by Jeff Thomas

I would love to see us do our own work and be proud to be Virginians. — Reverend Ben Campbell

***

From Virginia’s founding, the same people who have controlled the government also owned the state’s resources. The nature of political power over four centuries did not substantively change even as capitalism transformed the seats of economic wealth from dynastic families to immortal corporations. How did this happen?

The “great men” invented a state religion called the Virginia Way to control the population.

One could discern the echoes into modernity when objective observers assessed Virginia government. There are two events in which Virginia’s political establishment reacted very differently from places with worse reputations for racism and corruption. In the first, after Confederate iconography led to violence, Charleston and New Orleans took down their divisive symbols, but the monuments in Charlottesville and Richmond, easily the most prominent Confederate statues in the world, remain untouched. In the second, after pay-to-play admissions scandals, the flagship universities of Illinois and Texas launched independent investigations that quickly led to their presidents’ resignations, but the University of Virginia did nothing but dissemble about its wealth-based affirmative action.

There were many more examples to show Virginia’s true character compared with its deification. In the national Health of Democracies project, Virginia was ranked fiftieth out of fifty-one states and D.C., earning particularly low marks on voting rights and campaign finance. A 2012 survey by the nonprofit Center for Public Integrity, Public Radio International and Global Integrity on honest government in the states gave Virginia grades of “F” for legislative accountability and campaign financing. “A lack of laws and effective regulation to keep legislators from using public funds for themselves, ineffective regulations about the gifts legislators get, their financial disclosures, the work legislators do when they leave office and granting jobs or favors to family or cronies help put Virginia near the bottom when it comes to the risk of corruption, as does the lack of any limits on campaign donations,” the survey said.

An updated survey in 2015, after the McDonnell scandals, ranked Virginia sixteenth out of the fifty states, with F grades for public access to information, campaign financing, and lobbying disclosures. The last several years have also seen some limited electoral progress for women. While Virginia was dead last in gender equity among elected officials in 2013, in 2018 it had climbed to thirty-seventh out of fifty. Interestingly, while Virginia ranked fourth-, tenth-, and sixteenth-worst on three quantitative corruption measures in an analysis on the website FiveThirtyEight.com, its subjective reputation for corruption among reporters was a respectable sixteenth-best. Workers also were not faring well in Virginia’s economy, as “Virginia is now the most unequal state in the country, and is more unequal than at any time on record,” the Commonwealth Institute reported in 2016. The humanitarian aid group Oxfam ranked Virginia dead last of the fifty states and D.C. in its 2018 report on “the best and worst states to work in America.”

America made progress to realize the promise of a government of, by, and for the people, but what gains Virginians had achieved had largely come from without. The Union army ended slavery, and federal courts had to step in to integrate schools, to open public universities to women (Virginia Military Institute in 1996; the University of Virginia in 1970), and to permit interracial marriage in 1967 in Loving v. Virginia. Virginia did not itself grant women the right to vote and did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1952; it affected the state only when passage in other states thirty-two years earlier caused it to become part of the federal Constitution.

Attorney and lobbyist Frank Atkinson looked at the state’s four hundred years and saw something far different when he wrote his own history of modern Virginia after a career revolving between advising governors and McGuireWoods. Two days after Ralph Northam’s odious yearbook photo metastasized around the world, Atkinson published an ode to Virginia in the Richmond Times-Dispatch:

“Four centuries ago, representative government was first planted at Jamestown; Africans first arrived; women were first recruited; entrepreneurship began to flourish; and a Thanksgiving tradition was born.”

James Branch Cabell’s passage from 1947 was just as descriptive in 2019:

“Of beauty and of chivalry and of gray legions they spoke, and of a fallen civilization such as the world will not ever see again, and, for that matter, never did see; of a first permanent settlement, and of a Mother of Presidents, and of a republic’s cradle, and of Stars and Bars, and of yet many other bygones, long ago at one with dead Troy and Atlantis, they babbled likewise, for interminable years, without ever, ever ceasing.”

