By David T.S. Jonas, former economic policy aide to Senator Al Franken (D-MN) and served as policy director to Governor Terry McAuliffe’s Commission on Integrity and Public Confidence in State Government.

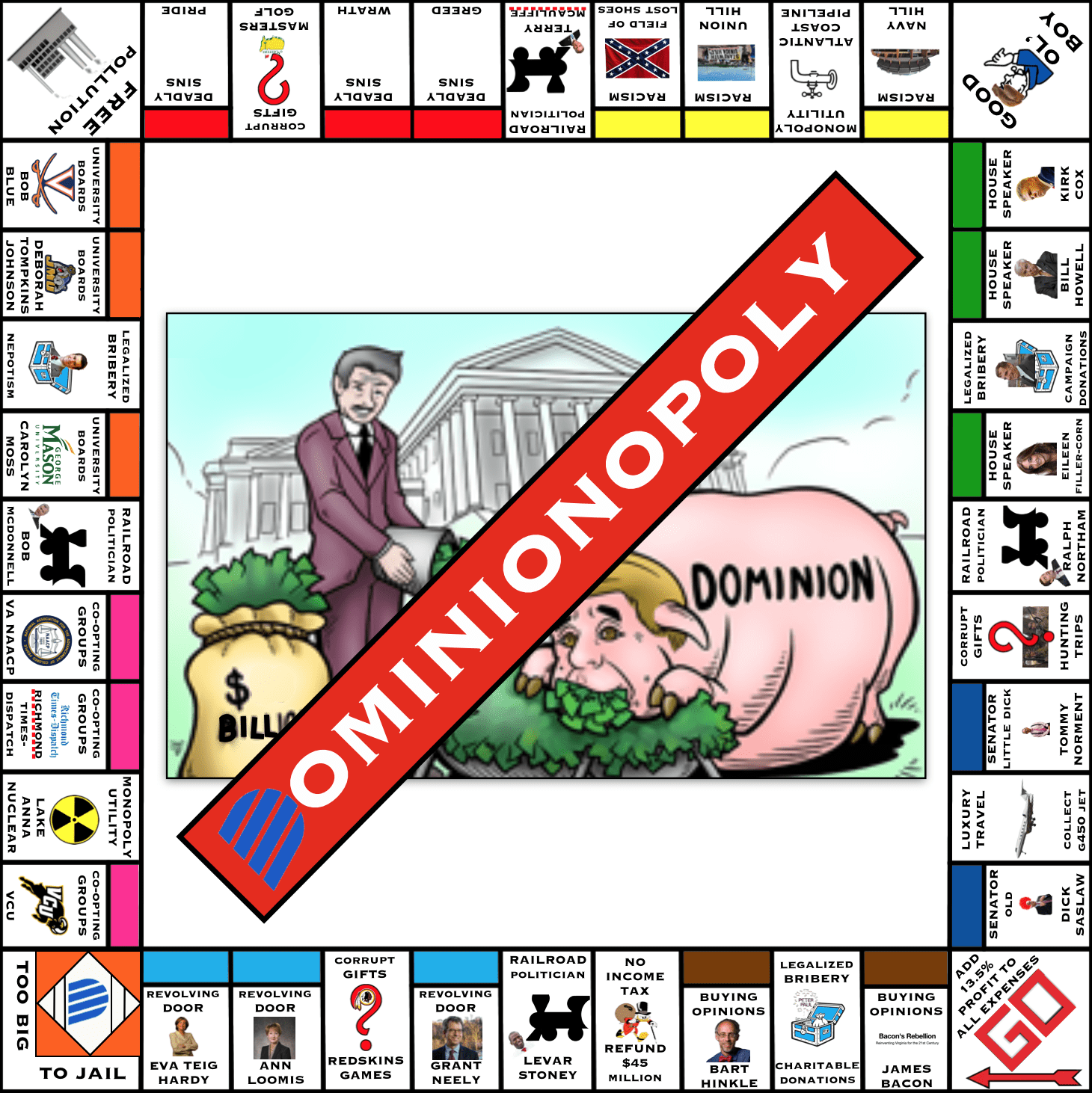

Back when I served as the policy director for Governor Terry McAuliffe’s Integrity Commission—which recommended reforms to Virginia’s ethics laws in the wake of allegations against previous Governor Bob McDonnell—not a day would pass without a commission member or a public official expressing concerns that comprehensive ethics reform would penalize “routine politics” and dissuade good people from seeking higher office.

