I’ve been trying to figure out why Tom Perriello, who public polls showed neck-and-neck with (or even ahead of) Ralph Northam, lost the Virginia Democratic gubernatorial primary by a substantial, 56%-44% margin on June 13. Here are my top dozen reasons; please feel free to add your own in the comments section.

1. Nearly unanimous endorsements from Virginia Democratic heavy hitters (Gov. Terry McAuliffe, Senators Mark Warner and Tim Kaine, AG Mark Herring, pretty much every other Democrat holding elective office in Virginia). I agree with these comments in the Washington Post’s analysis of Perriello’s defeat:

…the results had more to do with timing and the strength of the state’s party apparatus than with ideology, analysts say.

Lt. Gov. Ralph Northam, who beat Perriello for the Democratic nomination by 12 percentage points, had the backing of nearly every Virginia Democrat elected to state and federal office — the result of years of cultivating relationships.

How many votes did all those endorsements gain Northam? I’d argue a lot, given the fact that Kaine, Warner, McAuliffe, Bobby Scott, Donald McEachin et al actually got out there and campaigned hard for Northam, sent out emails, etc. I find it almost impossible to believe that these endorsements didn’t have a big impact, particularly on older voters – who almost certainly made up a huge segment of the Democratic primary electorate, and who like/respect/voted for Kaine, Warner, McAuliffe, Scott, McEachin, etc.

2. Getting massively outspent: Again, from the Washington Post’s analysis of Perriello’s defeat:

And [Northam] outspent Perriello by $1.4 million on advertising, affording himself a heavy television presence — especially in the costly metropolitan Washington market — in the last weeks before the election.

“The lesson here was you cannot get in a race very late and underfunded against a candidate who has been raising money and organizing for a long time and who has every meaningful endorsement from the Democratic Party,” said Jennifer Duffy, who monitors gubernatorial contests for the nonpartisan Cook Political Report. “I don’t think this has anything to do with progressivism.”

Now, I’m not saying you can’t win if you get outspent. In 2006, Jim Webb was outspent by perhaps 5:1 by Harris Miller, yet Webb won. But if you’re going to be outspent that heavily, you’d better offset it with other stuff, like Webb’s large (1,000 or so by June 13) “ragtag army” of grassroots and netroots supporters. No question, Perriello had passionate grassroots and netroots supporters, but whereas in 2006, the grassroots ratio was overwhelmingly in favor of Webb, in 2017, I’d say it was much more even, or possibly even advantage: Northam. That’s not going to cut it, especially when you’re getting outspent as “bigly” as Perriello was…

3. Getting in wayyyy too late. Not that there was much if anything Perriello could have done about this, as almost nobody saw Clinton losing to Trump, and also given that Perriello was busy with a very important diplomatic assignment from President Obama (plus Perriello was “Hatched”). Still, it was a huge, ultimately insurmountable problem to have gotten in so late, after Northam had basically locked up almost every Virginia endorsement, big Virginia donors, etc. Also, getting in the race so late meant that Perriello had to race to build an effective campaign, raise money, introduce himself to Democratic voters (most of whom only vaguely knew who he was, since he only served one term in Congress, from the 5th district, back in 2009-2010), etc, etc. In short, Perriello set himself an almost – or actually – impossible task, and in a way the fact that he ended up with even 44% of the vote shows you the potency of his message – and of the messenger. In the end, if Perriello had gotten in 6 months, a year earlier, who knows…but he didn’t, and the rest is history.

4. Democratic voters overwhelmingly pleased with Gov. McAuliffe (so why not go with his Lt. Governor to succeed him?). For instance, a Quinnipiac Poll in February 2017 found that McAuliffe’s approval rating among Democrats was 82%-6% (+76 points). As for Northam, most Democratic voters didn’t really know him, but of those who did, his approval was 34%-2% (+32 points). And while Perriello’s approval (39%-4%) was also very high among Democrats who knew enough about him to express an opinion, in the end Northam was running as the de facto incumbent, which meant that Perriello needed to make a strong argument not just for “why Perriello” but also for “why NOT Northam?” Implicitly, that also implied that Perriello needed to make some sort of case against Terry McAuliffe, but other than on Dominion and its proposed pipelines, I saw no evidence of that (nor am I at all convinced it wouldn’t have backfired badly).