Virginia’s bizarre collective unconscious predated the Civil War, which was merely subsumed into the narrative. When Frederick Law Olmsted visited Richmond in 1854, he had written:

“What a failure there has been in the promises of the past! That, at last, is what impresses one most in Richmond.…[It] is plainly the metropolis of Virginia, of a people who have been dragged along in the grand march of the rest of the world, but who have had, for a long time and yet have, a disposition within themselves only to step backwards.”

When the king’s rules were being rewritten in 1787, Saint Madison understood the threat that great wealth faced from democracy:

“[I]f elections were open to all classes of people, the property of the landed proprietors would be insecure. An agrarian law would soon take place. If these observations be just, our government ought to secure the permanent interests of the country against innovation. Landholders ought to have a share in the government, to support these invaluable interests and to balance and check the other. They ought to be so constituted as to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority.”

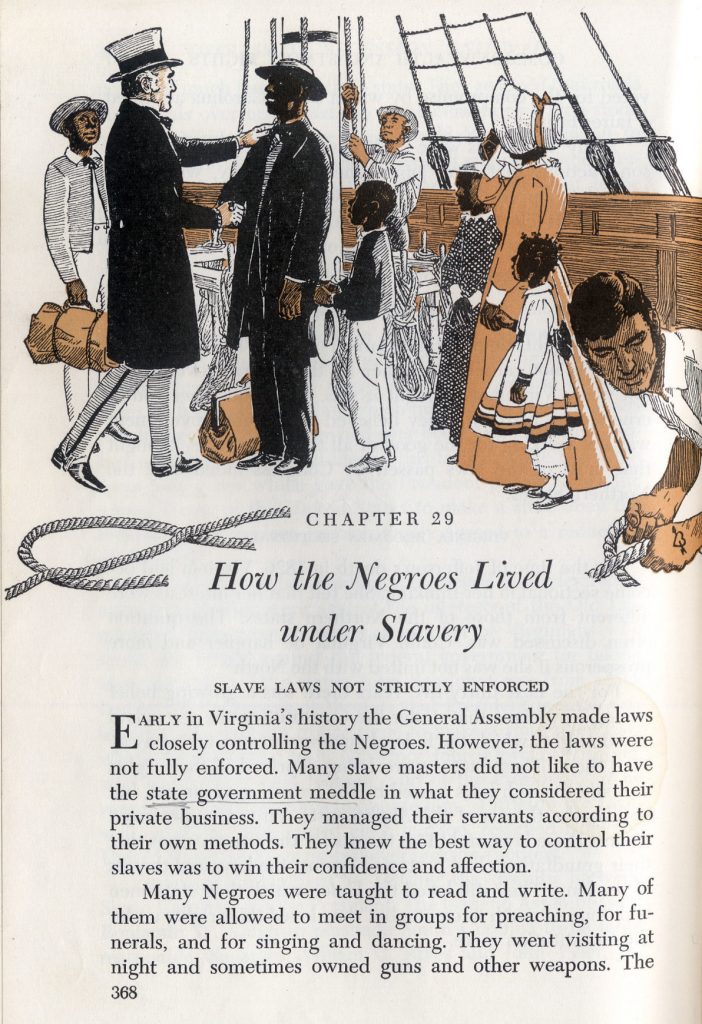

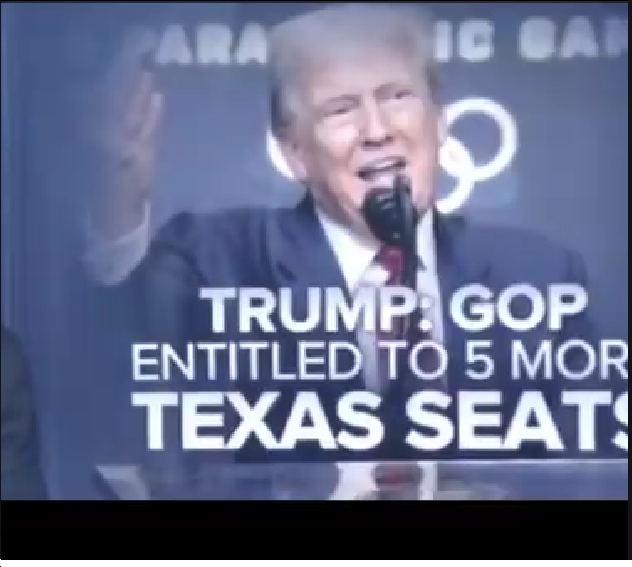

The Virginia Way catechism has an economic purpose. The most successful pursuit of Virginia landowners has been to maintain their wealth and power by promulgating an all-encompassing ideology that infuses society with unearned reverence for and unquestioned obedience to them. Throughout its history, Virginia has engaged in “a battle against its own denial.” In 2019, a high priest chanted in the face of a racist scandal revealing Virginia to the world that “representative government was first planted at Jamestown; Africans first arrived; women were first recruited; entrepreneurship began to flourish; and a Thanksgiving tradition was born” in Virginia in 1619; his creation myth echoed the government’s textbook from the mid-twentieth century, those scribes’ revisionist fathers, their defeated grandfathers, their half-revolutionary forefathers, and ideological justifications dating to colonization. Once one saw the reality behind the myth of the faith, it could not be unseen; witness the dehumanizing textbook and Stalinist levels of propaganda that Virginia government mandated in public schools from the 1950s to the 1970s.

Through the early twenty-first century, Virginia has adopted a bipartisan machine politics in which Republicans and Democrats are two factions of one Money Party. There are individual dissenters, but it is accurate to state that the Virginia legislature hhasad not deviated much from that one-party dominance for four centuries, with one notable exception.

