by John F. Seymour, a long-time resident of Arlington, Virginia

by John F. Seymour, a long-time resident of Arlington, Virginia

Sometimes, when I need to feel seven years old again, training wheels off, red streamers fluttering from the handle grips, a playing card in the spokes, I ride the Arlington bike trails. And I’m not alone. Arlington’s 50 miles of bike trails are among the county’s most popular recreational amenities. Separated from street and highway traffic, the trails are safe, handsomely landscaped, well-maintained, and easily accessible for nearly every resident. Arlington’s recently approved Bicycle Element to its Transportation Management Plan documented very high levels of citizen participation in recreational cycling, particularly the county’s bike trails, with more than 90% of survey respondents expressing a wish to cycle more often. Arlington’s amended Public Spaces Master Plan similarly found that cycling the bike trails was among the county’s most enjoyed recreation activity.

The popularity of cycling in Arlington might seem to some, perhaps, a bit curious. Of Arlington’s 26 square miles, only about 11% is devoted to parks and green space. Despite the county’s small area, high density, and increasing urbanity, however, local government leaders have invested heavily in recent years to expand and improve the area’s bike trails. The League of American Bicyclists awarded Arlington a rare Silver Rating as a Bicycle-Friendly City and Bicycling Magazine included Arlington among its Top 20 Best American Bicycling Cities. Other accolades, including Arlington’s selection as the “Fittest City in the Country” by the American College of Sports Medicine, and “Best City to Live In” and “Best City for Millennials” by various lifestyle publications, frequently reference the quality of Arlington’s parks and bike trails.

It is true, of course, that cycling also ticks some of the virtue-signally boxes for which Arlingtonians are both praised and caricatured. It is a healthy, low-impact exercise that can be enjoyed for a life-time. (The University of Washington’s Population Health Institute rankings for 2020 ranked Arlington the second healthiest of Virginia’s Counties and Cities (Fairfax was ranked first)). It is a sustainable form of transportation, carbon free, and reduces the county’s environmental footprint. It is inexpensive, free from both licensing requirements or costly equipment, and promotes equity. It is also community-centered, consistent with the county’s emphasis in promoting an active civic life and public engagement. Every day, the trails are filled with families and members of biking clubs, sharing the trail with other cycling enthusiasts.

Cycling’s relatively slow and deliberative pace also helps to harden the glue in civic life by encouraging us to see our neighborhoods up close. It enables a better and more accurate understanding of our “place” and the people in it. Cyclists can’t avoid noticing Arlington’s rapid development, surging skyline, and increasing cultural and ethnic diversity. At the same time, cycling exposes some of the cracks and strains in Arlington as the county adjusts to change, or struggles to — gentrification, soaring property values, tract mansions replacing modest 1950-era ranch homes, shrinking tree canopy, flooding aggravated by an over-taxed stormwater system. And everywhere, it seems, is evidence of Virginia’s and Arlington’s fraught racial history — history that can no longer be ignored or explained away as simply “the way it was.” But equally visible are signs that those who have been ignored or maligned by history are now insisting on revisions, or wholesale re-writes of their own.

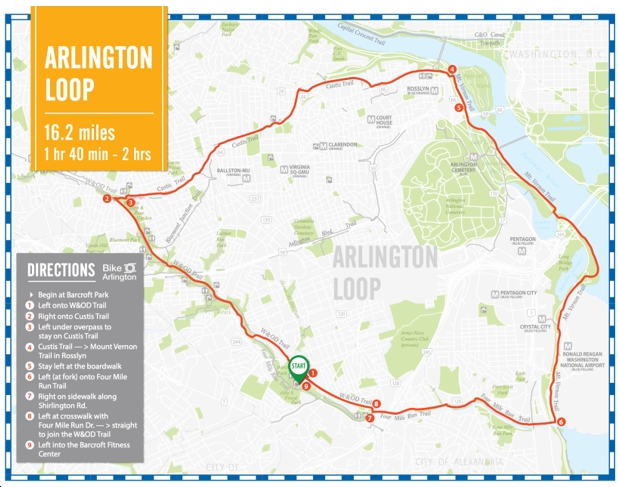

All of Arlington’s trails encourage a greater kinship with one’s neighbors as well as a deeper understanding of where Arlington came from and where it is headed. My favorite, though, is the Arlington Loop — a 16-mile circle of attractive and smooth riding that circumnavigates the county. Earlier this year, local cyclists were asked by county staff to chose the “best” bike trails. The four top choices (the Washington and Old Dominion (W&OD) Trail, the Four Mile Run Trail, the Mt. Vernon Trail, and the Martha Custis Trail) make up the entirety of the Arlington Loop. Completed in the late 1990s, the Loop follows Arlington’s two major natural waterways — Four Mile Run and the Potomac River — as well as one man-made feature, Interstate 66. It bisects or abuts many of Arlington’s neighborhoods and most county residents live within a mile or two of the Loop.

