From the Commonwealth Institute for Fiscal Analysis:

High housing costs and income inequality meant even before the pandemic many families in Virginia did not have the means to build up savings that could have cushioned the impact of the pandemic on families and the economy even as incomes grew slightly for middle-income households and the number of very high-income households grew in 2019 before the pandemic began, according to data from the U.S. Census American Community Survey that was released today.

Between 2018 and 2019, Virginia’s poverty rate fell 0.8 percentage points and median household income rose by 3.4% after adjusting for inflation. Housing costs remained high – a trend that contributed to this year’s severe health and housing needs.

The pandemic has devastated the economy, and people across the country are struggling to get by. Federal and state policymakers must act now or they will leave millions of families to face this crisis on their own. This includes federal aid that matches the extraordinary need that households and our economy face and state support for health care services, economic supports, hazard pay and personal protective equipment (PPE) for front-line workers, and helping schools respond to the pandemic.

The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on people across Virginia – particularly families of color and those with low incomes – make the need for bold action at the state and federal levels clearer than ever. The Census Household Pulse Survey has more up-to-date data than the American Community Survey, allowing a look at the impact of the pandemic and recession.

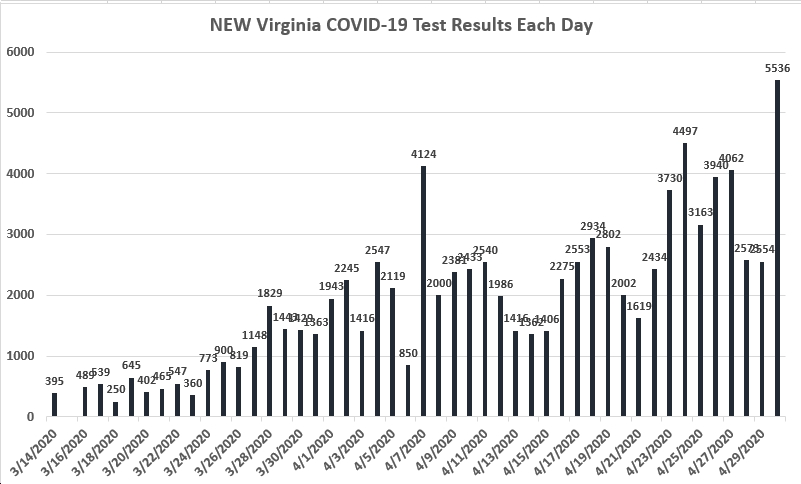

- 10% of adults reported that their household sometimes or often didn’t have enough to eat in the last seven days

- 18% of adults in households with children reported that their kids sometimes or often didn’t eat enough in the last seven days because they couldn’t afford it

- 19% of adults who live in rental housing reported that they were behind on rent

- And 24% of all children in Virginia live in a household that is either not getting enough to eat or behind on housing payments.

This hardship is being felt more acutely by people of color in Virginia who were already facing barriers before the pandemic and may be less likely to have jobs that can be done from home. More than 1 out of every 8 working people in Virginia who identify as Black, Latinx, or Asian American and Pacific Islander were unemployed this summer and actively looking for a job or were on temporary layoff without pay, compared to 1 out of every 19 working people who identify as non-Hispanic white. For Black people in Virginia, who are too often the “first fired” during a recession, a lack of jobs is compounded by challenges for Black business owners.

