by Jeff Thomas

Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will. —Frederick Douglass

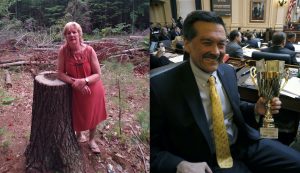

No event better illustrated the state of Virginia politics and government in the early twenty-first century than a sixty-one-year-old grandmother who confounded governors, CEOs, and the federal government when she was charged with trespassing on her own property. The most pressing issue on the minds of those officials in April 2018 was probably not Theresa “Red” Terry and her family’s cabin at the end of an unpaved road in Bent Mountain, Virginia. But it soon would be.

They hoped the Mountain Valley Pipeline would one day carry natural gas from Pennsylvania and West Virginia fracking operations to international export through ports on Virginia’s coast. The 308-mile pipeline was not popular among Virginians whose land would be seized, uprooted, and polluted so that investors could send out-of-state gas to India. Adding fuel to the fire was an unusual amendment to the Virginia Constitution that prohibited corporations from using eminent domain to take people’s land for private gain—corporations, that is, except for utilities. The Virginia legislature had been complicit in this land grab, from passing a 2004 law that guaranteed that “gas companies have the power to enter property without permission,” as Bart Hinkle of the Richmond Times-Dispatch put it, to twice passing the above amendment, as required by the state constitution, before sending it to the voters for final approval in 2012. For opponents, then, stopping the pipeline was no longer a matter of legislation but of justice.

The centuries-old farm had been in Red’s husband’s family since before the Revolutionary War, and she would be a witness to crews despoiling it with chainsaws and bulldozers. It was fair to call her headstrong when her husband nailed a stand and tarp thirty feet up a tree on their property, and she climbed it with little fanfare in late March 2018. When she began her vigil, nobody seemed to care, and construction crews felled the forest around her. “My daughter is also in a tree and had them on all four sides of her,” Red said. “She cried all day.” A local radio station covered her plight two weeks later, and on April 17, Blue Virginia published an activist’s video that drew thousands of views from the sort of people like you who follow politics every day. Red peered out from her stand and told a videographer, “I will come out of the tree when these people get off my land.” The next day, lawmakers from the area and northern Virginia held a press conference at the state capitol to express concerns over myriad issues with the pipeline, from contaminated water to eminent domain abuse to the treatment of Red and her daughter. One Nelson County resident said that the cooperation between rural and urban lawmakers was “very important. They have a lot of votes and a lot of swagger behind them that maybe those of us in rural areas don’t have.” Red responded that she was thankful for the attention, but she would prefer it be focused on the pipeline rather than her.

That same day, “a Roanoke County magistrate was signing their arrest warrants for trespassing and obstruction of justice.” The story went viral when reporters and readers heard a mother and her daughter were about to be arrested for “trespassing” on their own property. “They’re not taking my property without a fight,” Red said. Even more troubling were conflicting reports that they were being denied food and water and that local police told her husband that “he could leave food for his wife at the bottom of the tree, but she would have to come down to get it.” “They’re violating her basic human rights, by not letting her have food or water should she ask for it, or a hot meal should she ask for it,” her husband said. “You put someone in prison you feed ’em. Usually when you get to prison you’ve been tried and convicted. And she has neither been arrested, tried or convicted.” The spotlight swung over to the Roanoke Police Department, and its tactics put its leaders on the defensive. The Washington Post soon picked up the story under the headline “Perched on a Platform High in a Tree, a 61-Year-Old Woman Fights a Gas Pipeline.” The clickbait proved irresistible, and Red was the lead story on that paper’s national website on Sunday, April 22, 2018.

When I visited Red on April 23, 2018, her civil disobedience may have seemed much like she looked to those below: lonely, desperate, and doomed, but also inspiring, courageous, and just. A closer look revealed even more. To scan the crowd of fifty or so surrounding Red was to see how dire the situation was becoming not for the lone prisoner, but for the power brokers in Richmond and Washington who made the decisions that drove her there. There was a group of young and radical environmentalists who had at the beginning of the vigil erected a base camp around her. They ran the show, and nobody else would have been there without them. But among the crowd were photographers, civil rights attorneys, and Delegate Sam Rasoul of Roanoke speaking to a television crew. Staffers of Delegate Lee Carter and Senator Chap Petersen were there, and Jennifer Lewis, candidate for Congress and leader of an anti-pipeline group, was moved to tears. A newcomer to the crowd asked a series of bold questions of the organizers. “Who are you?” one finally asked him. “I’m Henry Howell. Do I need to say anything more?” said Henry Howell III, pugilist lawyer and son of the great politician who had come closest of any populist in the twentieth century to winning the Virginia governorship.

