by Kellen Squire

I’m sure I don’t have to belabor the point on the need for healthcare reform in the United States of America. While things seemed to be improving throughout the last decade, the past two years have seen a dramatic reversal of the meager successes the Affordable Care Act (ACA) brought. The most prominent of these reversals has been in decreasing the rate of uninsured Americans through both private health insurance managed with subsidies, as well as through programs like Medicaid expansion, which aimed to address the “doughnut hole” where working families were penalized for working too much to qualify for Medicaid, while not making enough to qualify for subsidized premiums.

While a segment of politicians has cheered the calculated sabotage of these programs, usually under the guise of fiscal concern, this has always been nothing more than a charade, an epic gaslighting of taxpayers for the sole purpose of political expediency. This is because of a law called the Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act (EMTALA), passed in 1986, that has, for the last thirty plus years, meant that the United States of America has effectively required that universal healthcare be provided to every single person within its borders. However, it’s just been mandated to provide that care in the least efficient and most costly way possible.

EMTALA ensures public access to emergency services regardless of ability to pay, with severe repercussions for institutions that do not comply with the law (up to and including forfeiture of all reimbursement from Medicare funds). While certainly well meaning- to stop the epidemic of people dying or giving birth in the streets, since pre-EMTALA hospitals could turn away anyone without the ability to pay- most estimates suggest EMTALA has cost taxpayers and consumers literally trillions of dollars since it was signed into law by the bipartisan 99th Congress (Democratic House, Republican Senate and President Ronald Reagan) due to both the provision of unreimbursed care and because of patient decompensation (as health conditions deteriorate until they become an emergency).

If you’ve ever heard the example “a Tylenol costs $900 in the hospital,” EMTALA is the reason why.

But you’ve never heard a politician suggest we should eliminate EMTALA and go back to the pre-EMTALA time when patients were turned away after being denied treatment at hospitals for inability to pay. Instead, they count on buzzwords and voters who are too busy or unfamiliar with arcane medical laws that even most healthcare providers struggle with understanding fully. They know that repealing EMTALA is not only impossible, but would be political suicide. Instead, as mentioned before, people who seek care and cannot pay for it simply have their costs shifted to everyone else instead via the axiom “there ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.”

This was actually the genesis for the “no free rider” caveat to “Romneycare,” the cutting-edge solution crafted by the Heritage Foundation to address healthcare reform. Mitt Romney famously pioneered this approach in Massachusetts in the mid-2000s. It was heralded widely as a forward-thinking piece of legislation, which ended up not being too far removed from the truth. Romneycare was effectively made a centerpiece of the healthcare reform package that became the Affordable Care Act. This happened, even though in many ways the ACA was actually more conservative than Romneycare, as Democrats tried desperately to purchase Republican support for the bill during the 111th Congress.

While that is all pertinent information, it’s there merely to give you some background on EMTALA and the discussion around healthcare reform related to it. What matters is that nationally in 2016, almost $40 billion in uncompensated healthcare was charged in the United States of America ($38.3 billion), and while exact numbers are hard to come by, Virginia’s slice of that was something in the range of $1.1 to $1.5 billion.

But again, that billion-dollar amount doesn’t evaporate into thin air- it’s still paid. It’s just paid for by everyone else who accesses the system. This is something that should be emphasized: the genesis of that $11,000-per-capita healthcare cost for every American.

To put it bluntly: We’re paying for universal healthcare, RIGHT NOW, and getting screwed in doing so. I don’t know about you, but I hate getting screwed.

I hate paying more for care than any other country in the world, by a LOT, and having worse outcomes! I hate that we’re forced into this situation by legislators who don’t have to worry about things like co-pays, the instability of losing coverage, or wondering how much of a visit might be covered if something goes wrong. I hate, as a nurse, that politicians count on my colleagues and me to hold the line, taking care of people who can only truly seek care once they reach crisis status, instead of well before that. If we want to fix it, if we want to pay less and get more, we need to work toward comprehensive healthcare reform.

But there are dangers herein that we need to be aware of.

