If Richmond told the truth about Dominion’s Coliseum plan, every article would begin by stating the most obvious fact: Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney wants to run for Lieutenant Governor in 2021, and Dominion is the state’s largest corporate campaign donor. But because Richmonders live in a web of propaganda and docility spun by people who want to maintain their lucrative monopoly on political power, these salient facts are rarely mentioned. The people running this scheme are con artists: this is why it is so important to tell the full truth about the lies and corruption that over the past two years have metastasized and brought normal politics to a standstill.

(Much of the following appeared as Chapter 3 of The Virginia Way: Democracy and Power after 2016.)

In Richmond’s oligopolistic media landscape, the Richmond Times-Dispatch set the agenda for other local news organizations, and what was printed there became common knowledge among residents who kept up with the daily news. On June 19, 2017, K. Burnell Evans published a horrifying exposé on a city elementary school just one and a half miles from the state capitol. She reported that “teachers begin their days by wiping rodent droppings from students’ desks, said Ingrid DeRoo, the George Mason [Elementary School] site coordinator for Communities in Schools of Richmond. ‘Some teachers wear breathing masks all day in order to teach,’ DeRoo said of the air quality in what is widely acknowledged to be the district’s worst school building among dozens in need of major repairs.” Mason had opened ninety-five years earlier and was last renovated when Jimmy Carter was president. The story fomented a passionate response across the city: parents and teachers donned surgical masks in public meetings; politicians pledged to do better; a petition to fix the problem collected 14,000 signatures in a city of 230,000; and reporters wrote dozens of follow-up pieces in the city’s other news outlets.

The Richmond School Board called a public meeting to hear citizens’ concerns. They responded with a litany of severe problems: “extreme hot and cold conditions, leaking bathrooms, falling tiles and infestations of bugs and rodents in their classrooms. A teacher said she regularly has to rescue children trapped in bathrooms, due to the failure of old doorknobs.” “My son has been sick 10 times in a row, and I can’t afford to miss work,” a parent of two children at Mason said. Fourth-grade teacher Hope Talley told the board: “Our parents want what’s best for their kids, just like any other parent. They speak [their fears] to us, we hear them, and we have to explain why their child had to do without heat today.” “From 2006 to 2017, I’ve cleaned up rat poop every morning before my kids come in,” she told a reporter. “Every. Day.” “I cannot stress to you enough that the building of George Mason is in a state of emergency,” DeRoo said. “It is unsafe, unsanitary and harmful to our students and staff.”

Interim Superintendent Tommy Kranz noted that the “building leaks like a sieve.” He acknowledged to Evans that every couple of months, the smell of natural gas became so overwhelming that “the fire department and city officials respond.” On the other hand, he maintained the school was safe and stated that “if I wouldn’t send my grandchildren into a building, I’m sure not going to send anyone else’s child.” (Two years earlier, Kranz had sung a different tune, saying that the slightly better but still inferior Overby-Sheppard Elementary School “isn’t one we should have our children in.”) He proposed options for Mason with costs ranging from $105,000 to $10 million; building a new school would cost “between $22 million and $35 million” and would take years to complete. The school board meeting adjourned without action, guaranteeing that the elementary would remain “a place where children will still confront the acrid smell of urine.”

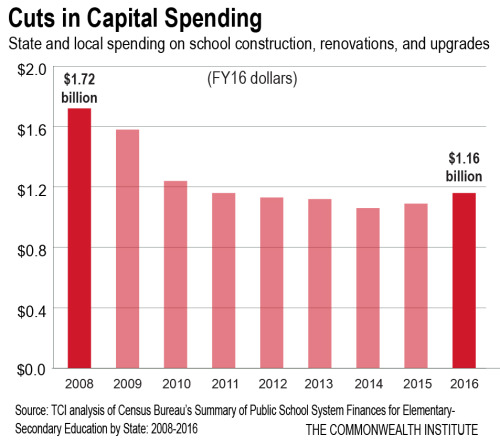

It was no surprise when the Board voted two weeks later to fund the absolute lowest option presented, for $105,000. To some extent, the Board’s hands were tied, as overall tax and budget levels were set by the Mayor and City Council. School Board Chairwoman Dawn Page noted that they had “facilities plans for all schools dating back 20 years, but with no funding, the plans cannot be executed.” In the most recent example, after the Board experienced a 100% turnover after the 2016 elections – not a single member was reelected, though two successfully ran for City Council – the new members requested $207.4 million for “school buildings needs” and received less than 4% of their request from City Council.

Many residents felt that Richmond government had plenty of money to address these issues. “We’re not lacking in money, y’all, we’re lacking in moral commitment,” said former Councilman Marty Jewell. Richmond protected its bond rating by assiduously maintaining a “self-imposed,” arbitrary debt level. Even within this constriction, the city had “about $8.5 million in [bond] capacity through 2021, and about $321 million combined between 2022 and 2026. Richmonders frequently pointed out that city government had built the Washington Redskins a $10 million training camp and paid them a $500,000 annual subsidy, based on lofty promises that never materialized, just as experts predicted they would not. The Richmond Times-Dispatch published “a photograph of a decrepit boys’ bathroom at the city’s George Mason Elementary school, last renovated 37 years ago, showing two of four urinals in working order and only one operational sink.”

The editorial board angrily wrote:

“Whatever publicity Richmond might be getting out of the [Redskins] deal can’t begin to stack up against the need to improve Richmond’s schools. Fixing them would do more for the city than any sports or entertainment offering possibly could. As any real estate agent will tell you, schools are the top concern for most people who are looking to relocate. They’re the main reason young families move out of Richmond to the counties, and a major reason families from the counties don’t move into the city. Nobody from outside the area is ever going to look at the city and say: ‘I’m going to move to Richmond. My kid will have to sweep rat droppings off his desk at school and his teachers will have to wear surgical masks because the air is so bad, but at least I won’t have to drive far to watch Kirk Cousins run drills.'”

This was just the most egregious example: the city had somehow shelled out more than $20 million—about the price of a new school—to Stone Brewery to build a restaurant and small brewery in the city. Nor was it all the fault of city council and the mayor. Jason Kamras, who came in as a new superintendent in late 2017, would make $250,000 per year, and his top five staffers would make roughly $180,000 each, about $30,000–$50,000 more than each had made the previous year in top positions in Washington, D.C.’s public schools. For comparison, the Virginia secretary of education made about $160,000, and the U.S. secretary of education made around $200,000 per year. Richmond was only the twelfth-largest school district in Virginia.

Doug Wilder had attended Mason when it was segregated. “Recently an advertisement appeared requesting volunteers to help paint George Mason Elementary School, so that it might be opened in September,” he lamented. “Imagine how that made parents and students feel about their status in the community—about their grasp of the American Dream.” Wilder and other commentators noted the remarkable disconnect between the impassioned public debate over the Parisian Confederate statues on Monument Avenue and the resistance to improving toxic city schools that were living monuments to white supremacy.

While the recriminations continued, another school year started with little to distinguish it from the prior one. A group of about a hundred people, including teenagers from Henrico High School, volunteered to apply some fresh paint to the hallways before Mason opened its doors for the fall. On the day of volunteer action, “hot water would not turn on and the bathroom door would not lock on the bathroom at the school’s main entrance.” “The rest of these fixes are nothing but expensive Band-Aids for problems that we shouldn’t be continuing to have,” said teacher Hope Talley. “I hate the expression, ‘Lipstick on a pig,’ but that’s all I can think of,” said another teacher. Three weeks after the school reopened for the fall, water there tested high for lead, and the school had to begin “providing bottled water to students, faculty and staff.”

WHY ARE RICHMOND’S SCHOOLS THE WORST IN THE STATE?

No Richmonder would claim that these problems were unique to George Mason Elementary. Something deeper was happening: Richmond was one of the wealthiest areas of the state, but its public school system had the worst high school graduation rate in Virginia. Evans’s original piece acknowledged the inertia of decades of inaction: “The issues that arise at every public meeting—from childhood trauma to challenges with special education—are so chronic and entrenched that they have become enshrined in a gallows humor–style bingo sheet passed around at Monday’s meeting. On the list are the school’s outdated facilities, which have been the subject of years of successive plans and little action.”

Heartbreaking stories about the city’s dilapidated school buildings had become their own beat among reporters, commentators, broadcasters, and anyone else who cared to notice. The tales did not become less wrenching for their frequency; so widespread and indisputable were the facts and pain caused to innocent children that each story could fairly present a new and different problem. The prior analogue to Evans’s 2017 article was a 2014 cover story in Style Weekly, Richmond’s venerable newsmagazine. The indelible images there were from Fairfield Court Elementary, where “watery, foul-smelling drops of diluted tar fell into classrooms and hallways” and “a ceiling tile fell on a student.” The superintendent said that “the buildings are the worst he’s seen in a career that includes Washington’s notorious public schools.” Two school board members (the two who would be elected to city council in 2016) looked through past reports and came to the same conclusion as Evans: “There’s the report from 2002 calling for the closures and renovations and new buildings. A 2007 report calling for the same. They outline critical building issues that remain unaddressed [sic].” George Mason Elementary School was on both the 2002 and 2007 lists of schools to replace. Other plans from 2012 and 2015 had “collected dust on office shelves.” “We’ve had plan after plan after plan to fix things,” said the school board chair, “and what has changed?”