It is difficult to accomplish anything alone, which is why organizing is so important and so feared by those in power. In addition to the activists, who could be dismissed by those in power, the presence of the lawyers, media, and politicians personified the structural crisis facing the operation of Virginia politics and government in the second decade of the twenty-first century. Put simply, it was bad for business to raise electricity rates in order to bury explosive hazards throughout hundreds of miles of public forests and private land. Whereas a few days earlier, the Roanoke Police had been using hunger as a weapon to speed Red Terry’s arrest, that day, officers personally delivered her pizza and sandwiches.

“Appalachian politics are more eclectic than what the national headlines would suggest,” and an even deeper examination fleshed out the nature of the motley group. Professor Rhiannon Leebrick of Wofford College, whose research focused on social change and environmental issues in South Central Appalachia, noted that, contrary to impression, the “young and radical” organizers of environmental justice movements in rural Virginia possessed social networks, political sophistication, and economic capital that could be brought to bear on local governments and nongovernmental organizations to influence public policies. “The activists” had turned a small vigil into an international media scrum within a week.

In a system of government like Virginia’s where the laws were largely written by and for the powerful, lawyers would be key. Red’s civil disobedience, and the efforts of thousands of others who toiled without recognition, catalyzed the legal activism of those who knew that though the law had once worked for the pipeline, it could now be put into service against it. “My name is Henry Howell, Bar number 22274. Write that down!” he told a National Forest Service officer surveilling him with a telephoto lens, as he escorted Senator Petersen to other pipeline protesters that Petersen would soon file suit to protect. “All these brave, courageous, intrepid tree sitters must be wondering where their Governor and Attorney General are, as the economic powers of interstate, out-of-state pipeline companies are using our government to enforce a federal judge’s order for private companies to profit by taking people’s land,” Howell III wrote, as he outlined a case for court action.

Red came down after thirty-five days, but the truth was, she won the longer war, the details of which will be familiar to many readers, and some of you who are still even living them.

As a quick summary, in August 2018, the Roanoke Times reported on the fusillade of legal skirmishes that had begun since Red’s last stand.

“In Virginia and West Virginia, Mountain Valley has been put on notice six times since April that its measures to control erosion and sediment were failing, with muddy water sometimes flowing from work zones into nearby streams. Then in late July, a federal appeals court invalidated permits allowing the pipeline to cross through the Jefferson National Forest, faulting the U.S. Forest Service for not pushing for tougher erosion controls.…Then, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ordered a stop to all work on Aug. 3. The commission also this month ordered work to stop on the Dominion Energy–led Atlantic Coast Pipeline.”

In an extraordinary series of events on December 7, 2018, the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a stay for Atlantic Coast Pipeline construction; the Virginia State Corporation Commission, for the first time in history, rejected as not in the public interest the Dominion monopoly’s integrated resource plan for future infrastructure; and Virginia’s Attorney General Mark Herring sued Mountain Valley Pipeline alleging more than three hundred environmental pollution violations. Reflecting a heretofore unimagined political reality, Herring also chose this day to announce that he would seek the governorship in 2021. Days later, he pledged that he would never again accept any money from Dominion or its executives.

Crises of Power

In Dominion Energy, the intersection of money and politics in Virginia was at its most egregious, and it was worth examining as a window into state government. Dominion was essentially a state monopoly electric utility held within an investor-owned natural gas corporation; it could not fairly be called a private company, because two-thirds of its revenue and four-fifths of its cash came from the state monopoly. Virginia lawmakers guaranteed the utility a rate of return of roughly 10 percent that flowed to executives, Wall Street, and politicians. Despite this guarantee, Dominion had made a practice of overcharging Virginians by tens of millions or even hundreds of millions of dollars every year. Briefly, the State Corporation Commission, tasked with regulating state monopolies and power rates, had never once found that Dominion had charged fair rates. After a 2007 biennial refund law was enacted, more than $700 million was refunded to Virginians in 2010 and, in 2012, more than $70 million. Dominion passed a bill in 2015 that ended these refunds and consequently raised electricity rates on more than two million people and tens of thousands of businesses.