THE DANGERS OF MEDICARE FOR ALL

Medicare for All (M4A) is probably the best way to fix our broken system. I say “probably,” because while I’ve yet to hear a compelling alternative. As a medical professional, I’m driven by peer-reviewed, evidence-based research. Both Romneycare and the Affordable Care Act were far from perfect, but they established solid progress in extending healthcare coverage to Americans. And, as a nurse, I want to see my patients served the best way we can possibly get. With all that in mind, I am open to hearing anyone’s ideas on how to address this. That being said, Medicare for All is by far the best idea I’ve heard to date on how to address this.

However, although M4A is the most commonly spoken of plan to address this – and while the details of what would be in a “final” bill that gets passed differ somewhat from proposal to proposal – there’s a bottom line that we’re not paying enough attention to:

If something like Medicare for All gets passed tomorrow, the Commonwealth of Virginia simply does not have enough providers – doctors, nurses, NPs, PAs, psychiatrists, EMTs, etc., etc. – to provide the backlog of care that will suddenly be covered and requested.

As my good friend Rebecca Wood, healthcare activist extraordinaire, likes to say: “Insurance is not access.”

What this means is that places like emergency rooms across the Commonwealth will be slammed indefinitely until we get it fixed- which isn’t an answer, of course. Although these people will finally be receiving care, it will be in the place that provides the most inefficient care of almost anywhere in the healthcare system. The emergency department is supposed to be primarily concerned with saving lives, and, as such, it will almost always be more inefficient and expensive than other modalities of care.

We have a crisis right now, with staffing levels amongst medical providers at all levels a fraction of what they ought to be. That is something that needs to be addressed regardless of what happens nationally with healthcare reform. So there is no way to discuss reform without discussing how to fix that

We need to be working in our state legislature now so that those providers (or the mechanisms to find those providers) are in place, allowing Virginia to be one of the few states ready for this new reality. Because, while the funding and organization has to come from the federal level, the majority of the preparatory work has to be done at the state level; that’s where the primary power for legislating and licensing arises.

Which is where community paramedicine comes in.

COMMUNITY PARAMEDICINE

What do we need to do to fix this? Well, there are a number of things we need to do- but one of the things we can do right now is to pass laws that enshrine community paramedicine as a care modality in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It’s something that we need to do regardless of what happens in Washington, so we can better serve communities from Virginia Beach to Winchester, and Alexandria to Bristol.

What do we need to do to fix this? Well, there are a number of things we need to do- but one of the things we can do right now is to pass laws that enshrine community paramedicine as a care modality in the Commonwealth of Virginia. It’s something that we need to do regardless of what happens in Washington, so we can better serve communities from Virginia Beach to Winchester, and Alexandria to Bristol.

Right now, in Virginia, things generally work like this:

You’re having a medical emergency, or some sort of incident that compels you to call 9-1-1 and summon an ambulance. This may end up being your local county or city fire and rescue department. It may be local volunteer EMTs from the local volunteer EMS group. It may be a private service that’s employed by your locality to provide medical services. Aside from a few dynamics at play – for instance, while a majority of Virginia volunteer EMS agencies attempt to bill for services, they rarely pursue those costs if a patient cannot pay – these agencies are only able to even seek reimbursement for a call if they take somebody all the way to the emergency department.

But let’s say you called 9-1-1, an EMS crew shows up, and it turns out you don’t need to go to the ER for whatever reason. If that’s indeed the case… they don’t get paid. They can’t seek reimbursement for doing “nothing.” But that doesn’t mean nothing gets done, or no costs were incurred. Far more often than not, the professionals staffing these units will do what’s right by the patient. So if you just needed something minor and you’re OK now, they’ll just do what they have to do and eat the cost.

There are a couple of problems here. One, clearly, is that we all are actually the ones eating the cost- remember the principle of There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch.

Two, there’s no in-between there; if the patient doesn’t need to go to the emergency department, but does need medical treatment beyond what the EMS crew can offer, there’s really no choice but to take the patient to the ER anyway. If they arrive on scene and the patient has a medical condition that requires them to be seen urgently, but is not life threatening, EMS has no ability to take the patient to somewhere like an urgent care center or the patient’s primary care physician (PCP).