The reason nothing changed was clear. “We have resegregated schools that are underfunded and get blamed for the deliberate segregation that has been imposed on them,” said Reverend Ben Campbell, Rhodes Scholar and author of Richmond’s Unhealed History. “The General Assembly isolated the City of Richmond and made it economically nonviable in the middle of three affluent suburban counties that were created for the purposes of racial segregation.” Many of Virginia’s “great men” had dedicated the bulk of their careers in the mid-twentieth century to supporting one of the country’s greatest crimes, racial segregation, by shuttering public schools rather than having black and white children attend school with their neighbors. This state policy violated the Brown decisions, and federal district court Judge Robert Merhidge nearly compelled Richmond to annex much of the adjoining suburban counties, as many comparable cities from Charlotte to Chattanooga to Louisville had done voluntarily. Richmond could have avoided so many of its problems if this ruling was not enjoined by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals and then upheld by a 4–4 U.S. Supreme Court decision that Justice Lewis Powell, who had served on the Richmond School Board, recused himself from. Richmond really had, in a grotesque sense, “a perfect school system,” said a local nonprofit leader, “because it was designed to give children of color an inferior education and put them in inferior buildings and teach them as little as possible, and that’s exactly what we do every day.”

History does not present controlled experiments, but it is important to consider what happened with Lost Cause iconography in Richmond and elsewhere in the South in recent years. After a Confederacy-glorifying lunatic murdered black churchgoers in 2015, South Carolina—the birthplace of the Civil War—immediately removed the Confederate flag from its capitol grounds. New Orleans—hardly a bastion of racial tolerance—similarly removed its Confederate statues from 2015 to 2017. When its ninety-foot-tall Lee monument was taken down in Lee Circle in May 2017, journalists outnumbered the protesters, there was no violence, and people returned to their daily lives. When a Lee statue faced relocation in Charlottesville in August 2017, thousands of neo-Nazis and other psychopaths—the leaders of which were UVA alumni but most of whom were not from Charlottesville—rioted in its streets and murdered a peaceful counter-protester. In 2019, the statues on Monument Avenue in Richmond—Lee, Davis, Jackson, Maury, Stuart, easily the most prominent Confederate memorials in the world—remained untouchable except by an occasional activist who may douse one with red paint. Moreover, the position of the Richmond Democratic establishment in its July 2018 final report was to call for the removal of the Jefferson Davis monument and contextualization of the others. Meanwhile, Richmond’s slave-trading center in Shockoe Bottom—after New Orleans, the second-largest slave market in America; the site of Solomon Northup’s imprisonment and Gabriel Prosser’s martyrdom—was “memorialized” as a cordoned-off vacant lot with a plaque. These events are complex and multifactorial, but Richmonders should at least contemplate, as many Charlottesvillians are, how this came to be and remains.

“A reader of the textbook would not be aware that any controversy existed over integration if this were his only source of information,” Fred Eichelman wrote of the Orwellian Virginia history textbook that is the poster child for American educational propaganda. After years of massive resistance, up to and including closing public schools rather than integrating them, “the whole thing blew up in 1959 when both the state and federal courts ruled that the obstructionist legislation enacted by Virginia was unconstitutional.” The city “supposedly began integrating its schools” in 1960, but the following year, just “37 of 23,000 black students attended white schools.” The denial of history continued for many Richmonders. As one example, according to the school history on the website of private Collegiate School this week:

“The Town School and Country Day School merge[d in 1960], operating on the campus off River and Mooreland Roads. In a “coordinate” configuration, a Girls School [was] formed for grades 5–12, led by former Town School Headmistress Catharine Flippen. The Boys School, also grades 5–12, [was] led by new Headmaster Malcolm U. Pitt, Jr. Elizabeth Burke head[ed] up the coed Lower School. Our first capital campaign raise[d] $1 million to build two classroom buildings, a gym, science building and music building. Included in the funds raised [was] a donation by Mr. [Louis] Reynolds of an additional 30 acres.”

In 1963, the website continues, “the first boys graduate[d] from Collegiate.”

I visited the school’s archives and asked to see the board minutes from the 1950s and 1960s. The archivist told me that he had asked the same question and looked through those minutes. He said there was no mention of race or any reason whatsoever for why a small girls’ school on Monument Avenue was suddenly the beneficiary of a massive capital campaign to build a much larger country school that started to enroll boys. Racism was the driving force, of course, but it was all implied, even in private internal documents. There was an unwritten code that the plainest and most salient fact—Collegiate is a segregation academy—was and continues to be repressed.

It was not written in stone that events from two or three generations ago should maintain omnipotence over the present; conditions in the twenty-first century persisted with the acquiescence and support of modern Richmond. It was not for lack of knowledge or a measure of empathy about the plight of the city’s public schools. Collegiate’s alumni magazine reported on its 2010 Winter Party and Auction at the Westin Hotel:

“In keeping with fundraising for our new library and Academic Commons, this year’s adopted community cause was children’s literacy. Whitney Cardozo, a current parent and Vice President of Education for the Children’s Museum of Richmond, chaired a book drive. Through her efforts and the generosity of the Collegiate community, we collected 10,000 books that have been donated to four schools with whom we have established community service relationships: Oak Grove–Bellmeade Elementary School, William Byrd Community House, St. Andrews School and George Mason Elementary School.”

Certainly, these were not evil people; few in Richmond were. It would be unjust to accuse those who were clearly acting out of genuine kindness to try to soften the edges of a harsh inequity. Yet at some point between the hand-me-down book drive and codified segregation, there was a system that built some children a “new library and Academic Commons” while routinely evacuating an elementary full of equally innocent children rather than fix its dangerous gas leak, and that was evil. The dichotomy of Collegiate’s annual Westin Winter Party and Auction and George Mason Elementary’s “leaking bathrooms, falling tiles and infestations of bugs and rodents” was not something foreign and unchangeable that came down from Mount Sinai. It was a local problem in which real people could make a noticeable difference. It was, in many ways, a symbiosis, created and continued by people who bore varying degrees of moral responsibility for its maintenance.

Reverend Campbell “could not figure out why this place seemed so stuck, or why the values people kept stating seemed to have very little impact on what actually happened. The place seemed immobile,” he stated.

“My current answer to the paralysis of the Virginia temperament that is so exhibited here is that we had a half-revolution in 1783: half the population went into freedom, and half the population went into a totalitarian state.… To proclaim the highest values that had ever been stated in any nation in the world, and to simultaneously practice a horrible level of human oppression is paralyzing to the human spirit. It means you cannot function because you are living with guilt and shame at every moment: moreover, you constructed your society in that way. That paralysis is unadmitted and has continued to paralyze us for almost 250 years.”

There were two Richmonds, wrote Michael Paul Williams, “one ascendant, the other mired in violence and decay.…George Mason and much of the [public] housing stock are remnants of an era we never truly left behind. Even as [other] neighborhoods gentrify and industrial areas such as Scott’s Addition and Manchester morph into eclectic residential communities, Richmond’s public housing and school buildings remain largely frozen in time.” The best definition of the two Richmonds was provided by Joe Morrissey:

• One is public and visible, the other is private and hidden;

• One is largely white, the other is predominantly black;

• One is successful, thriving, and hopeful, while the other is characterized by poverty, despair, and hopelessness;

• One is safe at night while the other suffers from gunfire and violence;

• One sends its children to dynamic, secure private schools, while parents from the housing projects send their children to crumbling, unaccredited, 50-year-old schools.

Joe Morrissey, like many of the people who said they wanted to fix the schools, was running for mayor.

NEW MAYOR, SAME PROMISES

In Richmond’s elections, mayors had to win the majorities in five of nine city council districts. It was one of many unfortunate consequences of Virginia’s legacy that race mattered in elections, but it did, and five districts were majority black, three were majority white, and one was plurality black.

The fifty-seven-year-old Morrissey had spent a career bouncing from personal to professional scandal and back again. He was easy to caricature, but observers were wise not to underestimate his tenacity: he won a state wrestling championship, purportedly two weeks after he tore his ACL; graduated from UVA and Georgetown Law School; and had won election to the state legislature in 2015 when nearly every Democratic official in the state turned out to oppose him. He parlayed a courthouse fistfight into the slogan “Fighting Joe” and adorned his campaign literature with boxing gloves, in case anyone missed the point. It was unusual in any American city, much less Richmond, to see a white lawyer whose substantial base of political support was in the working-class black community. His political acumen was illustrated when he was the sole primary challenger to win against an incumbent state senator in 2019 despite the opposition of seemingly every Democratic official from dogcatcher on up. His detractors had plenty of ammunition but should have conceded that he was a good politician, like a local Trump who turned scorn from the media and establishment opponents into electoral pay dirt.

Morrissey was the frontrunner for mayor and had seemed to overcome a 2014 sex scandal involving a then-seventeen-year-old receptionist at his office. In one of the most surreal scenes in American politics, Delegate Morrissey had served time in 2015 with work release, so that he would write laws in the legislature during the day and drive his Jaguar back to jail each night. He had since married the young woman and claimed he had repented, until it was reported on October 28, 2016, that he had texted a client on Valentine’s Day asking her in Trumpian terms to shave herself. This scandal was a bridge too far for some supporters who may have believed in his redemption story, but he still won 21 percent of the vote and a majority in the city’s two poorest African American districts, good enough for a third-place finish. He surely would have forced a runoff if he could have controlled the Valentine’s Day story (or, better yet, if he had elected not to sext his legal client while his fiancée was taking care of their three-month-old infant).