The fact that Dominion’s interests in high electricity rates ran counter to not just ordinary citizens’ but also small and large business interests may have seemed befuddling to some in this ostensibly pro-business state. But the paradox was resolved when one saw that Dominion was the state’s most profligate campaign contributor, and therefore, its lawyers wrote Virginia’s energy policies.

If the Virginia Way was “a euphemism for corruption,” then politicians with integrity were a foundational threat. The people in power never admitted to being swayed by activists or so-called ordinary citizens, but they always listened to criticism and protest. Always—because it affected the bottom line. In 2015, Dominion spokesperson David Botkins “could not name a piece of legislation in the past five years in which Dominion did not get what it wanted from the General Assembly.”

For the first time in history, in 2017, there was a true grassroots campaign in Virginia politics to elect people who pledged to never take campaign contributions or “gifts” from Dominion. Thirteen candidates who made this pledge won election. A bloc that large was significant, could sway votes, and could not be ignored. Because of the power of incumbency, some of these thirteen people would serve in office for many years. Dominion was the most powerful company in state politics precisely because it was the largest donor, and upstart politicians had little to lose and lots of good press to gain by pledging to not take Dominion’s dirty money. Activate Virginia and many others understood that giving money to politicians was the root of so many of the problems affecting state government, and the power of the idea was spreading throughout Virginia’s political system like a genie that could not be put back in the bottle. After the 2017 elections, “after two years of defending a controversial law that froze base rates for Virginia’s two largest electric utilities as a hedge against carbon regulation, Dominion Energy officials said Monday that it’s ‘time to transition away’ from the 2015 rate freeze.” By 2018, for the first time in history, Dominion could not get everything that it wanted. The backlash was too great; the threat of democracy was too real.

The Virginia Way was sold to the public as being good for business. Whether government should only exist to promote those interests was another question, but a business-centric theory of government and politics was at least comprehensible. America is, after all, a capitalist society; but the Virginia Way was about donors and politicians, and the Dominion-politician nexus functioned as an anti-business machine. Dominion was facing the most serious challenge in its 110-year history: politicians who supported it were being voted out of office. In a state that had putatively been run “of the businessmen, by the businessmen, for the businessmen” but was now run of, by, and for donors, Dominion was facing a crisis of democracy as conservatives and liberals realized independently that Dominion corrupted capitalism and government. “From a conservative standpoint, what bothers me here is the cronyism, one, and the further deviation from something approaching free-market pricing as we can achieve,” Tea Party leader Ken Cuccinelli told the Huffington Post. “It hurts everybody—it hurts the poor, it hurts business, it hurts opportunity.” Virginians on the left and right organizing together were an existential threat to Dominion’s true constituents and their spreadsheets in lower Manhattan. “For the first time, maybe ever, or for the first time in this era, Dominion is having to answer for things it does,” said political scientist Quentin Kidd. How Dominion responds to democracy—and how citizens will respond to Dominion—will chart the destiny not just of that company but of Virginia politics and government for the next decade and beyond. The ultimate nightmare for Dominion was that the politicians who had done its bidding since time immemorial would come to understand that Dominion’s self-interest in raising electricity rates was bad for business and hurt voters—or would come to be outnumbered by politicians who did.

The Bipartisan Consensus

Dominion’s machinations happened within an overarching bipartisan political consensus whose elements are clear to objective observers but rarely discussed openly, as if by doublethink. The modern Virginia political system was Senator Harry Byrd’s machine turned bipartisan. Harvard political scientist V.O. Key presciently noted that Byrd’s hegemony over Virginia politics in the middle of the twentieth century had instituted “an autocratic machine that may long outlive him.”

Virginia did not share West Virginia’s history of New Deal populism and labor organizing, except in the far southwest, resource-extractive areas. North Carolina had to some degree embraced forward-looking education and business policies in the decades after desegregation, especially at the University of North Carolina and in cosmopolitan Charlotte. Virginia instead pursued a bipartisan economic consensus more comparable to the reactionary Deep South, just with more money and less overt racism. Robert Caro wrote:

