Good stuff from the Commonwealth Institute:

Representation Matters: Why and How Virginia Should Diversify its Teacher Workforce

Strong relationships between students and their teachers are vital to a healthy learning environment. One of the most immediate ways these relationships are built is by students connecting with teachers who look like them. Unfortunately in Virginia, many students rarely or never have teachers who resemble them, which has adverse effects on both student perceptions of their learning environment and their academic performance. By investing in teacher preparation programs and partnerships at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and increasing teacher pay, Virginia can help break down the barriers that stand in the way of diversifying Virginia’s educator workforce.

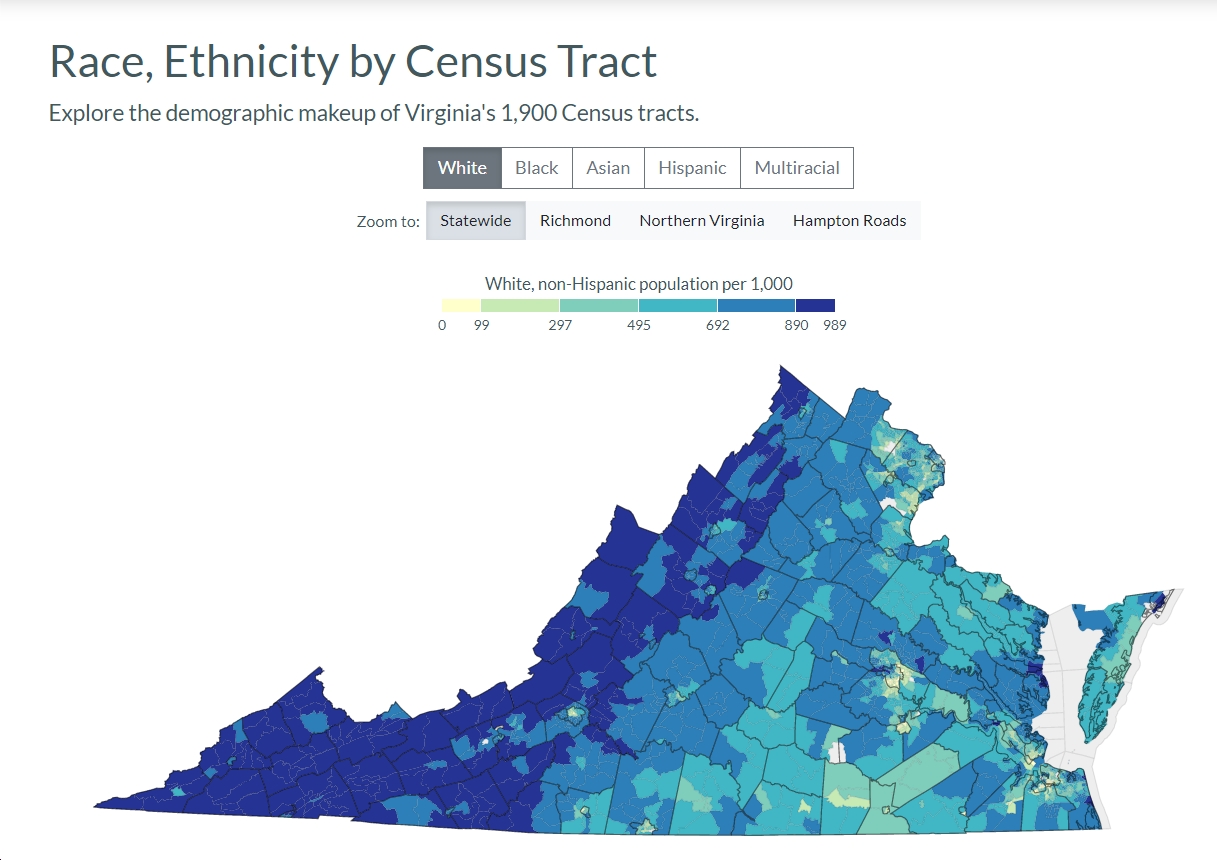

Currently, Virginia’s overwhelmingly white instructional staff does not reflect the diversity of the student body. In Virginia, over 75% of licensed teachers self-report as white, 11% as Black, and only 3% of teachers identify as Hispanic. Conversely, less than half of all Virginia students are identified as white, 22% are identified as Black and 16% are identified as Hispanic. If the current trend continues (in 2008, 57% of students were identified as white), this discrepancy may increase as Virginia’s student population grows more diverse.

Diverse learning environments benefit students overall, particularly Black students from low-income households. For Black students, the presence of Black teachers has been linked to improved attitudes toward their school, reductions in chronic absenteeism and school dropout rates, as well as increased levels of college enrollment. For Black boys in grades 3-5, the presence of just one Black teacher decreased their likelihood of dropping out of high school by 29%. For Black boys from very low-income households, having one Black teacher decreased their chances of dropping out by 39%.

