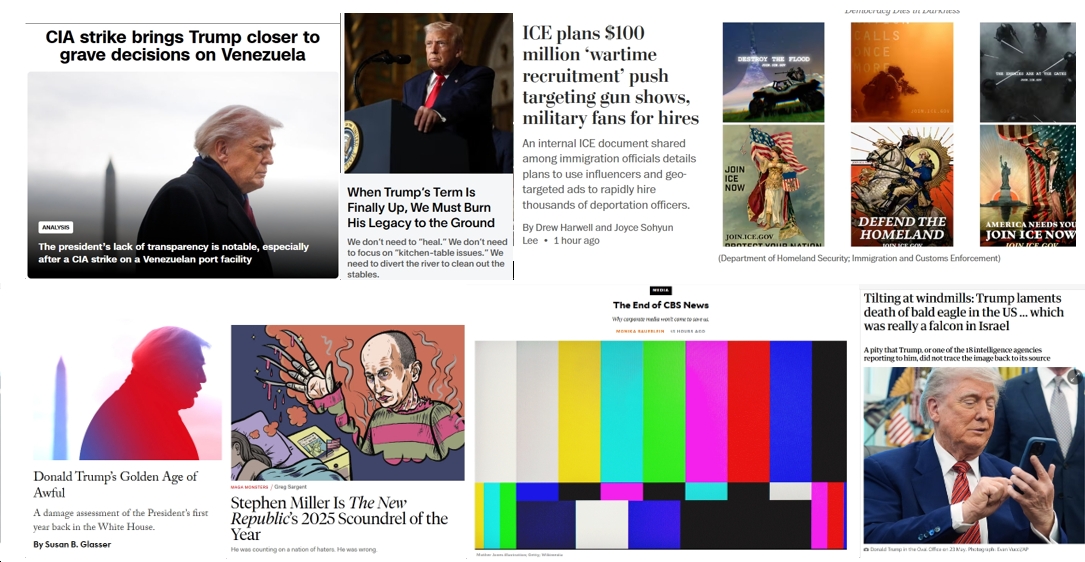

![Sunday News: “Trump Is Briefed on Options for Striking Iran as Protests Continue”; “Trump and Vance Are Fanning the Flames. Again”; “Shooting death of [Renee Good] matters to all of us”; “Fascism or freedom? The choice is yours”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/montage011126.jpg)