““The Byrd machine is genteel,” the liberal Reporter magazine had to admit. “There are no gallus-snapping or banjo-playing characters in Virginia politics.” Its hallmark was courtliness, not the demagoguery prevalent in other southern states. “Virginia breeds no Huey Longs or Talmadges,” John Gunther wrote in Inside U.S.A. “The Byrd machine is the most urbane and genteel dictatorship in America.” “He hated public debt with a holy passion,” [U.S. Senator Paul] Douglas was to write of Byrd. “With little or no sympathy for poor people, and instinctively on the side of the rich and powerful, of whom he was one, he nevertheless had a certain rugged personal honesty and a genial air of courtesy towards his opponents, except when severely pressed.” While he ran the [Senate Finance Committee] graciously, however, he ran it unyieldingly. “He had a habit of slapping” a fellow senator on the back and laughing, “as if they were both enjoying a good joke,” while he was denying a request.…His economic philosophy was a businessman’s philosophy. No one ever called him a reader or a particularly deep thinker, or even a man with more than a surface understanding.”

The Byrd machine’s paternalism and even its mannerisms were easily recognizable in Virginia’s political circles well into the twenty-first century.

The state followed this well-worn path even as Democratic Party hegemony bifurcated in the mid-to-late twentieth century and evolved into what was effectively one-party dominance by the Money Party, with a Republican and Democratic wing.

Key and others contended that Byrd’s political organization practiced relatively clean government and was not known for graft. However, Brent Tarter, founding editor of the Dictionary of Virginia Biography, pointed out that the machine was so efficient that its practitioners “did not need to steal money because they had already stolen something a lot more valuable: they had stolen democracy.” Outright graft was less common in Virginia because its politicians controlled public policy so thoroughly that they could just write the laws to directly benefit themselves. The constitutional amendment permitting gas companies to legally trespass on people’s land while labeling its owners as trespassers was a quintessential example.

The Virginia political system in the twenty-first century was as deeply entrenched as the Byrd dynasty from which it descended. In the two party era, since the civil rights movement secured voting rights for the disenfranchised 20 percent of Virginians, Virginia politics and government had operated with bipartisan consensus. There was division on social issues, such as abortion, gay marriage, and gun rights, but on the economic issues that mattered to businesses and the bottom line, there was and always had been unity among the parties, with rare exceptions. For a long time in Virginia, it did not really matter whom citizens voted for on economic issues, because both parties would give them the same. As the descendant of a system in which the powerful wrote laws to benefit themselves, state politics still reflected the will of business and campaign donors. The most incisive way to cut through the daily noise and truly comprehend Virginia politics and government was to understand that politicians were doing what their donors wanted and donors got what they paid for: low taxes, underfunded public services, hostility to workers and unions, low public welfare and high corporate welfare. The Virginia Way was not broken; on the contrary, it worked exactly as it was designed as a way for politicians and donors to maintain their lucrative, symbiotic monopoly on power.

Political scientists often argued for a median voter theorem in which elections and policy were determined by the midpoint of a bell curve distribution of voters. In this theory, politicians moved to centrist positions to capture the largest share of the electorate. In Virginia, this mode of electioneering only existed with social issues and minor, soon-to-be-forgotten faux controversies like this week’s Jamestown kerfuffle, which were given disproportionate weight by antagonistic reportorial styles and partisan electioneering that accentuated wedge issue conflicts. The political and economic affairs of the state were not on a Bell Curve but were bimodal, and Republican and Democratic politicians were on the same side, generally opposed to the public. For example, the business-political class got what it wanted with electoral and fiscal policies, even though measures like expanding voting rights and increasing the minimum wage were supported by a substantial majority of the population (69 percent and 74 percent, respectively). A corollary was that the bipartisan consensus meant politics was commodified: for sale to the highest bidder. Thus, there was little difference in the economic programs of the two parties because they were both beholden to the common interests of their donors. With the exception of Reconstruction, there was, and always had been, a bipartisan economic consensus supporting the Virginia Way.

Even into the twenty-first century, the real work of government was largely predetermined; the bipartisan consensus gave voters the illusion of choice at the polls. Virginia’s budget changed little when a governor from one or the other party came into office. The economic programs of Democratic governors were mostly indistinguishable from their Republican counterparts, or from Dwight Eisenhower’s, for that matter. Whether voters faced a promise-breaking regressive tax increase to pay for transportation and infrastructure under Warner in 2004 or Republican Bob McDonnell in 2013 was mostly arbitrary and was determined more by legislative leaders’ personal psychodramas about which executive they happened to like. In one glaring example, Terry McAuliffe, the hard-charging New York transplant, unsuccessfully worked the Republican legislature for four years to accept the 100 percent federal funding available to expand Medicaid health insurance for the working poor, a measure that was supported by business interests in Virginia. He was succeeded by Ralph Northam, the soft-spoken doctor and son and grandson of Virginia judges, and within the first six months of his term, the Republican legislature accepted now-diminished 90 percent funding for Medicaid expansion, with Virginia’s 10 percent contribution coming from raising taxes on hospitals. It can fairly be said that the Northam scandal – whether or not one thinks the photos are him, he readily admits to having the vile ‘nickname’ Coonman, as if that was normal – has had no lasting effect on his ability to govern.