The leading fundraiser was Jack Berry, the head of a city public-private booster organization. In a city that gave Hillary Clinton 81,259 votes to Donald Trump’s 15,581, a white businessman with Republican ties had little chance of winning. He ended up finishing second with 34 percent of the vote and majorities in the two mostly white districts. Five other minor candidates would garner less than 10 percent of the vote combined.

Morrissey’s scandal was superbly timed for Levar Stoney, the putative runner-up Democratic candidate. The thirty-five-year-old’s “humble beginnings [stood] out among the frontrunners in the race. The child of two teenage parents, he was raised by his grandmother throughout his adolescence and went to public school on free and reduced lunch. He was the first of his family to complete high school, and in 2004 he graduated” from James Madison University after serving as student body president.

Stoney was a newcomer to city politics who had worked his way up through the state Democratic Party to serve as Governor McAuliffe’s Secretary of the Commonwealth. Stoney benefited from being the closest protégé of McAuliffe, who himself was the closest friend of the Democratic couple that many people assumed would move into the White House in January 2017. Stoney raised more than $900,000, just $200,000 less than Berry, and he adroitly used that money to run a professional campaign.

Stoney’s campaign reflected public opinion by trumpeting education as his top issue. He said he would be “the education mayor” and sent out literature stating that “Jack Berry voted for a plan to cut $23.8 million from our public schools,” a claim PolitiFact rated “mostly false.” It may have seemed that the stars aligned for the young challenger who had trailed in every poll prior to election day, but he won 36 percent of the vote while eking out victories in five of the city’s districts. The day after the election, Stoney reiterated: “The number one priority is going to be schools.”

THE VIRGINIA WAY MACHINE

Stoney’s predecessor, Dwight Jones, had also promised reform and investments in schools, but left office with an abysmal 26 percent approval rating after a string of ill-conceived economic development projects had siphoned public funds into private coffers. Compared to other governments, there was not a great deal of money for lavish handouts from city government: Richmond’s annual budget was around $700 million (Virginia’s state budget was roughly $50 billion), and about $170 million was earmarked for Richmond Public Schools. Among Jones’s expenditures were $9.5 million on an international bike race chaired by Tom Farrell that was supposed to make money, $14 million to renovate the Altria Theater, about $15 million to the Redskins camp – another “deal” that boosters falsely promised would make the city money, more than $20 million to Stone Brewery and a proposed $200 million baseball stadium-hotel-apartment development that never got off the ground. In the most salacious example, the FBI came calling when it was revealed that Jones had potentially used city resources to help with construction at a church where he served as pastor. Jones was cleared of wrongdoing after being represented by Richard Cullen, Farrell’s brother-in-law, who is currently representing Vice President Mike Pence.

The criticism of “Stepping Stoney” was that he was unconnected to Richmond and had higher office in mind. During the campaign, he released a glossy commercial showing him running through the city and gazing over it into the sunset. Time had since borne out that Stoney’s election victory had less to do with luck than many assumed, and the young Stoney possessed significant political skills. He spoke the language of someone who would clean up a corrupt Democratic machine. While Jones had negotiated the Redskins deal, Stoney said that “I do believe a city as cash-strapped as we are should not be in the business of writing a check to a multibillion-dollar franchise.” Stoney was also not as beholden to Richmond’s stultified Democratic machine—no church construction patronage from him—yet he seemed to feel that his political ambitions demanded a certain fealty to the monied Richmond establishment that had served as a launching point for many politicians’ statewide political careers.

On June 27, 2017, eight days after Evans released her bombshell story on George Mason Elementary School, “the leader of the superintendent search committee, Dominion executive Tom Farrell, had come out in favor of a $130 million new” local sports arena, a figure that would soon balloon to $300 million and then an astonishing $620 million in public funds.

The money that would be necessary to fund emergency repairs at decaying and dangerous elementary schools was suddenly very much at risk of being siphoned off to private interests in a way that would make the Redskins look like amateurs.

CRUSADER WITH A CONSCIENCE

Into the fray stepped Paul Goldman, who had teamed a decade earlier with Republican political rival George Allen to push historic tax credits—a popular way that President Reagan and a Democratic Congress had conceived to revitalize dilapidated buildings without raising taxes—as a tool for rehabilitating old schools. They had a model: “Maggie Walker High School, built for African-American students during the Depression, was renovated with help from private investors and now houses an acclaimed magnet high school.” Richmond government understood very well how to teach children: the city boasted one of the best public high schools in the country, which was fully integrated and drew children from all over the surrounding counties. Maggie Walker enjoyed widespread support, not least because educating gifted children was probably one of the best investments society could make and private investors made plenty of money from the tax credits. Prior to that, Goldman had worked as Doug Wilder’s top adviser during his stint as mayor of Richmond and had tried and failed to earmark a real estate tax windfall for schools. “If you leave it to the normal vagaries of the politicians, they’re going to spend it on anything but schools, because that’s what they’ve always done,” he noted presciently.

Anybody who had worked in Virginia politics over the previous forty years knew three things about Paul Goldman. As a brilliant young New York transplant, he had masterminded Wilder’s statewide wins for lieutenant governor and governor in the 1980s and cemented Virginia as the first state ever to elect an African American governor. As late as 2019, there had only been one other: Deval Patrick of Massachusetts, elected in 2006. Second, Goldman looked like he lived under a bridge; he resembled the shark hunter from Jaws. And third, Goldman had the rarest of gifts in politics: a sincere, relentless idealism.

Furthermore, Paul Goldman had no ego. “Goldman never wanted office,” Dwayne Yancey wrote in When Hell Froze Over, which remains, with The Shad Treatment, one of the two best books ever written on Virginia campaigns. “If he did, maybe the establishment could understand him better, and maybe it could have bought him off long ago, dispatching him to some far-flung do-gooder office where he’d be out of the way. Nor was Goldman interested in money. If so, he could have cashed in long ago as a political consultant. In a jungle full of mercenaries, Goldman is more of a missionary, a crusading zealot in the game for a higher purpose. He only signs on with candidates he believes in, then pushes their cause with a single-minded fanaticism as unnerving as his ragtag personal style.” He was simultaneously full of intrigue and guileless.

He had been beating a drum for years about the shameful state of Richmond’s public schools. In 2017, Goldman had an unused ace up his sleeve in the power of public opinion. Where top-down reform had not worked, perhaps the will of the voters could in the form of a citizen referendum. Goldman had the wherewithal to do it, having led a successful 2003 petition drive to allow Richmond citizens to popularly elect their mayor. (Critics noted that Wilder was the first beneficiary of this legislative change.) He would launch a petition drive to put the issue before the voters and ask simply that the mayor either come up with a plan to fully fund school modernization within six months without tax increases or else say it could not be done. The first coverage of Goldman’s plan in the Times-Dispatch was in an article by K. Burnell Evans on June 5, 2017—two weeks before her exposé of the rat feces and surgical masks of George Mason Elementary School, and three weeks before Farrell’s Coliseum pitch. (Jeremy Lazarus of the Richmond Free Press first broke the story and has consistently provided the best coverage of the Coliseum scandal.) “This is not aimed at anybody,” Goldman said. “This is about the needs of children who attend inadequate schools.”

Richmond’s political structure did not feel that way. It was no exaggeration to say that its members responded with uniform antagonism to try to stop the initiative from passing and even from appearing on the ballot. If Richmond was a society where politicians reflected the will of their voters, then Paul Goldman would have received a key to the city. Instead, he was targeted with dismissal, whispering, ridicule, and personal and political attacks of every sort—until, ultimately, the politicians acknowledged the wisdom and morality of his ideas and provided desperately needed funds to Richmond’s public schools so the city’s children could have brighter futures.

Mayor Stoney’s actions were mostly behind the scenes, and the public heard their echoes as various surrogates popped up to spout his talking points. In the first response to the petition drive, his press secretary stated that the mayor’s “Education Compact” was sufficient to deal with schools’ challenges. Former Virginia secretary of education Anne Holton quickly came to the defense of the Compact in a Richmond Times-Dispatch op-ed twelve days later, titled “Roll up Your Sleeves, Richmond, for Our Kids and Their Schools.” The Compact itself, which had not yet passed city council, was largely a list of platitudes whose substantive mandate was that the mayor, city council, and the school board would hold joint quarterly meetings. One of the mayor’s top advisors acknowledged that the Compact “doesn’t bind [Richmond’s public schools] to anything.” On June 26, facing pushback from different quarters who saw it as a Trojan horse for privatization, Stoney himself admitted, “There’s no metrics here. No measurements here. All it is is a framework.” “Well, that should fix everything,” retorted the Times-Dispatch editorial board. “I think people want to see some action on this issue,” Goldman noted.

Goldman needed to collect about 10,400 petition signatures from city voters, a daunting figure in a city of just 143,675 registered voters. The 10,400 represented the threshold of 10 percent of the voters who turned out for the previous election, which was a high-turnout presidential year. Considering unavoidable mistakes like duplication, illegibility, and signatures coming from Greater Richmond but not the city of Richmond, the Virginia Board of Elections recommended that signature gatherers collect 50 percent more than the required number. Goldman had his work cut out for him. To give a comparison, presidential candidates could appear on a statewide ballot in Virginia by submitting 5,000 signatures, criticized as one of the strictest requirements in the nation. And he had to get these 15,600 signatures by August 18. Stoney told people that it could not be done.