5. Perriello pledged to run a “positive campaign,” and he overwhelmingly stuck to that pledge. The problem, again, is that Perriello needed to make the argument not just “why him” but also “why NOT Northam?” And staying positive made that difficult. Meanwhile, while Northam himself overwhelmingly stayed positive, some of his surrogates (e.g., Dick Saslaw, NARAL Virginia) hit Perriello hard, and Perriello never seemed able to completely put to rest his former “A” rating from the NRA or his Stupak vote. Compare that to the Virginia GOP gubernatorial primary, where Corey Stewart pounded the crap out of Ed Gillespie, while Gillespie mostly stayed above the fray (or out of it completely), and where Stewart almost beat Gillespie. Another example is the 2006 Virginia Democratic primary for U.S. Senate, where Harris Miller slammed Jim Webb as a racist, misogynist and anti-Semite, and where Webb and his supporters pounded Miller just as hard — as a slimeball lobbyist outsourcing American jobs, etc. So yeah, almost everybody says they hate “negativity,” but in many elections, it sure seems to work. In this election, who knows what would have happened if Perriello had hit Northam hard(er); maybe it wouldn’t have worked, or perhaps it would have even backfired on Perriello. But the bottom line is that Perriello got hit hard and mostly didn’t respond in kind. I find it hard to believe that didn’t hurt him.

6. Northam quickly and aggressively moving to keep Perriello from gaining a monopoly on anti-Trump sentiment. For VERY good reasons, Democrats despise Donald Trump, and Tom Perriello burst onto the scene in early January 2017 attempting to harness that anti-Trump energy and ride it to the Virginia Democratic gubernatorial nomination. Smart strategy, and it MIGHT have worked, except that the Northam campaign didn’t allow it to work. I was at the Mt. Vernon Democrats’ Mardi Gras party and straw poll on March 5, which was quite possibly the first time Northam unveiled his “narcissistic maniac” line in public. And it worked; the crowd ate it up, cheered it, etc. Very smart move by Northam’s campaign (note: even if shouting “narcissistic maniac” is almost the polar opposite of Northam’s “moderate,” calm brand/persona, Democratic voters didn’t seem to care…).

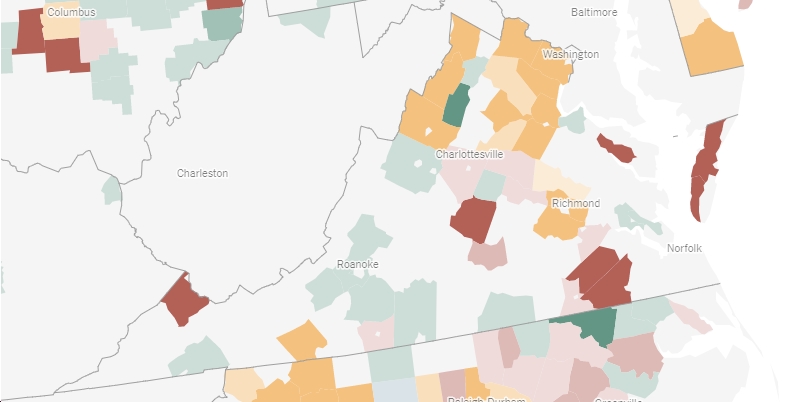

7. Northam moved to adopt many of Perriello’s progressive positions — at least rhetorically, and at least for the Democratic primary. On issue after issue, with the exception of Dominion Power and the pipelines, I’d argue that Northam was able to largely neutralize Perriello’s advantage when it came to being most progressive on the issues. Even if some of Northam’s proposals might have been somewhat less progressive than Perriello’s, they were progressive enough so that Northam could plausibly claim he was no less strong – or even stronger, in the cases of guns and women’s reproductive freedom – than Perriello on the issues that most matter to progressives. Note that on the Dominion/pipelines issue, where Northam was less able to counter Perriello, he got trounced in areas directly impacted by the proposed pipelines (e.g., Northam lost Nelson County by an eye-popping 91%-9%; lost Staunton and Bath County by 72%-28% margins, lost Augusta County 65%-35%, etc.).