In a two-party society, there was no way to vote against policies on which the parties aligned. It was not a coincidence that Barack Obama and Donald Trump had both run as outsiders trying to clean up Washington, and their slogans reflected a poll-tested yearning of Americans for political change. Increasingly over the last five years, disaffected voters from all sides of the political spectrum attacked the sclerotic Virginia Way. This precipitated a grassroots backlash on the progressive and Tea Party sides of the Democratic and Republican Parties in which activists increasingly shared the same language and even the same goals. Attendees at political events and consumers of grassroots media would notice a surprising overlap in rhetorical frames among members of progressive and Tea Party groups that both criticized establishment politicians for wasting taxpayer money on projects that benefited donors primarily. More than rhetoric, the specific issues on which these groups organized were sometimes entirely in accord. It may have surprised members of both groups to learn that Activate Virginia, created by former Bernie Sanders national delegate Josh Stanfield to oppose Dominion’s legislative influence, and the Virginia Tea Party, which was so strongly opposed to Dominion that the company’s 2018 bill was, along with Medicaid expansion, one of just two issues the group marked on its legislative scorecard that year, were working toward the same goal and offered the same critiques of that company’s political power. At the same time, Virginians were living in a country increasingly divided along political, media, and social media lines. As a consequence, practical efforts toward common cause that honest people could find as a solution to the Virginia Way were almost nonexistent. As much as donors and their political power were uniform across the parties, the activist groups in Virginia remained partisan and siloed, to the continued benefit of the bipartisan consensus.

The Virginia Way in 2019

Followers of current events may have had the impression that the biggest stories in Virginia politics were the 2017 and 2018 “blue wave” elections.

These were undoubtedly important, but the biggest story in Virginia state politics in the first two years of President Trump’s administration was not the backlash to him but the backlash to the Virginia Way. This antidemocratic bipartisan consensus was lauded, for example, by former state senator John Chichester:

“In large part, the “Virginia [W]ay” is rooted in the deep sense of responsibility that goes with occupying the space of our founding fathers—those who shaped this great nation with a bold vision that continues to inspire the world.…We can take comfort in the lessons of Virginia history. At those crucial points in our journey, Virginia’s political leaders will reach deep and find fortitude and courage. They will coalesce and make that unpopular choice, if it truly is necessary to preserve the treasure that is our Commonwealth.”

It was rare to see an American politician so openly bash democracy in favor of elitist rule. The more accepted stance was to pay rhetorical homage to “all men are created equal,” and this was even exaggerated in Virginia, where native son Thomas Jefferson designed both the state’s capitol and first university. While all are indeed created equal, another truism was that “different interests necessarily exist in different classes of citizens,” as written by native son James Madison.

Another definition of the “Virginia Way” is provided in an essay just out by native Virginian Drew Gilpin Faust, President emeritus of Harvard.

“But elite white Virginians created a narrative of an invented past and a distorted portrait of their own time to reassure themselves of the justice of their social order and of their own benevolence. The cult of the Lost Cause embraced an apocryphal history suffused with nostalgia for a world of valorous Confederates, kindly masters, and contented slaves. And it mischaracterized the present, extolling the “Virginia Way,” a distinctive form of Jim Crow in which blacks and whites lived peaceably together in lives of “separation by consent,” in the words of Douglas Southall Freeman, a Richmond newspaper editor and renowned Robert E. Lee biographer. Freeman acknowledged that this was a social order designed to perpetuate “the continued and unchallengeable dominance of Southern whites,” who, he told his readers, would work to provide assurance of safety and security to black Virginians in return for their acquiescence in the status quo.”