When Goldman set out to get signatures, he was relentless, as he was when he set out to do anything. Goldman looked like he lived under a bridge because he truly did not have any hobbies outside of political work on behalf of the downtrodden. “Paul Goldman is the most single-minded political operative I have ever seen,” said politico Darrel Miles. “He lives, breathes and sleeps politics seven days a week.” “His metabolism is always teetering on the brink of him falling asleep,” said Ira Lechner, a close friend of Goldman. “He has no visible means of support. He drives a car jammed with stuff. He sacks out at people’s houses. He’s almost like a vagabond. Nobody knows where Paul came from. He just always shows up in different campaigns.” “A lot of other places don’t have the type of person like me who’s crazy and just won’t take no for an answer,” Goldman said. “Thank God I don’t love mountain climbing, or I’d be dead.”

He and volunteers collected 6,619 signatures when registered voters were easiest to find, on primary day, June 13, 2017. This was far and away the most signatures ever collected in a single day in the history of Richmond. One volunteer, a sixty-one-year-old retiree, herself signed up an additional twenty volunteers to work the polls throughout the city. “I did it for the children,” she said.

To complete the task would require a more targeted effort, but the Virginia Department of Elections refused to provide Goldman with a registered voters list. A range of people and organizations, from candidates, to parties, to committees, to voter nonprofits, could access this public document for a nominal $300 fee, yet Goldman and his petition drive group were barred from doing so. Not to be outdone, Goldman filed a twenty-five-page suit on June 30 asking the court for a preliminary injunction against the department, its commissioner, and its board members. “I was right, and they knew I was right,” he said. “What they were doing was unconstitutional. But I settled since I couldn’t get legal fees for representing myself, and I couldn’t spend all my time writing briefs, I had to get those signatures. They gave me the list, and they were supposed to give me my costs back, but they haven’t even done that yet.”

By early August, Goldman had created a citywide campaign for collecting and submitting signatures to the Board of Elections for review. On August 14, four days before the deadline, a Richmond judge certified that Goldman had passed the threshold to appear on the ballot in November. He had collected more than fifteen thousand signatures. “You don’t get a lot of people to sign a petition like this unless there’s a strong public feeling that this is something they want their city to do,” he said modestly.

School Board chairwoman Dawn Page, who had not even responded to an interview request for the first article about the referendum in June, told the press that Goldman’s victory was “good news.” More than that, she was now on board: “Hopefully, it gets the votes necessary in November.” The mayor’s press secretary again released a statement trumpeting the Education Compact as the right path for the city.

With the mountain climbed, the Mayor’s Office was just beginning. The first thing the successful drive did was to prod the mayor into action: the heralded Education Compact passed city council precisely one week after a judge certified the referendum. Three days later, a new gambit was tried. City Attorney Allen Jackson could usually be spotted lounging at city council meetings and occasionally telling the politicians his opinion of what was permitted under the city charter. On August 23, he emailed the Mayor’s Office and city council advising that the referendum violated the charter. Worse news than that, for signatories of the petition, was that Jackson advised the council and mayor to challenge the referendum in court.

The timing of this was striking, to say the least, but Jackson was playing on Goldman’s turf. Richmond City Council members Kristen Larson and Kim Gray—the same two who had sorrowfully looked over dusty school facilities reports in front of reporters—immediately took the bait and publicly advocated for suing. The Times-Dispatch editorial board, which four days earlier had called passage of the referendum “an important symbolic step” quickly piled on, uncritically adopting Jackson’s reasoning that the measure was supposedly illegal. But Goldman, wearing two hats as attorney and operative, was unperturbed. “If the mayor wants to sue, I’ll be happy to beat him. Let’s focus on what matters: fixing up the schools for these kids who have been long denied. It’s time to stop talking and take action.”

The reality of the situation had begun to dawn on observers and opinion leaders throughout Richmond. “This petition gambit is well played,” wrote Michael Paul Williams. “Richmond residents are eager to vent their frustration over the state of the city’s schools, which are viewed as hindering the Great RVA Comeback. Any elected official who opposes the referendum—or questions whether this charter amendment goes beyond ‘the structure or administration of city government’ as opined by City Attorney Allen Jackson—risks being labeled as anti-voter and antidemocratic.”

Councilwoman Larson, who five days earlier had wanted to sue Goldman, explained exactly the box that Richmond politicians were in: “The way it’s being sold is, ‘Do you want to improve Richmond Public Schools with no new taxes?’ Of course you do.” Stoney announced that he would refuse the city attorney’s advice to sue, and no lawsuit came from anyone else. Whereas once the mayor had said that Goldman could never collect all the signatures, he now told people that the measure could not pass in November.

But Goldman had crafted the measure so that it was essentially guaranteed victory if it were to appear on the ballot. Notwithstanding Stoney’s obstinacy, its passage was a fait accompli. Never one to rest on his laurels, Goldman began lining up political sponsors who would shepherd the bill through the state legislature once it passed. Goldman was the former chairman of the Democratic Party of Virginia, yet he could not find a single Democratic sponsor. “The people Goldman really infuriated were those in the Democratic establishment—staid, cautious types who thought they had things under control and wanted to keep them that way,” Yancey wrote. “They don’t just hate him,” said a former colleague. “He’s like an itch they can’t reach. They can’t get rid of him.”

Two Republicans understood the politics and would not be so stubborn. Delegate Manoli Loupassi signed on during his tough reelection battle. So did Senator Glen Sturtevant, who faced reelection in a swing district in 2019. Richmond’s Democratic politicians, and particularly Mayor Stoney, haplessly tried to spike the measure. In early September, Stoney penned the first opinion column that he would write as Richmond’s mayor; he again praised his Education Compact but did not address the referendum. In late October, Stoney and Governor McAuliffe announced a philanthropic initiative to provide vision screening and eyeglasses to all of Richmond’s public schoolchildren. Four days before the election, he blasted a “scathing” letter to the school board criticizing members for not coming up with a plan to fix the schools. In fact, the board had years of plans: lack of funding from the mayor and city council was the problem. The day before the election, Stoney, who was usually a careful and disciplined empty suit, petulantly tweeted that he would not vote for the referendum “on principle.” It was as if Richmond politicians could not comprehend a political operative who just believed in equality; there must have been another angle to it. When Goldman was asked why politicians would oppose a popular measure certain to pass, he replied, “It’s a good idea, it’s good politics, and it works. The only reason I can think of that these politicians oppose it is personal: they convince themselves I’m trying to make them look bad so they go full ‘kill-the-messenger’ mode.”

On November 7, 2017, Richmond voters thwarted the will of their mayor and nearly every other person of power in the city to deliver 85.4 percent support to the referendum, with landslides in every council district and precinct—black, white, rich, poor, young, old, everywhere. “Eighty-five percent is about as close as you can get to unanimity in the political system,” said Goldman. “The people have spoken and sent a message to city leadership.” Yet not a single Democratic politician supported it in an overwhelmingly Democratic city. “Nothing,” said Goldman. “Baffling, really, since I was trying to get them money for their constituents and they still wouldn’t do anything.” That would change.

THE WILL OF THE VOTERS

With public opinion at their backs, others felt free to oppose the mayor and come forward in support of the schools. Delegate Loupassi lost his reelection bid in that year’s backlash to President Trump, and the referendum was briefly left without a lead sponsor in the state legislature. Sturtevant agreed to take the mantle. A week after the landslide vote, Stoney’s spokesperson shifted his claim to a new straw man that the mayor “does not think that we need the General Assembly to tell us how to” fix the schools. Stoney’s intransigence notwithstanding, in mid-November, Democratic Delegate Jeffrey Bourne, a Stoney ally and former Richmond School Board chairman, signed on to lead the bill through the House of Delegates. His explanation was simple enough: “Eighty-five percent of the people said they want the charter changed, and it’s our duty to do what the people want.” The Richmond NAACP had sat out the signature-gathering and did not activate its political operation to turn out the vote for the referendum. So, too, had school board members, who had their own bases of support as well as a public platform to call supporters to action. They had been in office for nearly a year and had failed to present a facilities plan, until they presented one two weeks after the referendum and passed it two weeks after that. A month after the landslide election, the head of the Richmond NAACP and five school board members held a press conference outside of George Mason Elementary School to call on the mayor and city council to find $158 million to bridge the gap between what the board had asked for and what they received for upgrading Richmond school facilities. “We have a plan on the table and what we also have is the city made a statement in November: we want to make change,” said board member Kenya Gibson. “We’ve had plans again and again, and nothing’s happened. Now, we have to fund the plan.”

Mayor Stoney sat down with the Richmond Times-Dispatch for a reflective interview at the end of his first year in office. His much-touted Education Compact had accomplished nothing except for quarterly meetings between the mayor, city council, and school board. Within six months, those meetings would devolve into internecine squabbling and become sparsely attended. Stoney proudly noted that he had visited all forty-four district schools and had launched the eyeglasses initiative. These were helpful palliatives, but after an entire year, Stoney had little else to show. The gap between the image the mayor wanted to project and the reality of his administration was growing.

No politician can resist the will of the voters forever. After their voices sounded loudly at the polls, the recriminations of 2017 would rapidly give way to meaningful change. With the inescapable 85 percent vote, the political system in Richmond had shifted underneath the mayor’s feet.