Last, EMS really has no good options for the superusers in our system, who take up an enormous amount of time, money, resources. “Super-users” with complex medical needs make up a small fraction of U.S. patients, but they account for half of the nation’s overall healthcare spending- and Virginia is no different. There was a patient known to a regional Virginia EMS and hospital group that called 9-1-1 three times a week every week for over 30 years (since the year they became eligible for Medicare) for transport to a number of emergency departments. The patient obviously often called for non-acute reasons, but EMS largely lacked the ability to do anything else about it until the local and state office of EMS and local hospitals got together in a working group specifically for that patient’s needs. Thus, there is a strong case to be made for investment in community services and mental health programs alongside this, but that is for another time.

But what if a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease called 9-1-1 because they were having difficulty breathing, and a paramedic could come on site, administer a breathing treatment, and determine if the patient was now well enough to not require emergent transport, helped them set up an appointment with their primary care provider, AND get reimbursed for that interaction?

What if EMS could be reimbursed for transporting that patient to his or her PCP or an urgent care center instead of having to take the patient all the way to the ER?

What if we could make a serious dent in the critically under-supported mental health field, recognizing that there should be no difference between mental and physical health?

What if a patient ended up only having problems with their medications, and a nurse practitioner in a chase car showed up with the ambulance, determined they didn’t need an ER trip today, helped set the patient straight, assisted them with making an appointment with their primary care provider, and then logged the entire interaction into the patient’s electronic health record so that every provider in the patient’s healthcare network could access it?

What if we could help keep aging Virginians in their own homes, instead of forcing them into nursing homes?

What if allowances could be made for someone with chronic medical problems just needing reassurance they were OK- literally just reassurance and medical clearance- and both they and EMS could go on with their day?

Right now- right this very minute!- we have paramedics, advance practice EMTs, and providers like nurse practitioners and physician assistants with the training and scope of practice through their licenses to do just that. They can help provide public health and primary healthcare and preventive services to underserved populations in the community.

And that’s what community paramedicine- and the entire aegis of mobile integrated healthcare- is all about.

Community paramedicine generally focuses on:

- Providing and connecting patients to primary care services.

- Completing post-hospital follow-up care.

- Integration with local public health agencies, home health agencies, health systems, and other providers.

- Providing education and health promotion programs.

- Not duplicating available services in the community.

Paramedics and EMTs in rural communities are trusted and respected for their medical expertise, the emergency care they provide, and are generally welcome in patients’ homes. These professionals are often consulted for healthcare advice by their friends and neighbors. Their skill set can be equally useful to them in addressing unmet needs for primary care services in the community. For example, the technique used to administer an injection in an emergency situation is the same used for routine inoculations

And we can have that right now. All we need is the legislature to back us up.

ALLIES IN ENACTING

Both county medical agencies (such as fire and rescue departments, community health departments, etc.) and healthcare institutions, public and private, are almost universally supportive of community paramedicine programs and willing to invest in making them successful. Healthcare institutions have a huge incentive to participate in and help fund and organize them, because otherwise they have to eat the cost for that unreimbursed emergency department care (or, at the very least, have to pass those costs on to their other patients).

This is in the same vein as every hospital in Virginia (INOVA, UVA, Sentara, Carilion, Centra, etc.) begging the Virginia legislature to pass Medicaid expansion from 2012 to 2017, even going so far to say they would voluntarily pay the Commonwealth’s costs for enacting it in perpetuity if only the legislature would agree to pass the expansion. Hospitals have enormous incentive to not only cooperate with this program, but to help fund and enact it, because (as noted previously) it’s much less expensive for them to help fund community paramedicine initiatives than have to take on the cost of an emergency department visit. We can instead help them focus their emergency department staff on doing what they do best. So there exists a supreme potential for a public/private partnership to make this program work in every corner of the Commonwealth.

SUCCESS ELSEWHERE

Pilot programs across the country have proven that this program works no matter in what sort of area it has been implemented. Localities as different as Birmingham, Boston, and Wake County, North Carolina have all run successful pilot programs for community paramedicine, which shows its potential for rural, urban, and suburban populations.

Here’s a few links for your perusal on those subjects:

The growing guerilla healthcare movement- community paramedicine.

Community paramedics hit the road.

Again, this doesn’t require changing any licensing or training laws. Paramedics, nurse practitioners and physician assistants have the ability to do everything clinically that is required for this program to work right now. It is within what the Commonwealth of Virginia already grants them for scope of practice. It just needs to be formalized, allowing them to seek reimbursement from sources such as Medicaid.