The trails making up the Loop are managed by three different jurisdictions — Arlington County, NOVA Parks, and the National Park Service. To the cyclist, though, the Loop seems integral and seamless. It runs generally (if you bike it, as I do, counterclockwise ) from north-western Arlington along Four Mile Run to the Potomac River. It then follows the River to Rosslyn and rises along Route 66 to return near Falls Church. On average, the Loop takes about two hours to complete, depending on whether a cyclist takes side trips to enjoy local parks, neighborhoods, national monuments, or other sights.

W&OD Trail

The W&OD Trail in Arlington is part of the W&OD Railroad Regional Park, administered by NOVA Parks. Together with the Four Mile Run Trail, it winds through more than 580 ares of woodlands and meadows, past a necklace of small jewel-like parks such as Benjamin Banneker, Madison Manor, Bon-Air (with its masses of roses in bloom in June), Bluemont Park, Gencarlyn Park, Barcroft Park, and Shirlington and Jennie Dean Parks, finally reaching the Mt. Vernon Trail near National Airport. It was one of the first recipients of the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy’s Hall of Fame awards, granted to recognize exemplary trail systems with remarkable scenic value, trail amenities, and historical significance.

Like many cyclists in north Arlington, I connect with the Loop by first riding to the W&OD Trail in the East Falls Church neighborhood of North Arlington. Other routes are more direct, but I have become, in a matter of weeks, an avid admirer of the new $6 million curved cycling bridge constructed above Lee Highway (recently renamed Langston Boulevard). The 600-foot bridge is stunning as a piece of architecture and shines as an outstanding feature of the local cycling network. To one raised in a rural and poor community where biking was conducted entirely “at one’s own risk,” the new bridge stands as a testament to the region’s support of biking as part of a genuine multi-modal transportation system. In my home town, the biking infrastructure consisted entirely of the air hose at the Sunoco Station and, depending on the ride, maybe a portion of asphalt shoulder instead of gravel or cinders. The new W&OD bridge is a revelation — smooth, broad, and well lighted. It also remedies one of the few remaining major bike trail hazards — the bottleneck as the W&OD Trail crosses busy Langston Boulevard near the ramps for I-66 and Washington Boulevard.

A short distance down the W&OD Trail lies one of the last remaining cornerstones of the original District of Columbia boundaries, erected before the recession of the Virginia portion back to Virginia. Located adjacent to the newly-renovated and expanded Benjamin Banneker Park, a nearby plaque honors the free African-American and self-taught mathematician and surveyor who helped map the boundaries of the new District. Although not intending to, the brief biography on the plaque might be read to deracinate Banneker. Contemporary historians admire Banneker for his extensive correspondence with then-Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson when he pointed out (as Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth and others did later) the hypocrisy lying at the heart of Jefferson’s idea of liberty — that whatever noble sentiments Jefferson may have expressed in his writings on liberty, he was a slave owner and thus “detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren under grinding captivity and cruel oppression.”

In a return to the present day, and a bit farther down the Trail, cyclists occasionally encounter more ephemeral and less eloquent political commentaries. Although the bike trails are only rarely defaced by graffiti, cyclists might now find their ride interrupted by “Trump Won” signs spray-painted on the huge Virginia Power electric transmission lines. In a county where only 17% of the residents cast votes for former President Trump (the smallest percentage of any Virginia county), the graffiti stand as a warning that, even on Arlington’s bucolic bike trails and in a county with a proud tradition of tolerance, mutual respect, and civility, today’s climate of toxic political divisiveness and viral falsehoods cannot be avoided entirely.

Below Benjamin Banneker Park is a string of other small, well-maintained wooded parks, many with rest areas, water stations, bathrooms, shelters and other conveniences. Arlington is regularly and properly praised for the excellence of its park system. The Trust for Public Land has, for years, rated Arlington’s parks among the very best in the nation. Although the Park system has its crown jewels — particularly the spectacular new Lubber Run Community Center and Long Bridge Aquatic Center — its everyday treasures are the little leafy oases along the the stream where children play and explore the shallows for frogs, salamanders and minnows. Sparrow Pond, in particular, is worth a brief stop. With an overlook on the Trail, the Pond was designed to manage stormwater and is now inhabited by a family of beavers. Very cute, to be sure when glimpsed at twilight, but wholly uninterested in stormwater management. The beavers have quickly denuded much of the hillsides to build their lodge and dam, and as a food source.