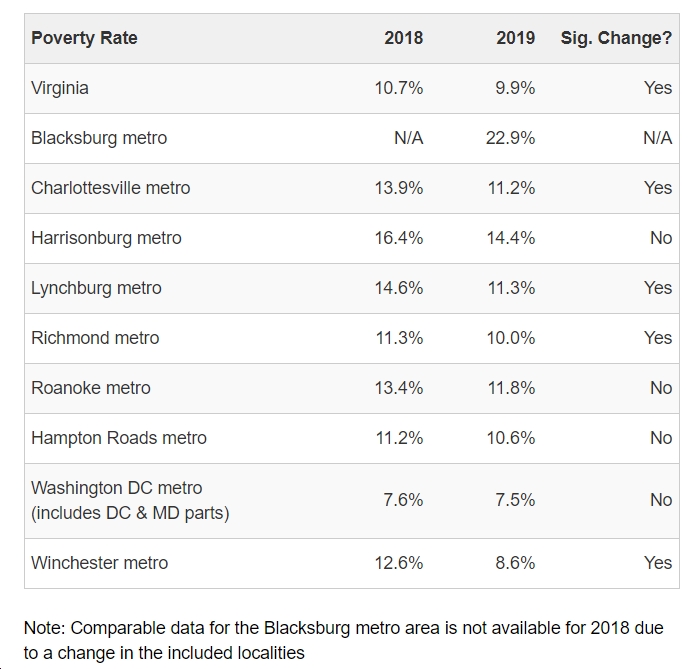

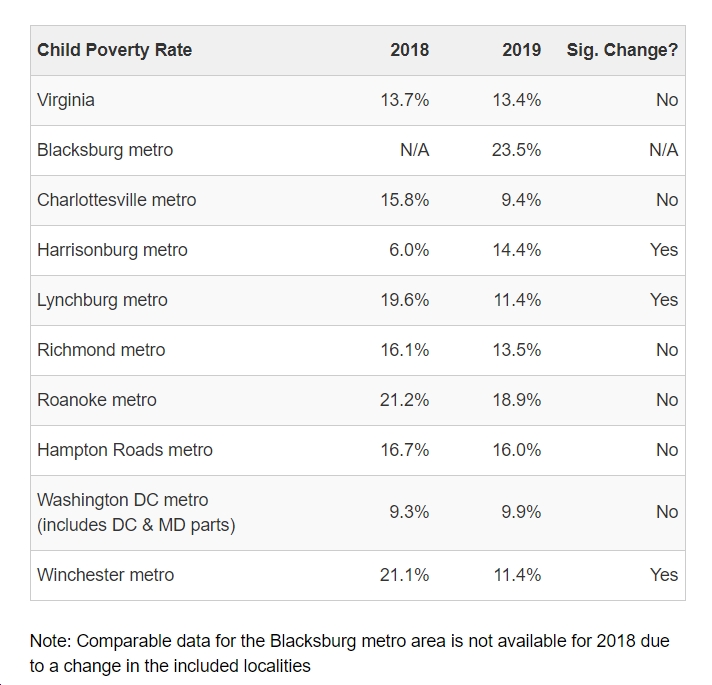

Digging deeper into the 2019 data that shows conditions in Virginia going into the pandemic, the statewide poverty rate was 9.9%, down slightly from 2018. The share of Virginia children who are living in households with incomes below the poverty threshold was 13.4% in 2019, indicating that even after 10 years of economic recovery, many Virginia families with children were still struggling to make ends meet. Even as the share of Virginia households with incomes above $200,000 continues to grow, 1 in 3 households in Virginia still have incomes under $50,000 a year. Too many backwards choices by policymakers over the years contributed to many working people in Virginia being left behind, while the next generation of Virginians attend schools that have endured a decade of cuts.

Two-thirds of Virginia families with incomes below the poverty threshold in 2019 had at least one adult in the household who is working. As a result, there were around 251,000 working adults living in Virginia households with incomes below the poverty threshold, which was just $25,926 for a married couple with two children. And Virginians who are Black or Latinx continue to be more likely than white and Asian American Virginians to have incomes below the poverty line.