From 1882 to 1884, Virginia was led in the legislature and Governor’s Office by a biracial coalition known as the Readjuster Party. The Readjusters’ platform was to stop Wall Street from dictating the usurious terms by which Virginia would pay back public debts dating to long before the Civil War.

Instead, Virginia would pay the bankers on more reasonable terms that would allow investment in public schools for white and black children. This popular governing coalition achieved many of its goals over just two years before Democrats used a riot to inflame racial tensions a few days before the 1883 elections. Democrats won these elections and instituted their reprehensible segregationist policies that would last nearly one hundred years and continue de facto into the present.

Virginia government is renowned for its gentility because its leaders couch vile policies in soft language, but the truth is that the people with power in Virginia are and always have been reactionary; the power elite in Richmond, where the Virginia Way is and always has been most deeply ingrained, is extreme even within the state. The ascendance of the Virginia Republican Party after desegregation helped attenuate the worst facets of Pope Byrd’s segregationists, but any moderate reformist impulses had long since been purged in service of the state religion.

At the same time, there has always been a hint of Virginia populism, crushed all but once, and in 2019, it has reached an apogee not witnessed by Dominion’s corporate papacy in forty years: a crisis in managed democracy, and an old threat to the new mandarins. Dominion lobbyist Bruce McKay put it well as his company launched “a campaign to elect a pipeline” and “compiled a ‘supporter database’ of more than 23,000 names, generated 150 letters to the editor, sent more than 9,000 cards and letters to federal regulators and local elected officials, and directed more than 11,000 calls to outgoing Gov. Terry McAuliffe and Virginia’s U.S. senators.” “Nowadays [regulators] are being bombarded by general citizenry, by elected officials who have asked to insert themselves into the process, and this debate swirls around,” he said. “Historically non-political processes [are] now political.” It may have seemed to him that Dominion’s influence-peddling was “nonpolitical,” but to be more accurate, its unquestioned monopoly on political power was being challenged by Virginians who had every right to demand answers from their government. In 2015, spokesman David Botkins “could not name a piece of legislation in the past five years in which Dominion did not get what it wanted from the General Assembly.” When politicians were no longer beholden to its corrupting money in 2018, the “great men” had to pretend, for the first time, that the people were on their side; rather than changing course, they manufactured a fake congregation to claim the sun revolved around the earth.