8. Perriello got the higher turnout he said he needed to win, but it didn’t work. Perriello’s campaign made it clear that they were counting on much higher turnout than we saw in past Virginia Democratic primaries (e.g., 156k in 2006, 319k in 2009, 144k in 2013), and that if he got it, he’d win. Well, he got it (543k Democratic votes on June 13, 2017)…but he lost anyway. Why? There’s no public exit polling data, but it’s clear that while the electorate expanded in numbers, it didn’t necessarily change significantly in terms of composition (e.g., a lot more young voters, “presidential-only” voters, etc.) — at least not enough for Perriello to overcome Northam’s many advantages. For instance, Perriello spent a lot of time visiting college campuses, trying to get young people fired up for his candidacy, but it’s not clear that it worked to bring out legions of young people, certainly not enough to counter…

9. Northam trounced Perriello among older voters. Ben Tribbett gets a major “hat tip” for pointing this one out to me. Check out Greenspring precinct in Fairfax County, which is basically dominated by a large retirement community, and where Northam racked up an incredible margin of 465-65 (88%-12%). More evidence? Check out the results at Heritage Hunt– another large retirement community – in PW County, which went 74%-26% for Northam. Or check out The Hermitage precinct in Alexandria (another big retirement community), which went 71%-29% for Northam. We could go on all day with this, but you get the picture. The problem is that the Democratic primary electorate tends to be older, so if you are getting beaten badly among older voters, you’re almost certainly not going to win the election.

10. Perriello also spent a TON of time in “red,” rural parts of the state, and as this VPAP graphic shows, it worked to an extent, with Perriello racking up big margins in Southside, the Shenandoah Valley, Southwest Virginia and the Piedmont areas. The problem for Perriello is that margins in those areas weren’t big enough to overcome getting swamped in Hampton Roads and also losing Northern Virginia (albeit not by a huge margin). So yeah, it was the right thing to do in many ways for Perriello to spend time and resources engaging “red” parts of Virginia; the problem is that he needed more time (or to clone himself – heh) in order to ALSO court voters in places like Fairfax County (where Northam won 60%-40%), Arlington County (where Northam won 62%-38%) and Alexandria (where Northam won 61%-39%). Those three localities combined added up to nearly 140k Democratic votes cast, out of 543k total in the election, and margins upwards of 30k votes for Northam (note that Northam’s overall margin of victory was 64k votes). So…again, Perriello started too late and didn’t have the resources to compete in the expensive D.C. metro media market.

11. Adding to Perriello’s problems in the D.C. suburbs was, possibly, the Washington Post endorsement. But as I explored here, who knows if that really made a difference, as it has had a mixed track record (at best) of results in the past.

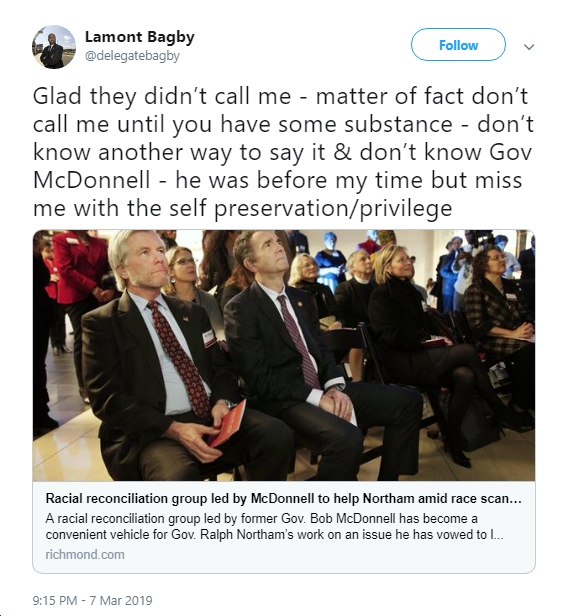

12. Northam won African-American voters. For instance, Virginia Beach went heavily (67%-33%) for Northam over Perriello in the Democratic primary; Chesapeake went 69%-31% for Northam over Perriello; Sussex County and Greensville County each went 72%-28% for Northam; Charles City County went 73%-27% for Northam; etc. You simply can’t lose African Americans by a wide margin in a Virginia Democratic primary and have much chance of winning the nomination. End of story.

So those are a dozen reasons that spring to my mind as to why Tom Perriello lost to Ralph Northam on June 13. Again, please add your own reasons in the comments section – and let me know what I missed. Thanks.