The first sign of change was when Delegate Bourne submitted a different bill to the House, one that would modify the referendum language to permit a tax increase to fund schools. “The mayor believes Delegate Bourne’s version is an improvement,” said Stoney’s spokesman. Sturtevant’s Senate version of the bill remained identical to that passed by Richmond voters. Bourne’s bill died a quick death in a House subcommittee, where the chairman coolly “told Bourne after the bill was killed to ‘take a good look’ at the Senate version.” The next day, Sturtevant’s bill passed unanimously through the full Senate, and less than three weeks later, Sturtevant’s bill passed through that same House subcommittee unanimously. On its way to passage, the bill would not receive a single vote against it from any politician in the state. Governor Northam signed the bill into law on April 4, 2018. “Stoney repeated his objection,” a reporter wrote, “saying that putting the referendum on the ballot is easy, but finding funding is the hard part.” “After 62 years of being denied, the children of Richmond will finally get a plan,” Goldman said. Levar Stoney had been checkmated and, for no reason other than spite, had opposed a measure that 85% of his voters and every other politician in the state supported to adequately fund Richmond Public Schools.

IN ACTION

The inaction on schools that had distinguished Stoney’s first year would not characterize his second. Delegate Bourne’s legislative ploy in mid-January augured a more public effort by the mayor to actually use his substantial political capital. On January 23, 2018, Stoney announced a proposal to increase the city’s meals tax by 1.5 percent to fund school facility needs. The revenue would be earmarked for a $150 million bond issue for schools that would fulfill the school board’s request. That same day, he gave his first State of the City address and made the meals tax its hallmark proposal. He telegenically held up two pennies. “One and half cents—for our children,” he said to applause. “Less than these two pennies I have in my hands.”

It was an unexpected play. During his 2016 campaign, Stoney had offered a vague sentiment that cigarette taxes should be raised in order to lower businesses taxes and protect the city’s bond rating but had not offered anything concrete.

Regardless of where the public stood on schools, there was at least a case to be made that the meals tax was not the best way to pay for them. Some restaurant owners would naturally be opposed; on the other hand, some people claimed that they would dine out even more in order to support schools. Some restaurant owners publicly supported the tax. Others noted that, given city hall’s history of corporate welfare and cronyism, there was unused money to be found in the budget. City council was initially uncertain, and the first vote count stood at two to two, with five undecided. Political power in the restaurant community was diffuse. A vote count a week later showed that three members of city council now supported the proposal, with four undecided. Stoney praised and cultivated restaurateurs in press releases and photo ops. It was a difficult position for them to be in, and they could not come up with a winning argument. “We know that there is a problem with the schools, we know they need to be fixed, and we know restaurants should not be the one bearing the full cost of that burden,” said Frank Brunetto of the Virginia Restaurant, Lodging and Travel Association. The meals tax was approved by a 7–2 vote of the city council on February 12, just twenty-two days after Stoney’s State of the City speech. “By city government standards, Stoney’s proposal has moved at warp speed,” a reporter marveled. The $150 million would pay for replacing George Mason and another elementary and middle school that were among the worst in Richmond’s portfolio. The alacrity of his successful meals tax push demonstrated what Stoney was capable of accomplishing when he wanted. It was an important start, but as a result of decades of neglect, there was another $650 million to go until all city schools were modernized.

Stoney’s obstinacy never permitted him or many on city council to acknowledge the referendum as a driving force, but money began to turn up for schools where there had supposedly been none before. Readers of the Richmond Free Press were presented with a striking juxtaposition between the May 4, 2018 headline, “No More Money for School Maintenance” and the August 16, “More Money Found for School Maintenance.” The source of the money was never fully explained, but apparently, an additional $9.5 million turned up when “city and RPS departments reconciled their school capital maintenance and construction accounts.”

FIELD OF SCHEMES

It was as if a parallel universe existed in the other Richmond, where “a shadow government of big business chieftains, lawyers, bankers and planners relentlessly tries to push things its way.” At the same time that school emergencies were banner news, the other Richmond sought to hamstring the city’s ability to finance school construction for future generations by earmarking public money for private pockets. June 2017 saw the triumvirate of Goldman’s referendum, Evans’s seminal article, and Dominion CEO Tom Farrell’s $1.4 billion urban renewal proposal. As news of the latter emerged, its inconsistencies quickly began to pile up into a shaky house of cards that revealed the true intent.

The details of the proposal were vague and kept out of public view. They were negotiated behind closed doors between Stoney’s office and what was often euphemistically referred to as “the business community,” essentially a handful of establishment Republican CEOs of Richmond companies.

