VPAP is out with its annual legislators’ “batting averages,” as you can see in the following screenshots. But first, see here for all the usual caveats:

- These numbers can be *highly* misleading if you look at them the wrong way, or as in the case of VPAP, they can be misleading if you fail to present the numbers with explanation, important context, etc. as VPAP indeed fails to do.

- Also, as Cindy Cunningham explained back in 2019, “There are many, many ways that a legislator might end up with a low ‘batting average’ on the VPAP scorecard. The legislator might, in fact, put in lots of ill-conceived bills–ideas that haven’t really been thought through very well, poorly designed plays.”

- Or, “a legislator might also end up with a low score by putting in lots of controversial or partisan bills.”

- “On the flip side, a sure way to get a high score is to put in a lot of relatively sleepy little bills–clean up some badly-worded or vague section of the code, solve some minor local problem, be the patron of one of the many, many bills that are voted through unanimously – ‘in the uncontested block.’”

- “Lastly, a legislator may get a high score for having a good sense of what can or cannot pass, for working hard with stakeholders and other legislators before and during the process to tweak the language so that it will have as little opposition as possible, for being willing to amend on the fly as needed. Think of this as playing good, smart, fundamentally sound baseball.”

- “But just like a win-loss record is a poor measure of how your pitcher did, and how ‘advanced sabermetrics’ are far more revealing, this VPAP ‘batting average’ is a poor metric for how our legislators did.”

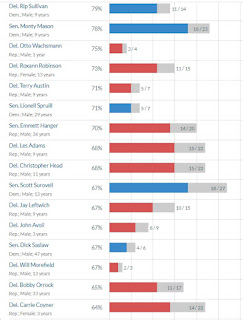

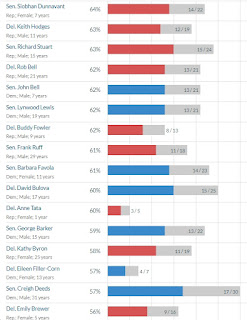

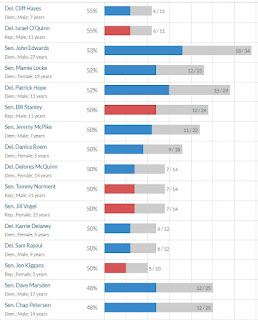

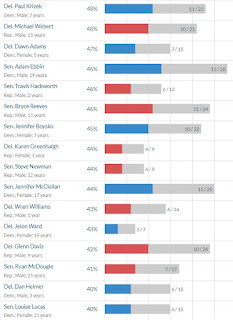

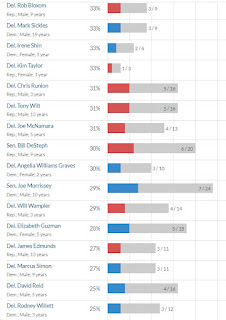

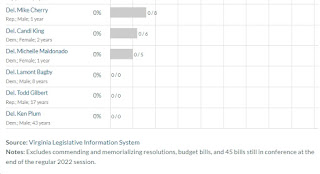

- Also worth looking at, along with the % of patroned bills passed, is how many bills each legislator put in, and how many total bills passed. Thus, clearly having a 100% batting average is not nearly the same thing if you patroned one or two bills that passed versus, let’s say, 40-50 bills, of which perhaps half or two-thirds passed. And again, one really needs to look at how complex, “significant,” etc. each bill is, as well as how much time/effort was required of the patron to get it passed, how much help they had in doing so, etc.

- Finally, it’s important to keep in mind that different members of the General Assembly have different roles. Thus, someone in leadership might spend a big chunk of their time…well, leading! As opposed, that is, to worrying as much about their own bills. Or maybe they try to do both. But regardless, the point is, again we’re somewhat comparing apples/oranges/bananas here.

- With all those caveats, there’s an argument that, perhaps, “batting averages” and statistics like the following aren’t even worth presenting. Or maybe they’re worse than nothing, as they could be misleading? I’d argue that, yes, that’s all true, if you just take the “batting averages” alone, and don’t do some serious “advanced sabermetrics,” as Cindy notes. In short, I’d use the following numbers to *start* a conversation, most definitely not to *end* it. With that…here are the numbers, with a few things that jumped out at me (above each graphic)…

Overall, in the 2022 General Assembly, 40% of introduced bills ended up passing – down from 57% last year and 45% in 2020. By party, Republicans passed 42% of their introduced bills, while Democrats passed 39%. Men passed 43% of their introduced bills, while women passed 35% of theirs. And those with the most seniority (16+ years) passed a whopping 52% of their introduced bills, while those with just 0-4 years in office passed just 26% (!) of their introduced bills (*huge* difference there). Finally, note the contrast from last year, when Democrats had a “trifecta” (control of the House of Delegates, State Senate and governorship), and when the highest legislative batting averages skewed heavily “blue,” with the lowest – including Amanda Chase, Kirk Cox, Glenn Davis, etc. at zero – skewing heavily “red.” This time around, with divided government, it’s more of a mixed bag…