Making sure that Black students have more than one Black teacher is also crucial to their academic performance. Black students in grades K-3 with just one Black instructor were 13% more likely to enroll in college than those who do not, according to a study by researchers at American University, Johns Hopkins University, and University of California Davis.And students who had two Black teachers throughout this age range were 32% more likely to enroll in college. Having a greater number of Black instructors has also been associated with decreased suspension rates for Black students, which could help reduce the problem of Black students being suspended at nearly 5 times the rate of Hispanic and white students in Virginia.

There is no quick fix to increasing the number of Black educators in Virginia. State leaders convened a task force on diversifying Virginia’s educator pipeline that laid out strategies to address this critical need and initial steps are being taken. This year, for instance, the Virginia Department of Education has awarded grant funds to assist over 300 provisionally licensed teachers of color to attain their full licensure. But more systemic change is needed.

A first step to diversifying the teacher workforce must be to collect accurate and detailed teacher demographic data. Currently, Virginia is only 1 of 6 states which does not require instructional staff to report their race or ethnicity. If staff supply information, the data can’t be made publicly available under Virginia law. Although many teachers report their race voluntarily, some choose not to do so which makes it difficult to gauge the full extent of the divide between students and teachers of color in Virginia. A more accurate measure would be a step toward finding solutions to better serve students of color overall in Virginia.

In addition to capturing more accurate information of the racial makeup of Virginia’s teachers, the state could help expand and strengthen teacher pipelines at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). Currently, 4 of the 36 colleges and universities with approved teacher preparation programs in Virginia are HBCUs. Yet HBCUs have been responsible for training more than half of the state’s Black prospective teachers in previous years.

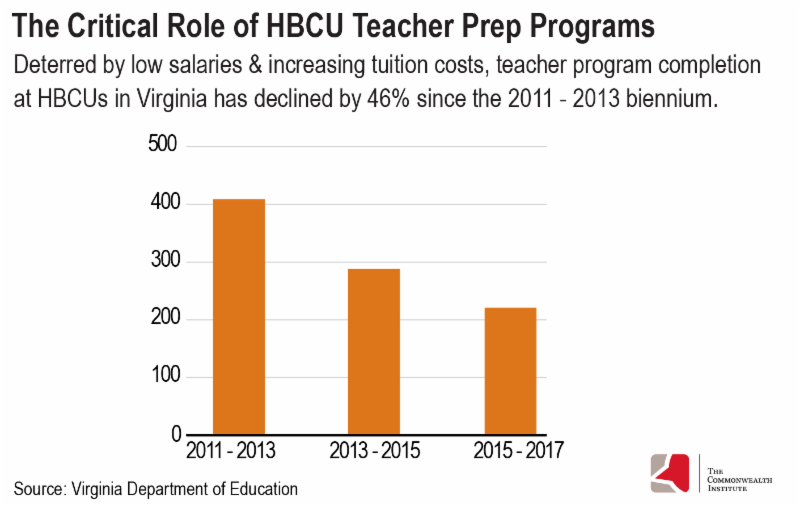

Virginia’s HBCUs are central to diversifying Virginia’s instructional staff and recruiting more Black teachers, including National Teacher of the Year Rodney Robinson who graduated from Virginia State University. And that is why greater state investment is needed so that more students of color are able to complete teacher preparation programs. Since the 2011-2013 period, the number of students completing an approved educator preparation program at an HBCU has decreased by 46% in Virginia. This decrease is largely associated with structural barriers as students of color have become increasingly deterred from teaching because of low salaries and increasing tuition costs.

There are three programs in Virginia — The Future Teacher Academy(FTA), Call Me MISTER, and the African American Teaching Fellows program. Only one, FTA at Norfolk State University, is housed in an HBCU in Virginia. Call Me MISTER, which provides tuition assistance, has had great success in South Carolina. With 13 chapters, this initiative is on track to double the number of Black male teachers in the state since its creation. Virginia has just one chapter in Virginia, located at Longwood University.

By making state investments in these types of programs across the commonwealth, particularly at HBCUs, Virginia would be taking more concrete steps toward its goal of diversifying the educator pipeline. However, diversifying Virginia’s educator workforce shouldn’t only be tasked to HBCUs. It should be up to all institutions with approved teacher preparation programs to take steps to diversify Virginia’s educator workforce.

With Virginia ranking below the national average for teacher pay, these reform efforts should be accompanied with significant raises in teacher salaries. Although recent legislation includes a slight increase in teacher pay, this is not enough to make teacher pay in Virginia competitive with the national average, let alone with other professions. In Virginia, instructors earn 31% less than comparable college-educated workers in Virginia – the 3rd worst teacher wage penalty in the country. This particularly deters Black instructors, who are more likely to have greater student debt, which contributes to greater dissatisfaction with their salary compared to white educators.

The initial steps that Virginia has taken are positive and should be pursued, but they are just a start. Stronger investments in preparation programs and providing competitive wages to teachers throughout the state are needed to ensure that educators in our schools are just as diverse as their students.

— Michael Johnson, Research Intern, and Chris Duncombe, Policy Director

![Virginia NAACP: “This latest witch hunt [by the Trump administration] against [GMU] President Washington is a blatant attempt to intimidate those who champion diversity.”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/gmuwwashington.jpg)