Faust accurately shows that the Virginia Way is merely the dominant political-economic narrative of the ruling class, whether pro-business, or pro-segregation, or pro-slavery; new facts are subsumed into the old ideology. It calls back not to Jefferson but to Madison, who argued at the Constitutional Convention:

“The man who is possessed of wealth, who lolls on his sofa or rolls in his carriage, cannot judge of the wants or feelings of the day laborer. The government we mean to erect is intended to last for ages. The landed interest, at present, is prevalent; but in process of time, when we approximate to the states and kingdoms of Europe; when the number of landholders shall be comparatively small, through the various means of trade and manufactures, will not the landed interest be overbalanced in future elections, and unless wisely provided against, what will become of your government? In England, at this day, if elections were open to all classes of people, the property of the landed proprietors would be insecure. An agrarian law would soon take place. If these observations be just, our government ought to secure the permanent interests of the country against innovation. Landholders ought to have a share in the government, to support these invaluable interests and to balance and check the other. They ought to be so constituted as to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority.”

The money that flowed to politicians and the hubris that they were “occupying the space of our founding fathers” when they did something “unpopular” conflated to make the Virginia Way a seductive ideological space. Virginia politicians passed no state laws beyond disclosure to guard against unethical behavior. “Virginia is the only state where lawmakers can raise unlimited campaign donations from anyone, including corporations and unions, and spend the money on themselves,” a reporter noted. What did this temptation invite?

The legislature was, as Madison wanted, the most powerful branch of government, and the leaders of the Virginia House and Senate represented its apotheosis. Senate Democratic leader Dick Saslaw expressed his perceived role in a debate with his Republican counterpart as if they were in a contest: “Go ask Dominion, go ask any of these companies—beer and wine wholesalers, banks, the development community—every one of them will tell you, they will tell you I’m the most pro-business senator.” Senator Saslaw, despite four decades of experience and more than a million dollars in cash from those same “companies – beer and wine wholesalers, banks, the development community,” and his largest donor, Dominion Energy, could not win a plurality in his own district in a 2019 primary and was nearly upset by a truly grassroots campaign by human rights lawyer Yasmine Taeb.

Senate Republican leader Tommy Norment took things a step further and was literally in bed with a lobbyist; his long affair with one was disclosed only when a former client filed an ethics complaint against him. During the time in which he was committing adultery, itself a Class 4 misdemeanor in the state, Norment not only failed to recuse himself from voting on lobbyist Angela Bezik’s bills but also was the leading sponsor of two of them.

When the scandal broke in 2015, Norment claimed that he and his wife “were able to work through our issues including me having to share with her some of my misbehaving which was painful but necessary for a reconciliation. We are doing quite well now without any issues.” Norment soon divorced her. On June 16, 2018, he announced that he was engaged to Bezik, who was still employed as a state lobbyist.

On the same day as Norment’s engagement news, Speaker of the House Bill Howell announced that he was taking a job at McGuireWoods, Virginia’s most powerful lobbying firm. “Although state law forbids Howell from lobbying his former colleagues in the General Assembly for one year, Howell started a job Monday in a non-lobbying capacity as a consultant with McGuireWoods Consulting,” Patrick Wilson wrote. “A weak definition of lobbyist in Virginia allows Howell to advise clients on how they can influence his former colleagues, and allows him to call former colleagues in the legislature to request appointments for clients.” Howell was reportedly “the first former House Speaker” in Virginia history to turn to “consulting.”

Norment and Howell knew very well what was moral; in fact, they had publicly written about their vision of good government and the perils of corruption in a joint essay just a few years earlier:

“Public service requires loyalty—not to a party or an ideology, but to those we serve. Public service also requires sacrifice. While that sacrifice is often measured in time away from family, it is more than that. It is an unconditional and unequivocal promise to place the best interests of the commonwealth before oneself. Public trust and the integrity of elected leaders are essential to the success of representative democracy. When the public loses confidence in those processes and those entrusted with significant responsibility and power, the system can crumble.”

It was disconcerting in the state that was “the birthplace of the constitutional right to a free press” to see the contempt of the people and the press evidenced so brazenly in Norment and Howell’s simultaneous statements; Norment’s story was eclipsed by Howell’s. It well illustrates a common theme in Virginia: the vast disconnect between words and actions in service of the Virginia Way. Some people chose to believe the words; some people looked at actions.