Four Mile Run Trail

The Four Mile Run Trail segment of the Loop is relatively short (only 3 miles), beginning in Shirlington and ending at the junction of the Mount Vernon Trail at National Airport. Near the Shirlington neighborhood, where the W&OD Trail joins the Four Mile Run Trail, the Loop passes by one of Arlington’s historic African American neighborhoods, Green Valley. Green Valley was originally settled by some of George Washington’s former slaves and populated further during the Civil War with fugitive slaves emancipated by advancing Union troops. Named “Nauck” after a former Confederate soldier and prominent landowner, neighborhood residents recently petitioned Arlington County to change the name to Green Valley, arguing that the current name improperly honored a Confederate soldier who, according to historians, contributed little to the betterment of the community.

Like Arlington’s other predominantly minority neighborhoods today, Green Valley was the victim of red-lining by banks and other lenders (withholding mortgage capital from African American borrowers while favoring white homeowners) and even today holds the county’s highest concentration of poverty. Unlike Arlington as a whole, the neighborhood’s residents are overwhelmingly renters and median home values are less than half that of other neighborhoods adjacent to the Loop. And while most of Arlington’s public schools have relatively few students who qualify for free or reduced price lunches, the elementary school serving Green Valley — Charles Drew Elementary— reports that more than 60% of its students qualify.

My trip began a few steps from Tuckahoe Elementary School in the northern part of the county where less then 2% of students qualify for free or reduced lunches. Unsurprisingly, Arlington’s periodic surveys of citizens’ health outcomes consistently report a 10-year difference in life expectancy between those living in neighborhoods in north Arlington and residents of predominantly Africa-American neighborhoods like Green Valley.

The principal neighborhood park serving Green Valley, Jeannie Dean Park, abuts the Loop and was one of the rare public parks created in Jim Crow Virginia for an African-American community. Aging and with few amenities, the Park is currently undergoing a major renovation. The renovated and enlarged Park, together with other park initiatives in South Arlington, will help to correct what the Trust for Public Land and other organizations have seen as the single most serious deficiency in Arlington’s park system — insufficient equity in its allocation of resources. Arlington’s relatively poor score on the Trust’s metric for “equity” derived from a finding that neighborhoods of color in Arlington are allocated 27% less park space per person than the county median and 34% less space than white neighborhoods.

As the Trail continues into South Arlington, it passes the county’s sprawling Water Pollution Control Plant, which treats more than 23 million gallons of wastewater daily and discharges treated water to Four Mile Run. Concerned about the vulnerability of the Plant to flooding and evidence of increased instability and erosion on the banks of the stream, the county recently completed an extensive restoration project (the winner of the Governor’s Environmental Excellence Award) along the stream banks. The project improved stormwater control along the watercourse by transforming acres of rip rapped embankments into a living shoreline, with thousands of native plants, luminous when backlit. With even the slightest breeze, the native grasses and other tall perennials capture that frustratingly rare yet essential element of designed landscapes — motion.

Near its eastern terminus, the trail passes beneath the former Jefferson Davis Highway (now Richmond Highway). For years, Arlington County had sought legislative authority to rename the portion of Jefferson Davis Highway that lay within the county, but was opposed by Republican lawmakers controlling the Statehouse in Richmond. In 2019, Arlington was finally able to rename the portion of the highway lying within the county. Following the 2020 election and the statewide election of Democrats in the Assembly and Senate, legislators finally agreed to rename all remaining portions of the Highway as “Emancipation Highway,” effective January 1, 2022. That change represented, belatedly to many Arlingtonians, an important correction to local history and collective memory. Instead of a road dedicated to a secessionist who waged war to preserve white supremacy and the enslavement of millions, the road will soon honor the emancipation of those slaves.

Mount Vernon Trail

Managed by the National Park Service, the Mount Vernon Trail parallels the George Washington Parkway and hugs the western bank of the Potomac River. For nearly all its length in Arlington, the Trail provides open and uninterrupted views of the River and the iconic monuments in the District of Columbia.

A very short distance from the Mount Vernon Trail, using an intersecting bike trail, lies Arlington National Cemetery — 264 acres of rolling, wooded landscape gracing the Potomac. The view from Arlington House, at the top of the Cemetery, provides one of Virginia’s finest views of the National Mall. Many visitors find it restful and centering, a balm to the wounds of contemporary political partisanship and tribalism. During a period where everyone seems to be choosing their own reality, the authenticity of sacrifice there cannot be denied. Arlington Cemetery is not our nation’s history recorded on vellum, or parchment, or inscribed on marble, nor does it celebrate the hyper-nationalism of the post-9-11 era. It is the old patriotism that flows from courage and loss and is displayed, amidst a landscape that strains the very definition of poignancy, in neat rows of modest headstones.