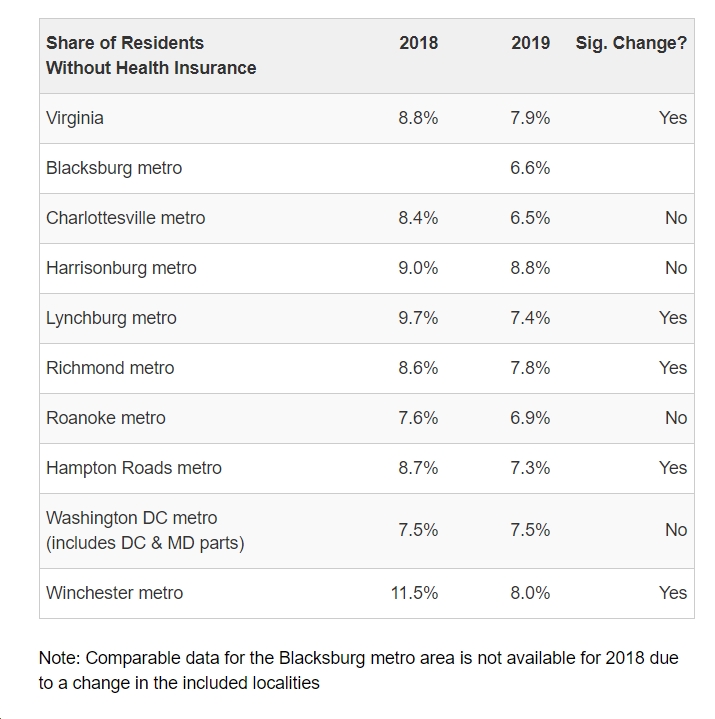

Significantly, the 2019 data show one major improvement in Virginia — an increase in the share of Virginians who have health insurance. This increase was the result of policymakers expanding access to Medicaid during the 2018 legislative session, a change that was implemented on January 1, 2019. Virginia was the only state in the country to have a significant decrease in the share of residents who are uninsured from 2018 to 2019. This improvement can fairly be attributed to the expansion of Medicaid and the work of thousands of advocates across the state to push for this policy. Tuesday’s press release includes more discussion on this health insurance data as well as ways that policymakers can build on this momentum to improve access to affordable and quality coverage for even more Virginians. More recent policy improvements such as raising Virginia’s minimum wage have not yet been implemented and therefore do not impact the 2019 data.

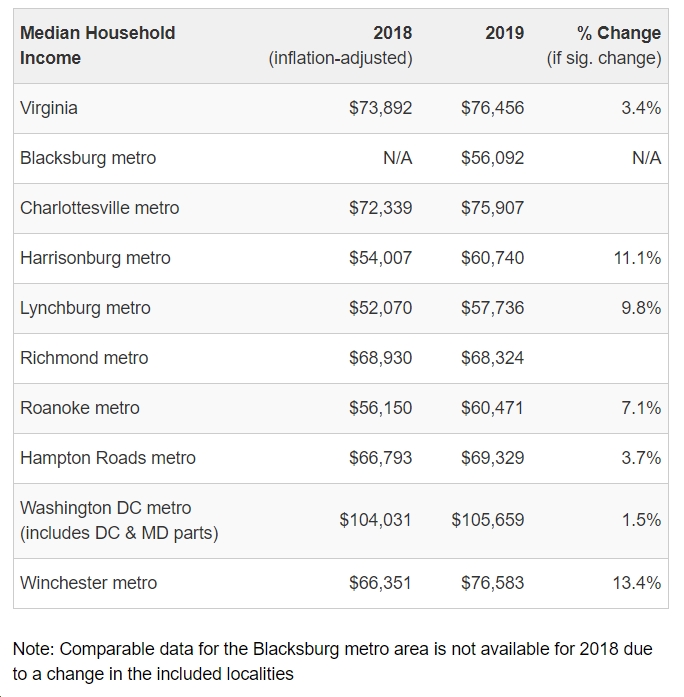

There are significant differences in opportunity both across and within regions. Many parts of Virginia experience far lower typical household incomes than the statewide levels. The metro areas of Blacksburg, Harrisonburg, Lynchburg, and Roanoke all have median household incomes at least $15,000 below the statewide median of $76,456; the Richmond and Hampton Roads areas also have median household incomes below statewide levels, although less dramatically. Additional tables with income, poverty, and health insurance rates by region can be found by clicking through to TCI’s blog.

The good news is that federal and state policymakers can respond to the health and economic crisis created by COVID-19 in ways that rebuild the economy for a more equitable future.

Federal policymakers must act swiftly to provide more federal aid that matches the extraordinary need that households and our economy face. That includes boosting vital assistance programs such as SNAP (formerly known as food stamps) and housing assistance, extending enhanced federal unemployment benefits, and allocating additional aid to states and local governments that can help prevent further layoffs and cuts to core public services.

State policymakers must act now — during the current legislative session — to meet the demands of the moment by advancing bold, anti-racist policies to build equitable and inclusive communities and an economic recovery that extends to all people. This should include using all available resources to meet the needs of families and communities, reinvesting in health care to remove barriers for immigrant communities and new mothers, providing hazard pay and PPE for front-line workers, and helping K-12 schools respond to the pandemic rather than repeating the mistakes of the last recession that reduced support for schools serving low-income families, resulting in a long-term lack of resources.

The challenges, improvements, and inequities shown in the 2019 data are not due to chance; they are the result of the policy choices that were made up until that point. With the current pandemic showing the destabilizing consequences of an economy where many people — particularly communities of color and low-income families — face barriers to advancement and saving while other people just grow richer, state and federal policymakers have the choice to help families get through the current crisis while rebuilding for a better, more equitable future. Let’s make that choice.

— Laura Goren, Research Director

Click here to see tables with income, poverty, and health insurance rates by region on TCI’s blog.