When I heard these concerns, I used one tried-and-true line to get through to them what was in it for the public officials themselves.

“You’re not doing this because politicians are inherently unethical people. You’re doing this because there’s always going to be a federal prosecutor who wants to make a name for him or herself bagging a Virginia politician.”

I was hoping that this bit of rhetoric would help legislators understand that the laxer Virginia’s ethics laws were, the more likely that federal prosecutors would try to catch a Virginia public official operating in the grey area between Virginia and federal law. This is precisely how Governor McDonnell got into so much trouble: he may have been operating within the bounds of Virginia’s rules, but he was on much shakier ground within federal law.

I believed then—just as I believe now—that strong ethics laws best protect Virginia’s public officials from overzealous federal prosecution. By establishing clear rules that prevent against even the appearance of a conflict of interest, public officials won’t ever approach even the bare minimum of what might constitute corruption under federal law.

Sadly, the Supreme Court took the opposite approach in its recent McDonnell decision. The Court essentially narrowed the definition of what constitutes an “official act,” giving public officials greater leeway in freely exchanging access for gifts and campaign contributions. Many political commentators—including those at the Washington Post—have suggested that this decision will make it harder to prosecute public corruption. Perhaps, but my research suggests that prosecutors will be even more eager in pursuing public corruption cases, and that juries will be just as eager to convict.

To understand why the Supreme Court—in all likelihood—has increased the chances of more public corruption cases, consider the behavioral incentives at play. For the public official who is happy to trade influence for money (insofar as they believe it legal), the McDonnell decision will only make them more likely to assume their own self-assessments of their favor-dealing are legally sound. These officials will quite rationally push the boundaries of common decency even further than before. Prosecutors—knowing that even more corrupt behavior is occurring—will devote extra resources to investigate and see whether they can bring cases against these officials. And jurors—who will witness these heightened “routine” forms of corruption—will vote to convict, because all of this registers in their hearts and minds as tantamount to quid-pro-quo corruption, more nuanced jury instructions notwithstanding.

This is the fundamental mistake the Supreme Court made in its McDonnell decision. The Court’s legal analysis may be on solid ground, but its tangible effects in the real world will never approach the hypothetical world they have constructed in their decision. Just as they have with campaign finance in Citizens United, the Supreme Court has put into place a kind of doomsday machine, where each player’s self-interest leads to ever-more public corruption prosecutions. And when juries reach verdicts that contradict the McDonnell decision, the courts will have to intervene again to narrow the scope of what constitutes corruption, beginning the cycle anew.

Obviously, these kinds of prosecutions are relatively rare, so we’re hopefully only talking about a handful of prosecutions a year. But again, it’s the behavioral effects of the McDonnell decision that the public ultimately cares about. And for Virginia in particular, the flaws of the McDonnell decision will manifest themselves rather quickly and starkly. Legislators in Virginia who would be well served by a stronger ethics regime will now be able to cite the Supreme Court to not only halt additional ethics reforms, but to roll back the ones made in 2014 and 2015 in the aftermath of the McDonnell revelations. Leaders in both parties have already suggested that concerns about ethics are a media creation, or even worse, that “you can’t legislate ethics.” The McDonnell decision gives these leaders the cover needed to keep such a fiction going.

Until officials and judges come to appreciate the massive gulf between public perception of corruption and their own self-evaluations of it, more prosecutions, more convictions, more ruined careers, and more thrown out verdicts will be coming Virginia’s way.