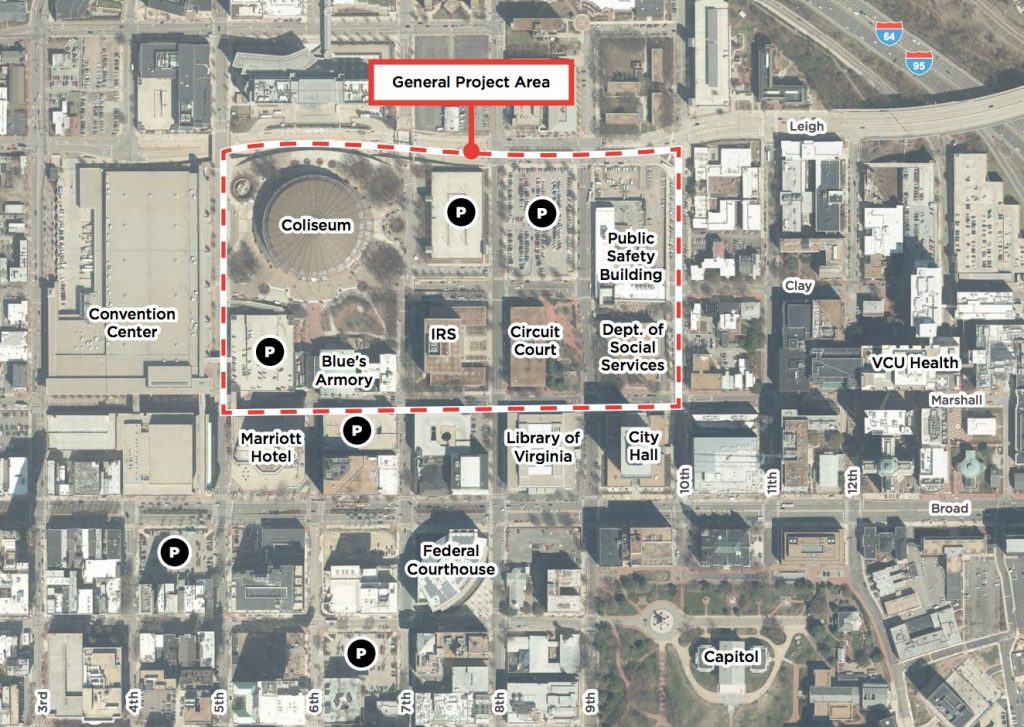

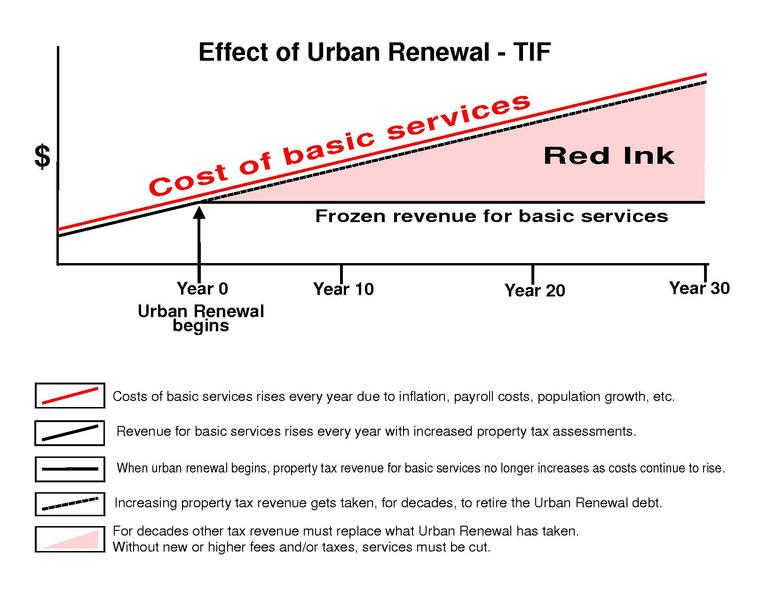

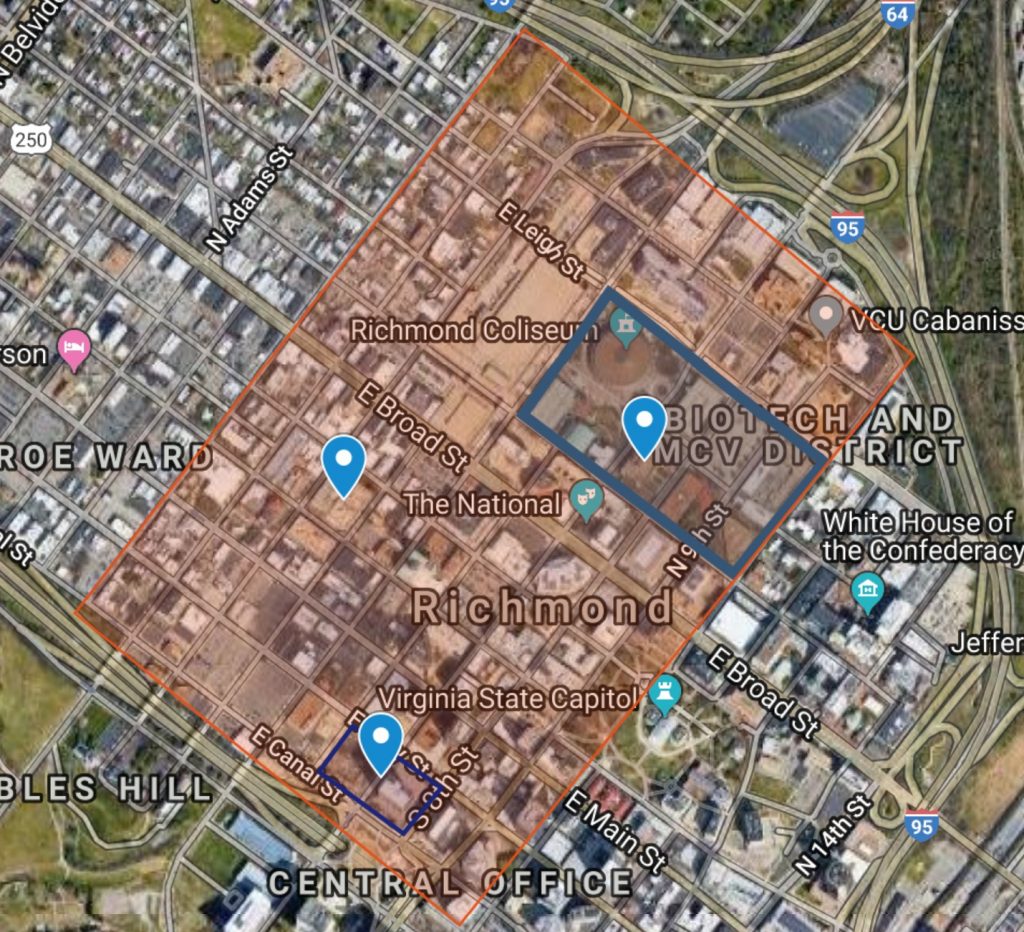

The same people were always behind ostensibly civic projects that had been pushed for decades, usually to the detriment of the public coffers. The Coliseum proposal reconstituted the business-political alliance that had led to boondoggles such as the despised Redskins deal. In the most recent iteration, the business community shifted the location of a proposed public-private megaproject from the Boulevard and Shockoe Bottom areas to the Richmond Coliseum and replaced Mayor Jones with Mayor Stoney. Dominion’s other lead on the project besides Farrell was Dominion spokesperson and Jones’s former chief of staff, Grant Neely. (This week, Ralph Northam cut out the middle man between his office and Dominion’s propaganda by naming Neely as his own director of communications.) The lynchpin was replacing the Coliseum, built in 1971, with a larger arena, which would be financially successful for some unstated reason. The project would be funded by tax increment financing, whereby any tax revenue collected from an area above current revenue levels would support thirty-year construction bonds. Real estate appreciation would naturally increase the value of the project zone by three or more times over thirty years; inflation alone would double it. Those taxes would flow to the city anyways, but they would now be dedicated by law to private investors. The arena would be joined with a new hotel and apartment building that would replace a federal building, the city courts, a few parking lots, and two buildings hosting a variety of city functions such as social service and job agencies.

Jeremy Lazarus of the Richmond Free Press pointed out that these city facilities would have to move somewhere, but during the first year and a half the proposal was under discussion, it was not mentioned by a single person where those federal and city offices would move. Only in late 2018 did it begin to come out that the social services building would move to an out-of-the-way former Altria operations center with sporadic bus service six miles down I-95. It is still not mentioned what will happen to the thousands of people in the large IRS building, why in the world the federal government would pay the tab for their relocation, and if anybody had even asked.

This precise area had been the focus of at least four big-ticket urban renewal projects over the past sixty years, about once every fifteen years as if on schedule. Richmond had a relatively small budget and strict debt limits that were lavishly tapped four times for these projects, and which failed four times in a row. The original sin was to bulldoze the prosperous area of town known as “Black Wall Street” to build the I-95/64 highway in the north corner of the map. That destroyed and hollowed out the neighborhood. Secondly, the unsightly Richmond Coliseum was built in 1971 with $16 million in taxpayer funds; it had since received millions more in public subsidies, including $7.1 million in renovations in 2003. In the 1980s, the Sixth Street Marketplace at Sixth and Broad cost more than $30 million in city bonds and opened to much fanfare; retail tenants in the Blues Armory slowly left when customers failed to materialize. The frontispiece was a pedestrian bridge crossing Broad; the bridge and much that remained of the project was razed at the cost of an additional $800,000 in 2003. The Convention Center cost more than $170 million in city and country funds in the early the 2000s. Its backers, too, had promised that construction would develop what was now suddenly in need of redevelopment. “Time after time the city commissions some consultant, many of whom I know and respect, to provide gaudy numbers on how one project or another will pay back the taxpayers, but none of these publicly funded land deals ever end up working the way they were sold,” concluded School Board member Jonathan Young.

The area slated for renewal was adjacent to the expanding VCU Medical Center, and it was striking to see what could only be described as willful amnesia amongst ‘the business community’ about what had taken place within the last few years. The cornerstone of Mayor Jones’ Boulevard redevelopment project was building a children’s hospital with the help of a generous $150 million pledge from local philanthropist Bill Goodwin. One of VCU’s main objections was that the Boulevard was five miles away from the medical campus that hosted hospitals, clinics, offices, and dental, medical, nursing, and allied health schools, and would thus warrant inefficient duplication of many facilities and services. None of this happened in a minor footnote somewhere: an entire forest probably gave its life for all the press coverage of that unsuccessful idea, and Goodwin himself was a member of the Coliseum group. Now, all of a sudden, the very parcels not available to VCU to build a pediatric hospital because they housed critical government services were suddenly free for the taking if Hyatt would build a hotel there with the help of public funds.

Furthermore, the area was not some ghost town that nobody visited, and it was astonishing to hear it repeated again and again that the area was some variation of an “urban wasteland,”as the Richmond Times-Dispatch editorial board opined. The board had seemingly forgotten its prior take on sports arenas, which it had lambasted for costing the city perhaps $15 million. “Whatever publicity Richmond might be getting out of the [Redskins] deal can’t begin to stack up against the need to improve Richmond’s schools,” its members had written. “Fixing them would do more for the city than any sports or entertainment offering possibly could.” “In a city that claimed to worship history,” the most important truths were unmentioned because of Richmond’s cognitive dissonance about plain facts; the area north of Broad Street had been historically black, and south historically white. There was still some of that segregation today, especially in housing, but the VCU Health campus and surrounding government areas were probably the most integrated and accessible places in the entire city: everyone got sick or had to go to court or City Hall at some point, after all. There were plenty of people in the area slated for ‘redevelopment:’ Richmond was a majority black city, and maybe two-thirds of the people in this area at any time happened to be African-American residents just living their lives.

Yet Richmond’s Chamber of Commerce leaders penned their feelings about it in Richmond’s inimitable coded language: “Do we want the space between the VCU Medical Center and the convention center to become a walkable, attractive area filled with residents and visitors or do we prefer blocks of unattractive old office buildings that encourage folks to stay away?” “Folks” did not “stay away:” even in the map above that the city submitted in its request for proposals, one can see hundreds of cars in mostly full parking lots. Thousands of people worked and conducted business there everyday, despite the Chamber leaders’ evident fear to even walk in the area.

Ben Campbell noted the conspicuous factor in the psychology of many Richmonders:

“We had a study about twenty years ago where the Chamber of Commerce went to Richmond’s peer cities in the mid-Atlantic – Memphis, Charlotte, Greensboro, High Point – and found that of the cities they studied, Richmond had the lowest crime rate and the highest fear of crime. This is just me, growing up in Virginia, but I think that if you are busy keeping other people down and making a lie of the values that you state, that basically you are afraid of them, because you know that the people you are harming want to get you, or you think you know they might want to get you. If you read the stories of Richmond, there is constant fear of black people.“

There were two projects in recent years showing perhaps the most important motive for the project. Kanawha Plaza in downtown Richmond was closed for much of 2015 and 2016. The supposed impetus was sprucing up the city like a Potemkin Village for the September 2015 UCI Bike Championships, but the Plaza was a longtime encampment for the homeless, and it was closed during the race. In August 2015, a representative from Enrichmond, another group representing the same business community, pledged to city council that an unnamed group of private backers would provide $6 million to bulldoze and rebuild Kanawha Plaza. He asserted, falsely, in response to a question from Councilman Agelasto, that the names of these backers had to be revealed in the nonprofit’s annual 990 tax forms. That never happened and never would happen because that money was never there, and that information was not and could not be publicly disclosed in 990 forms.

As of this writing, the financial backers of the Coliseum project have also not been revealed, if they even exist. It is highly dubious, at best, to consider that ‘the business community’ would have $900 million cash to invest in this project, and that, therefore, that money has been waiting for this golden opportunity for at least two years. Regardless, after the Plaza was bulldozed, the phantom backers withdrew their commitment and left city taxpayers on the hook for reconstruction. It was re-engineered as an anti-homeless park: it looked mostly the same, but structures like a pedestrian bridge and trees were destroyed. Areas where poor people would congregate were redesigned to prohibit sitting, and embankments were studded with metal plates so that people could not lie down. From 2016 to 2018, the target of urban renewal was Monroe Park, where homeless people also gathered, and its makeover bore the same hallmarks. It was closed for a couple years, and the city threw a lot of money at it to make some cosmetic changes. Monroe Park had been imperfect but functional, and $6.8 million in renovations, with about half coming from the city, was a great deal of money. The budget for Richmond’s homeless services in 2018 was roughly $500,000. The renovations also removed most of the park’s benches and added a police substation. When the park reopened, the homeless had disappeared.

