( – promoted by lowkell)

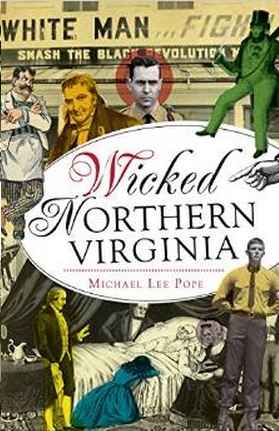

The photos and political cartoons in the cover’s collage and interspersed throughout the book’s 131 pages in Wicked Northern Virginia caught my attention. I was intrigued and spooked by some of the photo subjects: portraits, paintings, grave-markers, and “wicked” places of time gone-by, such as a bordello houseboat, a tobacco barn, and turn of the 20th century barrooms. In one photo, five men sit or stand on the steps of a house porch under a banner bearing slogans of the American Nazi Party; the house that once served as headquarters was on a street near where I live now. In another, a row of low-slung buildings and telegraph poles line a dirt road in a place I didn’t recognize called “Hells Bottom.”

The photos and political cartoons in the cover’s collage and interspersed throughout the book’s 131 pages in Wicked Northern Virginia caught my attention. I was intrigued and spooked by some of the photo subjects: portraits, paintings, grave-markers, and “wicked” places of time gone-by, such as a bordello houseboat, a tobacco barn, and turn of the 20th century barrooms. In one photo, five men sit or stand on the steps of a house porch under a banner bearing slogans of the American Nazi Party; the house that once served as headquarters was on a street near where I live now. In another, a row of low-slung buildings and telegraph poles line a dirt road in a place I didn’t recognize called “Hells Bottom.”

Thus primed, I started chapter one, and found the book hard to put down. Morbidly engrossed in the death scene of a stoic George Washington, I felt the horror of modern hindsight as I read of the extent of bloodletting used by the doctors at Mount Vernon in their well-meaning attempts to save him. Only one of the three doctors knew enough of the latest medical practices to even question repeating the treatment.

Pope begins his book with a promise to divulge events buried in Northern Virginia’s history, events that are wicked because they involve “murder, mayhem, sex, violence and politics.” Each chapter details a different episode, and the first chapter turned out to be one of my favorites, even though I thought it marginally wicked, compared with the activities of other chapters. Each chapter also has a unique voice conveying a flavor of the language of the times. I imagine this could be a natural outcome of the research for the book, which references court proceedings, quotes Colonial Council minutes, and includes excerpts from the accounts of old newspapers and gazettes. The Bibliography includes collections of stories, historic narrative accounts, and an 1894 volume by Teddy Roosevelt, The Winning of the West. All of these sources would be written in the vernacular of the time. In fact, on an Acknowledgements page, Pope thanks Julie Downie for “helping me translate Victorian euphemisms.” Even with these hints of unfamiliar, old-fashioned turns of phrase, the narrative flows, helped along by Pope’s use of dialog. My favorite chapters are based on my personal interests and preferences for topics and patterns of speech.

The book can be read straight through or by skipping, aided by informative chapter titles. I sometimes privately bemoan the currently common practice of entitling books with the “Title: After-Colon-Insert-Elevator-Speech” formulation, for want of the opportunity to treat a title like a morsel of poetry. But these chapter headings gave me my desired morsel, while also telling me the locale and form of wickedness, and hinting at the time period when I recognized a historic name.

The chapter with the title beginning “Nine Pints” describes the medical practice of bloodletting that likely hastened George Washington’s death. “Halfpenny Hitler” chronicles the rise and fall of a Nazi organization once headquartered in Arlington, complete with bizarre, dramatic plot twists. “Chaff Before a Whirlwind: Arsenic and Old Lace in Leesburg” follows court proceedings in a 19th century murder mystery in which a suspicious number of family members (save the defendant) dropped dead of arsenic poisoning. The state of scientific knowledge at that time for assessing poisoning by arsenic might horrify anyone who’s watched a TV episode of CSIS. “First Contact: Murder and Mayhem in the New World” describes more complicated scenarios and sets of relationships than the oversimplified version I learned in primary and secondary school classes. “Tobacco Insurrection” describes shenanigans in Prince William County when Britain instituted inspections of tobacco barrels to prevent being cheated by colonists. “Supervisors for Sale” describes a Fairfax County zoning scandal during a 1960’s real estate boom, and reveals a surprisingly low payout received by the officials guilty of granting zoning favors. “Fire and Brimstone” tells of tensions among residents (both pro-Confederacy and pro-Union) and the Union army that occupied an Alexandria church. “Monte Carlo No More” describes efforts of a gun-slinging prosecutor to shut down illegal gambling in Arlington and Del Ray in the early 20th century. It features an action scene on the Long Bridge trolley line. “The Code Duello” plays out the events of a duel on Arlington ground between Henry Clay and John Randolph. “Ark of the Commonweath,” another favorite chapter of mine, reveals that floating brothels once parked at the Alexandria riverfront; the chapter also lists landing points of various brothel boats in D.C. and Virginia.

I wondered how Pope had unearthed and selected this particular collection of ten dramas that occurred in our neck of the woods. Perhaps he discovered these tales in the process of researching and writing his three previous books: Ghosts of Alexandria (2010); Hidden History of Alexandria (2011); Shotgun Justice: One Prosecutor’s Crusade Against Crime and Corruption in Arlington and Alexandria (2012). I may have to read them as well! I also want to see a regional map that pinpoints the location of some of these places, especially those, like Hell’s Bottom, that are long gone. As Pope says in his introduction, the hidden, wicked past lurks around us today, and I’d like to know exactly where! Maybe this will finally get me to the library to look for old maps. I’ve been meaning to do that for a long time…

Sign up for the Blue Virginia weekly newsletter

Sign up for the Blue Virginia weekly newsletter