CHALLENGES

Perhaps the biggest challenge, regardless of whether or not we pass legislation in support of community paramedicine, is to make sure we have enough providers available. That means incentives for more EMTs, paramedics, nurses, nurse practitioners, PAs, MDs, etc. We already have a dramatic shortage of providers as it is, so we need to address this anyway; it just has the potential to get much worse without action.

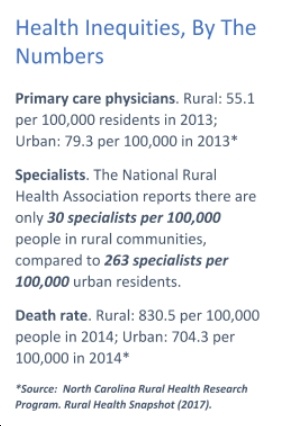

Right now, apropos of nothing, physicians in primary care are retiring at a rate that is utterly irreplaceable. I often tell the story about my kids’ doctor. He not only delivered both of my boys, but 30 years ago, when he was a brand-new family practice doc, he also delivered my wife. He has something just short of 10,000 patients in the Free Union, Virginia area. When he retires, which will be soon, who’s going to replace him?

Right now, the honest answer is probably: nobody. And so those patients will have to try and seek care with another physician; some may have to drive all the way to Charlottesville to do that. There are parts of Free Union where it’s easily a 45-minute drive minimum, one way to Charlottesville.

What that means is that people are much more likely to let care go unsought, which obviously is not a solution. Putting things off and ignoring them ends up costing more in the end when you have to be rushed to the emergency department. Which gets us back to where we started with inefficient care provision that we ALL end up paying more for, but most pertinently, is far worse for the patient.

SO WHAT DO WE NEED TO DO LEGISLATIVELY?

So, the big question is, what sort of legislation can you advocate for to go into making this work?

Here’s a list of some potential legislative solutions you can discuss doing when we talk about making community paramedicine work:

– Give county fire and rescue departments the legislative clearance to run these programs, and work to set up private/public partnerships among them and local healthcare systems to make it work.

– Allow Virginia Medicaid to reimburse community paramedicine initiatives.

– Empower/fund efforts for Virginia public colleges to significantly increase enrollment in medical provider programs (i.e., EMT, Paramedic, RN/BSN, NP, PA, etc.).

– Empower the Office of Emergency Medical Services to work with both public and private agencies to make these programs work for every community in Virginia.

– Carve an exception in the Dillon Rule for county fire and rescue departments empowering them to help find a local solution to local problems. An example of this was Albemarle County Fire and Rescue’s attempt to push a .5% increase in sales tax on cigarettes, which they calculated would pay for all of their training and equipment, later blocked by the General Assembly (and Altria-backed politicians).

– Exempt from state income taxes critically-needed medical professionals (like dentists, psychiatrists, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, etc.) who agree to live and work in “medical deserts” (rural/underserved locales) .

– Provide tax credits for employers who hire/retain volunteer emergency services personnel, including tax credits for giving paid time off, with special benefits to those (especially small businesses) who do so in medical deserts.

– Give fiscally-strapped Virginia counties a credit to send county citizen providers (emergency services and healthcare related) to a Virginia school for free training if they’ll agree to work/volunteer for a certain period of time.

– Shorten the amount of time required for nurse practitioner autonomous practice from the most onerous in the country (currently at 10,000 hours) to standards in-line with those of the U.S. Military and Department of Health and Human Services.

– Make it easier, not harder, for you to find a job helping people in the Commonwealth of Virginia if you’re a returning U.S. Army medic, U.S. Navy corpsman, or have held another equivalent position in the U.S. military. We need to team up with the Board of Health Professions and learning institutions in the Commonwealth to build programs specifically tailored for returning veterans to turn their already extensive training into a degree to become a medical professional. And if they go to a medically underserved part of the Commonwealth to practice? Then the Commonwealth should stand up for the men and women who’ve stood up for us and pick up the tab.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Healthcare is an issue that touches every single Virginian- we will all access the healthcare system at some point in time- and community paramedicine is a great way to help provide that access for all Virginians in a comprehensive, high-quality, cost-effective way. If we want to prove that we’re speaking to the kitchen table issues of working Virginia families, fighting for community paramedicine is a great way to do just that, while simultaneously preparing our state for the challenges on the very near horizon.