There were a handful of homeless people who also lived in the Coliseum area, and the city’s cold-weather homeless shelter was in the Public Safety Building. The city began looking for a new cold-weather shelter away from downtown in late 2018. It was not like spending all this money actually solved the problem; it merely displaced one or two dozen people so businessmen would not have to look out their windows at them. Rather than inventing urban renewal projects to wipe out the problem, it would have been cheaper to invest in decent services and schools to prevent the perpetuation of desperate poverty.

It was not clear if there was a good reason for the Coliseum even to exist, argued Lazarus and Style Weekly’s Jackie Kruszewski. There was a problem with the outdated Coliseum and its $1.75 million annual subsidy from the city that could be solved by selling it on the free market. During this time, Richmond was going through a commercial real estate boom and had no problem attracting hundreds of millions of dollars in private investment. The city valued the Coliseum parcel at $12.3 million and could have easily opened the area for competitive bidding; this would undoubtedly be the path that would generate the most revenue to fund city services and schools.

Instead, the captains of industry who usually trumpeted capitalism wanted to distort it with cronyism, just as they and their forebears had mismanaged development of the area for decades. It was difficult to understand how the four-block Coliseum parcel would suddenly become filled with more people during the day if it were replaced with a larger arena that would also necessarily hold events only at night or on weekends. But some of the business community’s motives were highly questionable, at best. In 2007, many had banded together as the “gang of 26” led by Farrell to try to abolish Richmond’s elected school board. Farrell had also used $1 million in public money in 2014 – not 1914 – to make what one reviewer called a “contemptuous” Confederate movie in which Lincoln and Grant conspire to murder children.

Farrell was a member of the Gray family, whose patriarch had sat on the Dominion board and who bore as much responsibility as any Virginians for massive resistance. It was difficult to maintain with a straight face that the four-block Coliseum parcel would suddenly become filled with more people during the day if it were replaced with a larger arena that would also necessarily hold events only at night or on weekends. “It comes up in every meeting: this can take Beyoncé,” said the investment group’s spokesperson, Jeff Kelley.The indelible image for the schools crisis was teachers wearing surgical masks to teach in Richmond’s true “urban wastelands”; here, the indelible image was a group of clueless old men stoking each other’s egos with thinly-veiled entendres and repeating, “if we build it, she will come.” It was absurd, of course, but Richmond is run by provincial people with very small minds.

None of this was to stop the group from race-baiting, for example, by trumpeting that the proposal included “$300 million in contracts for minority-owned businesses,” a patently illegal racial quota under the U.S. Supreme Court’s Richmond v. Croson, in which the Court ruled that precisely $300 million in minority set-asides was unconstitutional. A number of provisions in the legislation submitted to City Hall allows the developers to delay or shirk their responsibilities if the legislation is challenged in court, is found to be illegal, or the city delays it for any reason.

Stoney kept mum about his thoughts on the proposal while he openly opposed the school referendum. An October 2017 poll showed that 64 percent of Richmonders supported paying more in taxes for schools, while 65 percent were opposed to using public money on the Coliseum project.

Amazingly, just two days after the 2017 elections and referendum, Stoney held a press conference to announce “his” request for proposal (RFP) on a development project that was nearly identical to the one proposed by ‘the business community.’ “I am well aware of their ideas,” Stoney said, “but this is a city of Richmond project.” The RFP differed little from Farrell’s proposal except to call for a rebuilt bus transfer station and affordable housing as part of the new apartment complex. “I prefer competition,” Stoney said. The extent of the competition was clear when the RFP closed in February and only one group submitted a proposal: the same group that had initiated the RFP.

“Our city made it clear that our priority should be our schools, and I agree,” School Board member Kenya Gibson said wistfully.

The financial numbers behind the proposal were impossible to believe. Tax increment financing was itself a disingenuous ploy. As noted, any real estate in downtown Richmond would appreciate over the course of thirty years; earmarking this revenue toward a bond proposal would starve the city of resources and was no different than raising taxes by any other means.

A new arena would cost around $220 million and “over 30 years would require an annual payment of $11 million to $22 million a year, depending on the interest rate;” the taxes on such an arena would amount to just $2.4 million yearly. “Several developers the [Richmond Free Press] consulted and who spoke on condition of anonymity could not fathom how a private coliseum could generate enough income to cover debt, let alone generate a return on the investment,” Lazarus wrote. The bottom line for the new project began at $1 billion in total investment, but, as time went on, that grew to $1.4 billion, and the money that the public would put up went to $300 million, or $620 million with interest, nearly the cost of completely modernizing all of the city’s schools. The proposal took time and money from such efforts: by September 2018, the city was canceling scheduled events at the arena and had spent nearly half a million dollars just reviewing the single proposal. “I can’t wrap my mind around half a million dollars for studying a Coliseum deal that we haven’t even had a public conversation about as council,” Councilwoman Gray said.

Richmond City Council and the public continued to be kept in the dark about any details, but the public got the best look at the cronyism and unstable financing of the proposal in documents uncovered by reporter Mark Robinson. The project would now be funded by tax increment financing as well as the taxes from Dominion’s downtown office buildings, which were so far away from the project that they do not even appear on the map the city submitted in its proposal. Unbelievably, Farrell “said it’s just a coincidence that Dominion’s new tower is part of the proposal.” He must not have checked with his public relations team, because spokeshack Grant Neely claimed in another article that “it’s the closest taxable property to this area.” This was patently false: there were dozens of taxable properties from small and large businesses to apartment buildings to hotels that were closer. “If that is the proposal, that would not be palatable for me,” said City Council President Chris Hilbert, who deemed it “troubling.” Chris Hilbert’s tenure on Council was most distinguished by continually preaching fundamental principles time and again about how he would not fall for a bad deal for the taxpayers, then folding when it came to the final vote.

As tenuous as those numbers were, they seemed almost reasonable compared to other aspects of the deal. The purported projections for arena revenue seemed to be invented out of whole cloth. The group claimed that it would “generate $3.7 million in revenue to help cover debt service payments in its first year in operation, and $5.8 million by its third year.” However, the “nine comparable arenas” that the group cited “made an average of $953,000 annually. The highest grossing venue brought in $2.9 million.” The group also claimed that meals tax revenue from new restaurants in the area would not displace meals tax revenue from other restaurants because, they claimed, the only people who would eat in the area would be new tourists and new residents. Staid and independent experts looked through the details and raised a number of serious red flags. Esson Miller, the former staff director of the Virginia Senate Finance Committee, wrote that the businessmen were “rummaging through the city’s fiscal well-being, putting it at severe risk that could have long-term detrimental impact.” Analyst Justin Griffin found that the modeling assumed that every attendee at a Coliseum event would spend an average of $458.48 on popcorn, candy, and so forth. The capstone of the deal called for transferring these properties to the investment group for 99 years, a giveaway usually seen only in kleptocracies. Farrell had pledged that he would not see any money from the project; the electricity for the new businesses and residents would be provided by Dominion. Stoney, who well knew about the damning details that demonstrated the project was not on solid financial footing, was left in a bind and discarded his usual careful rhetoric. “This is our project,” he said. “This is not Dominion’s project. It’s not any other entity’s project. This is our project. This is my vision. … I don’t care if it’s Tom Farrell or Johnny on the street, if it does not benefit my city, this project will not move forward.”

The fantastic veered into propaganda at the headline claim Stoney repeated like a chorus that this would somehow create 9,000 permanent jobs. A $1.4 billion investment spread over thirty years worked out to about $47 million per year, or about $5,100 per year for every “permanent job.”

In any event, most of the cost of the project would be spent on materials, not labor. To give an example that backers should have been familiar with, Dominion employed about 16,000 people and had about $12.6 billion in revenue annually. It was a 100 percent certainty that this project would not possibly create nine thousand permanent jobs and might actually increase unemployment through hiring fewer teachers, firefighters, and cops.

IMITATION AND FLATTERY

Stoney was a Clintonian public figure, in the best and worst senses of the word, though his personal life was far less tarnished. The conclusion of this story so often in Richmond’s history was that the people who owned the city’s private resources also controlled its government. Smart money was on “the business community” co-opting yet another politician, but Stoney was seemingly not as malleable as his predecessor. In August 2018, Stoney called a reporter to tell him that Farrell’s proposal was not yet living up to his goals on affordable housing and briefly stalled the negotiations. The trepidation that his designs on higher office would cause him to ignore the city may have been misplaced; the fact that he would need a base of voters for the future could instead serve as a corrective. Stoney was barely elected; Mayor Jones had pursued the same policies Stoney was pursuing and left office with the popularity level of Richard Nixon. There was one reality that proved more indelible than schoolteachers’ masks, grandees’ Beyoncé fantasies, or any opinion poll or political theory, and that was that 85% of Richmond voters wanted him to fix the schools.

In mid-October 2018, Goldman announced that he would pursue a second ballot initiative, “Choosing Children over Costly Coliseums,” that would require that 51 percent of money from any tax incremental financing in the city go toward modernizing schools. He had nine months to collect signatures—nine months to let the vote sit like a sword of Damocles over the mayor’s political future. “Levar Stoney should have known better than to play political chess with a grandmaster like Paul Goldman,” Style Weekly concluded.