The true meaning of the Virginia Way was clear for those concerned with reality rather than ideology. Robert Zullo left the Richmond Times-Dispatch in 2018 and formed the Virginia Mercury with three other political reporters. He shared his motivation in “Meet the Mercury: A New Look at the Virginia Way”:

“For his enthusiastic support of the “big boys,” other delegates in the House jokingly branded the amiable [Delegate Terry] Kilgore a “reverse Robin Hood” and gifted him with a trophy stuffed with fake cash and festooned with corporate logos in a surreal scene that might have managed to capture everything wrong with how business is done at the Capitol. “It’s all in good fun,” Kilgore said. Sit through enough legislative committee meetings and you’ll see a steady stream of common-sense bills that could benefit regular people swatted down like flies day in and day out during the session. Generally, their fatal flaw is that they might make a business, insurance company, landlord or other entity with a powerful paid lobbying organization do something it doesn’t want to.”

A poll showed that just one in three Virginians felt that Virginia politicians were “exceptionally” or “mostly” honest. “Clearly, the idea that Virginia has an exceptionally ethical and honest political culture is a figment of the imagination,” said political scientist Quentin Kidd. “The public simply doesn’t buy it.”

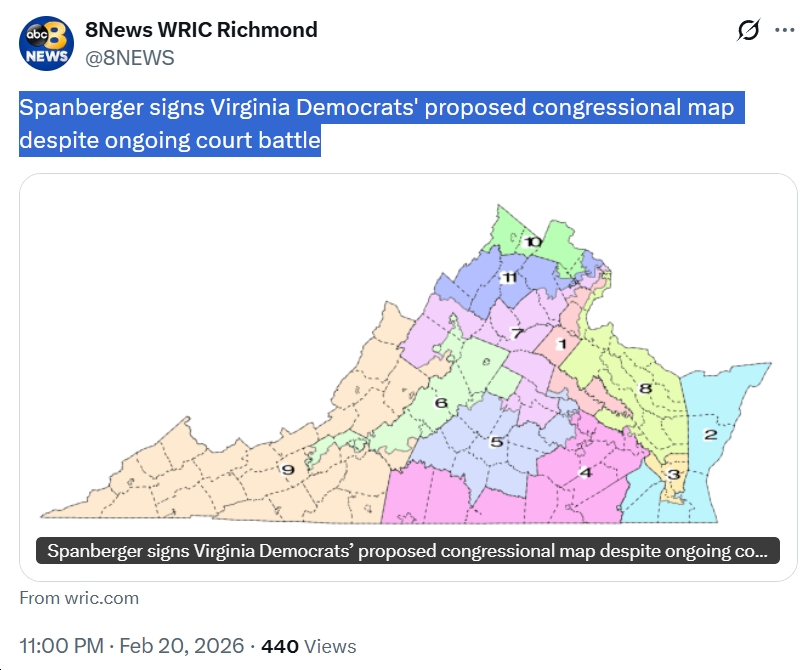

Thus, running against the Virginia Way proved a successful political strategy for legislators, and voters increasingly elected people who rebelled against the pay-to-play system of the state’s politics. The Virginia Way was effective at reconstituting itself, but self-aggrandizement was far from sufficient. Entrenched power also relied on anti-democratic principles. For the first time in the long history of the state, in November 2015, every politician who ran for reelection won, an incredible 122 out of 122. The fact that 2017 witnessed a landslide election for Democrats, but the House of Delegates remained precisely equally divided, showed the continuing power of gerrymandering.

The years 2016 to 2019, from President Trump’s election through the aftermath of the present, represented both populist and elite backlashes to the operation of the so-called Virginia Way, the corporate-centric philosophy by which state government had been run since colonial times. The internal contradictions of this system had come to harm not only the working and middle classes, as the Virginia Way always had, but also the ruling class itself. Dominion Energy, which had ruled the roost as Virginia’s most powerful corporation for generations, was facing the most serious challenges in its history, from people who could not and would not be ignored. Virginia’s political class was facing the greatest upheaval since the days of Henry Howell Jr.—and perhaps since Reconstruction a century before that. Virginia was changing, but the political and business elites were still the descendants of the tobacco planters who ruled a government “of the businessmen, by the businessmen, and for the businessmen.”

***

This is the second of a three-part essay on the Virginia Way.

Part 1 – Historical Myths Constrain Our Present Reality

Part 3 – Living Faith in Virginia

See also Lowell Feld’s review, “I wrote the book because I believe in the promise of Virginia.”

Jeff Thomas is the author of The Virginia Way: Democracy and Power after 2016, from which this essay is adapted.