But the portrayal of our national story here, too, is in evolving. Like Arlington’s renaming of the Washington & Lee High School, Jefferson Davis Highway, Lee Highway, and the Nauck neighborhood, Arlington is replacing its own logo, currently a stylized version of the Arlington House, with something more praiseworthy than the front portico of a southern plantation built and tended by slaves. As a totem, Arlington House no longer reflects Arlington’s idea of itself, if it ever did.

Despite their beauty, other elements of the Cemetery also remain problematic. The Cemetery’s Confederate Memorial, commissioned by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and dedicated to “Our Proud Heroes,” stands in the far western corner of the Cemetery. It is topped by a classical female figure, representing “the South,” her eyes looking South. It strives for an elegiac air, but traffics in the timeworn orthodoxy of the Lost Cause, reinforcing the myth that the South fought nobly, not to preserve slavery (the South’s much maligned and benevolent institution), but states’ rights. Depicting the “kindly relations” that existed between master and slave in the South, two of the figures on the frieze below the statue are portrayed as African-Americans. One is a young male slave, faithfully following his young white officer and owner to war. The second is a depicted as a elderly female slave, a “Mammy,” weeping and holding the child of a white Confederate officer who is also going off to war.

The monument may remind many observers that, in some ways, national and racial reconciliation remain as distant as ever. The graves of the U.S. Colored Troops at Arlington Cemetery (38,000 lost their lives during the Civil War, with a mortality rate higher than white troops) are set well apart from their white comrades, segregated even in death. It was not until July 26, 1948 — five days before my own birth — that segregation of burials ceased and President Truman issued an Executive Order integrating the armed forces.

The Martha Custis Trail

The final leg of the Loop, the Martha Custis Trail, is a hilly 4.5-mile stretch of narrow asphalt paralleling Route 66. The ride back up to the Fall Line is not as pleasant as the ride down, nor is it as scenic. Although the bike trail remains well-maintained, separate and safe, it is hemmed in by the tall grey steel structure of the Route 66 sound barrier. Unlike the other parts of the Loop, the Custis Trail did not result from careful federal, state or county planning. Rather, it was constructed, in large part, to resolve more than 10 years of passionate yet ultimately unsuccessful opposition to the highway’s construction. When the Department of Transportation planned the new commuter road, it had absolutely no interest in building a bike trail. Facing hostility from homeowners living near the Route 66 corridor and continued pressure from environmentalists, the agency reluctantly amended its plan to include the bike trail and sound barrier.

As the Mount Vernon Trail merges with the Martha Custis Trail, the tall office buildings of Rosslyn form an imposing skyline and loom over the Loop. Rosslyn hosts some of the nation’s most powerful corporations and most exclusive and expensive condominiums. In their shadows, however, and clinging to the edge of the Trail, is one of the county’s most stubborn collection of homeless. Although Arlington has made great strides in reducing its homelessness population in recent years, the pandemic’s economic impact and the exponential increase in housing costs in Arlington, have set back its efforts.

The final ride up the Custis Trail provides further evidence of persistent inequality and a growing housing divide in Arlington. Although the sound barrier muffles the sounds of traffic on Interstate 66, some riders might be forgiven for sensing that the wooded side of the trail, marked with colorful decorative signs identifying many of Arlington’s sheltered single-family neighborhoods, is walled off to them by other barriers — those of class and privilege. Median home prices for many of the neighborhoods in the northern half of Arlington now exceed $1 million. They are unattainable by the legions of Arlington’s teachers, firemen, police, bus drivers, and nurses, and beyond the imagination of the county’s health aids, housekeeping and personal care workers. The thousands of new workers at Amazon and sister companies expected to arrive within the next decade will compete for housing in an already strained market.

Back Again

Like many users, I imagine, I cycle the bike trails principally because they are a joy to ride — safe from traffic, filled with nature, and humming with pedestrians and fellow cyclists. And they also remind me how fortunate I am to live in Arlington, a community whose robust receipts from homeowners and businesses taxes can fund both core services and charming niceties, like bike trails.

But as I cycle around the Loop, I am forced to acknowledge that my experience is not that of everyone and that, despite its progressive politics, achieving the broad goals in the county’s Equity Resolution, will take much more than changing street names, removing memorials, and redesigning logos. It will take a clear-eyed and steadfast willingness to examine our county up close, both our diverse neighborhoods and our troubled history, and work together, as a community, to increase awareness of how far we have to go. The bike trails will help, I think, to take us there.