Stoney penned an opinion piece in late October 2018, not for his city, but for his hometown Virginian-Pilot:

“Many of our school buildings are well beyond their lifespan and are literally crumbling. They are no longer the safe, healthy environments our students need to thrive. But these facilities are just one part of the education crisis facing us today—our entire K-12 education system is woefully underfunded.…Failing to provide for the most vulnerable among us today is not just unacceptable, it is immoral.”

He called on Virginians to join him in marching on the state capitol on December 8.

On November 1, 2018, Stoney unveiled the program that he had kept under wraps during months of secret negotiations. It made a lie of all the financial promises about how “additional” revenue would pay for the construction in the eight-block zone. The TIF district would be expanded from eight to eighty blocks, encompassing essentially all of downtown Richmond and all of its office buildings between First and Tenth Streets and I-95/64 and I-195. The area east of this zone was largely VCU and government-owned, and thus untaxable. Under this program, the additional money that would be needed to pay for citizens’ schools, police, firefighters, snow removal, trash pickup, and all the other vital services that cities needed to function would for at least the next thirty years be earmarked to paying back private investors.Goldman’s referendum would mandate that 51 percent of any TIF revenue go to schools; under Stoney’s plan, only 50 percent of “surplus” revenue after bondholders had been paid back would go toward schools and public services. The problem was that the corrupt Stoney-Farrell machine could lie to the public all they wanted, but they could not get banks to issue bonds that would clearly fail, as they would under the originally proposed plan. In short, they had to pay the banks and private investors, and they had to mortgage the future of the city to do it.

Sixty years ago, Richmond’s power brokers had bulldozed neighborhoods and endowed schools like Collegiate to prevent integration, but they had never dreamed of effectively annexing the city’s financial district. The Stoney-Farrell project consummated the final dream of massive resistance by taking the most lucrative and stable revenue source for the city and turning it over to wealthy businessmen for the remainder of this century and beyond. So far as can be determined, no city in the history of the United States had ever done such a thing. There was no precedent in Virginia since long before the Revolutionary War; one had to go back to the Virginia Company of London, when King James would simply decree that common land belonged to whomever he wanted. In this case, the role of King James was played by the largest campaign donor in the state. It was indescribable.

On December 8, 2018, Stoney led a march of more than a thousand people on the state capitol to call for more funding for education. He said to the crowd:

Each and every day, there is a young man or a young woman who wakes up with a dream, and it is our job—as elected officials, as teachers, all working together—to give them the legs to stand on to achieve that dream.

The public, reporters, and fellow politicians were coming to realize the Levar Stoney was neither an empty suit nor a puppet: he was a con man. There was just as much construction money to be made from building schools as there was from building an arena; the choice to pick one over the other was a moral judgment. Any support for Dominion’s racist Coliseum scheme came only from those who were bought off.

Whereas Stoney had flashed a smile and easily gotten city council to raise taxes for schools earlier that year, city council bucked the mayor for the first time in an 8–1 vote in mid-December 2018 to establish a commission to review financial details of the increasingly dubious proposal. In January 2019, the majority of council members rejected Dominion money or any donations from Tom Farrell. Days later, Stoney made what could only be described as a deliberate insult to his own voters by submitting a two-page non-binding “plan” that he claimed met his obligations under the referendum.

MANIPULATING THE RICHMOND TIMES-DISPATCH TO PUSH COLISEUM PROPAGANDA

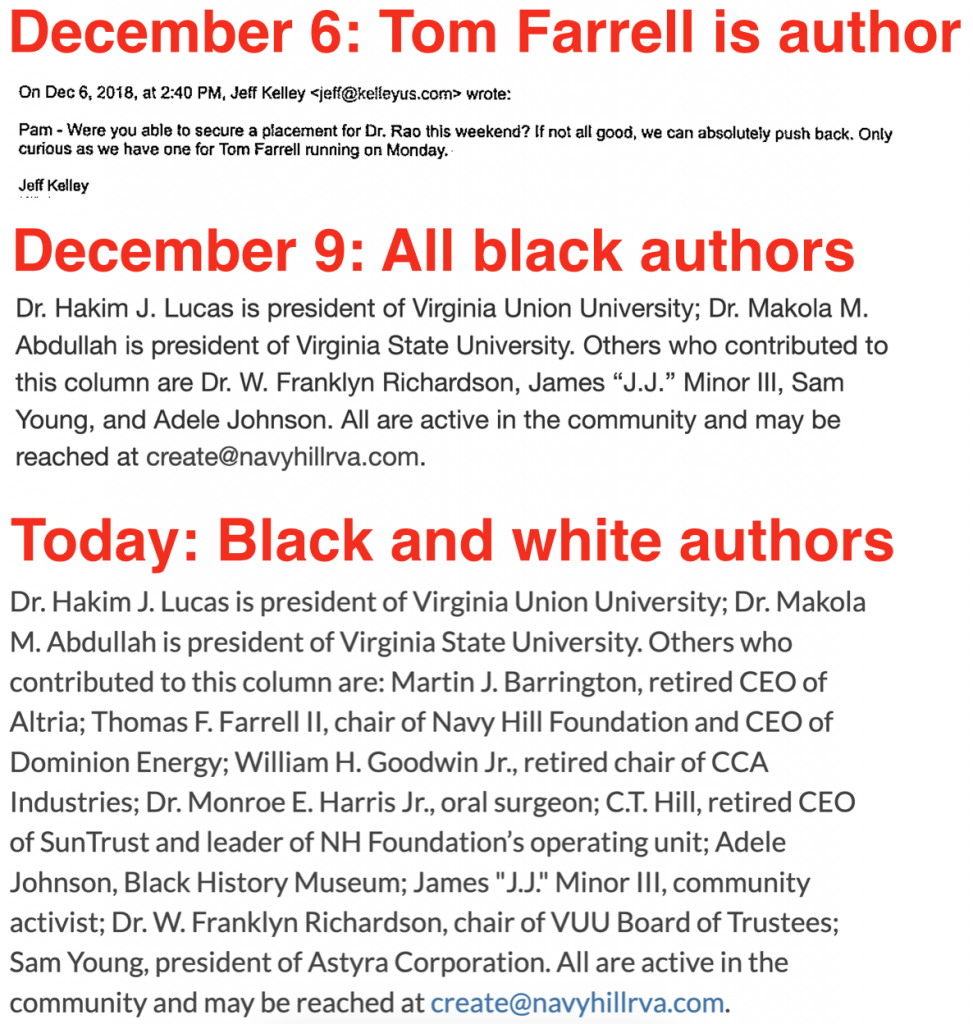

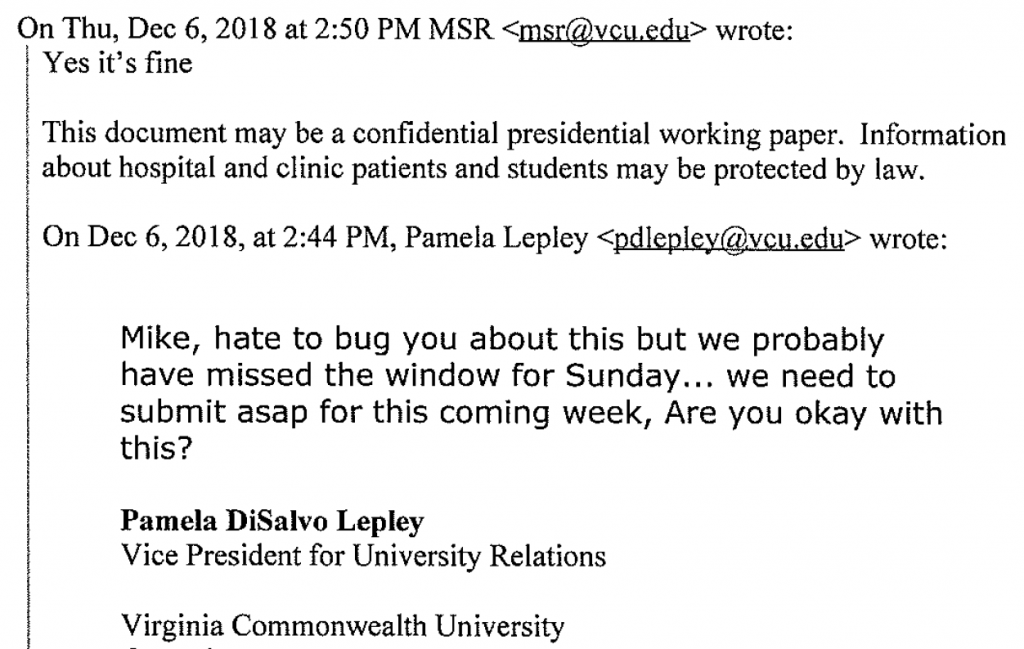

The people behind Dominion’s Richmond Coliseum scheme do not care about the public except as an impediment to their unilateral control of public money. They well know the problems facing Richmond public schools were caused by segregation, underfunding, Massive Resistance, and racism: their solution is to try to abolish the School Board and take away people’s right to vote. The free press, too, is an instrument of citizen democracy, but by mid-2018, the extreme level of deception in the Dominion Coliseum scam had begun to appear on the front pages, and the lies were no longer tenable. In response, in late 2018, Dominion officials and the wealthy autocrats who ran the front group NH District Corp. manufactured a campaign to disseminate corporate propaganda on the op-ed pages of the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

There is an inherent tension between news reporters and editorial boards. News reporters are rightly constrained by the conventions of journalistic ethics, interviewing and language, while editorial boards have much more freedom, and, ironically, influence.