The Virginia Way was sold as a formula for growth, but it functioned as a straitjacket holding people back from their God-given potential. The architects had constructed a tenuous artifice of policies and governance that benefited themselves, but there were many more Virginians who lived their faiths by helping others.

Reverend Ben Campbell has devoted his life to healing the wounds that were causing so much suffering. He notes:

“The problem with Virginia that hurts me deeply—and my family has been here since 1760—is that I actually believe in the idealism and values of this state. I believe in the Declaration of Independence. There are some great things that have happened here. And yet, the only times we have been able to live up to those values are when we made the Yankees do it to us. It took the defeat of our people to end slavery, and it took the defeat of our people to make us overcome racial segregation in schools. And as soon as the Yankees left, we did it all over again. I would love to see us do our own work and be proud to be Virginians.”

James Ryan, the adopted child and first-generation college student who has ascended to the UVA presidency, loves Virginia and studies its past and present to learn how we as a people can do better. “You’re going to feel a lot of pressure to conform, whether in your workplace or in your neighborhood, in raising your kids or in creating your relationships,” Ryan said in a speech to students. “Don’t be afraid to do what you think is right. Don’t be afraid to speak your mind. Don’t be afraid to do what you think is fun, to do what you think might work, to do something that hasn’t been tried before.” In his inaugural address, he announced to a cheering crowd that Virginia undergraduates from families making less than $80,000 a year would no longer pay tuition to attend UVA, and those from families earning less than $30,000 would no longer pay for tuition, room, or board. We want to be “not just great, but good,” he said.

“[T]he faith I would like to discuss is of the secular variety. It’s the faith of the Emily Dickinson poem: “The pierless bridge supporting what we see unto the scene that we do not.” The faith that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. described as taking the first step, even when you don’t see the whole staircase.…I have faith that we will be an even stronger university than we are today, and we will have done some good in the world as well. But we will forever remain an unfinished project, just as this nation, whose founding is bound with our own, will also remain unfinished. That fact should not dampen your faith but instead strengthen your resolve. We may never be finished, but we can certainly make progress. The future awaits us, albeit impatiently, and it remains ours to shape.”

The tuition changes were effective immediately. “And, like most speeches during Ryan’s time so far on Grounds, he ended with an anecdote that balanced humor with heart,” a reporter wrote. “Sticking Nike Flyknits out from underneath his black regalia and robes, Ryan asked university presidents, faculty, students and supporters to join him on a mission to make UVA better. ‘Friends, my running shoes are laced up.’”

At the end of the second decade of the twenty-first century, we can know with confidence that Virginia government is still for sale to the highest bidder, yet the system in 2019 has the chrysalides within itself to undergo the most significant metamorphosis since desegregation, and perhaps since Reconstruction. It is neither written in our genes nor the stars that the few Virginians who dedicated their lives to wealth accumulation also have to control the people’s government.

People who are lucky enough to have freedom face a moral choice of who they are and who they would become. “Live as free people,” Saint Peter wrote, “but do not use your freedom as a cover-up for evil.” “If you’re not out there trying to solve the problem, you are the problem,” Paul Goldman said. “You can’t just wish something to happen—you have to actually go out and do it.”

What should be done? There are no perfect answers, other than to use precious freedom that so many Virginians have never had to solve problems that nobody else is solving. In this way, ordinary people can win extraordinary victories.

***

This is the final installment of a three-part essay on the Virginia Way.

Part 1 – Historical Myths Constrain Our Present Reality

Part 2 – New Threats to Old Powers

See also Lowell Feld’s review, “I wrote the book because I believe in the promise of Virginia.”

Jeff Thomas is the author of The Virginia Way: Democracy and Power after 2016, from which this essay is adapted.