by Triston Chase O’Savio (“Litigation Attorney at an AM Law 100 Firm, Former Law Professor @dickinsonlaw, Advocate For Civil Rights, Former Federal Judicial Law Clerk.)

by Triston Chase O’Savio (“Litigation Attorney at an AM Law 100 Firm, Former Law Professor @dickinsonlaw, Advocate For Civil Rights, Former Federal Judicial Law Clerk.)

Get Out To Vote: Our Democracy Depends On It

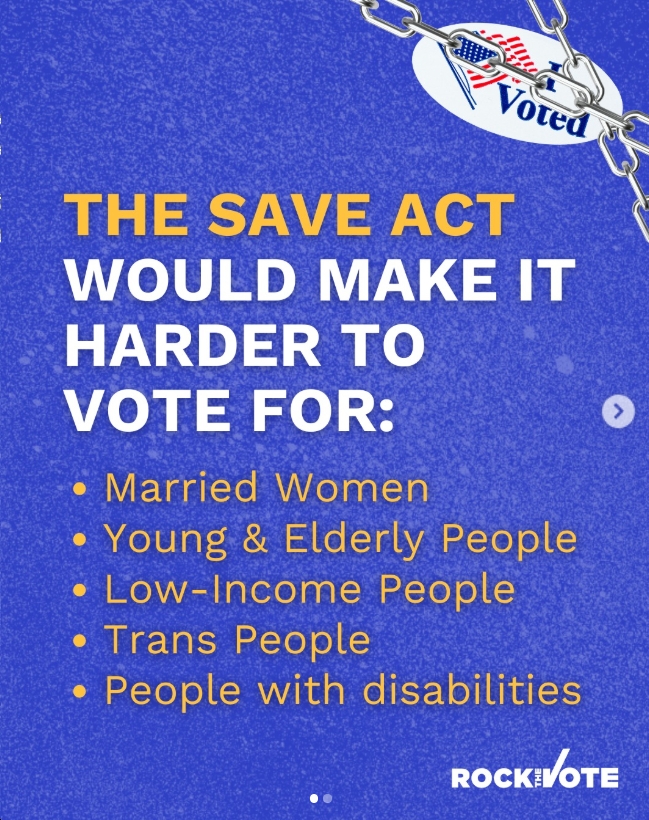

With just few days until the Virginia midterm elections, every eligible voter needs to understand that the foundation of our democracy is at stake. Our country has never equally guaranteed the right to vote to all citizens. We are now at a crucial moment in history, as states are gradually eroding voting rights that have taken centuries to establish, the Supreme Court is failing to protect our rights, and unfounded claims of widespread voting fraud have tarnished the integrity of our electoral process. We need as many eligible voters to participate in our democratic process as possible, if we ever want our government to truly represent the will of the people.

Voting was not traditionally recognized as a right in this country. Even after constitutional amendments were passed which gave women and Black citizens the right to vote, state and local governments continued to use legislation and intimidation as tools to impede and dissuade many people from voting. The most notorious examples appear at the end of the Reconstruction era, when states across the South began implementing new laws that severely restricted the voting rights of African Americans.[1]

In 1965, Congress enacted the Voting Rights Act, which outlawed discriminatory voting practices which have the purpose or effect of discriminating on the basis of race.[2] The Voting Rights Act vastly and immediately improved voter turnout for Black Americans. By the end of 1965, nearly a quarter of a million new Black voters had registered to vote. [3] The Voting Rights Act also required states with a strong history of discriminatory voting practices, such as Virginia, to receive preapproval from a federal court or the Department of Justice before enacting new voting laws.[4] This was the established law for nearly 50 years, until 2013, when the Supreme Court gutted this preclearance requirement in the Shelby County v. Holder decision.[5] Since then, states with a history of racially charged voter discrimination have been afforded unfettered discretion to create voting rights laws without proactive federal oversight, including laws that disparately impact communities of color.

Unfortunately, there are numerous modern laws which have been passed under the façade of neutrality and upheld, despite devastating and unjust consequences in reality.[6] Voter purging laws and inequitable gerrymandering are notable examples.

Several state legislatures have enacted laws to remove registered voters from their voting rolls after a period of inactivity, despite clearly disproportionate effects on communities of color. As a result, previously registered voters sometimes show up at the polls, only to be told that they cannot vote. In 2018, the Supreme Court deemed this practice acceptable, in the Husted v. Philip Randolph Institute decision.[7] It upheld Ohio’s “use-it-or-lose it” voting law, which allowed the state to strike voters from the registration rolls if they failed to vote for four years or two federal election cycles.[8] Urban African American neighborhoods had 10 percent of their voters removed, as compared to only 4 percent in the suburban, predominately white neighborhoods.[9]

Inequitable Gerrymandering has also created devastating outcomes for voter representation in America. Gerrymandering is a process that occurs every ten years that allows states to redraw their legislative and congressional districts in order to reflect an electorate that is representative of a state’s population. Prior to 1965, states were able to split minority communities into multiple districts where their votes would be intentionally diluted. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act prohibited states and local governments from drawing or maintaining districts that had a discriminatory impact on voters.[10] However, these protections are currently in jeopardy of being eroded, as the Supreme Court is presently considering whether Alabama’s 2021 redistricting plan should be upheld even though it divides the districts in such a way that makes it impossible for Black voters to elect their preferred candidates.[11]

This inequitable treatment has a chilling effect on voter turnout, especially at the local and state level. If historically disenfranchised voters feel that their voice is intentionally being suppressed to the point that it is impossible to elect their desired representatives, they lose faith in the electoral system and stop participating. At the same time, many voters are fearful that far-right extremists will create chaos and conflict on election day, either by intervening in the election process, encouraging poll workers to violate election law, or intimidating or harassing other voters. In recent years, claims of widespread voter fraud have created an unprecedented skepticism regarding the integrity of our democracy and our electoral process. Some individuals and organizations continue to insist that the 2020 presidential election was “stolen,” “rigged,” or otherwise fraudulent, despite extensive evidence to the contrary. The Brennan Center for Justice found that incidents of voter fraud ranged from just 0.0003% to 0.0025%.[12] However, numerous states have enacted unnecessary, new voting restrictions and created new government entities based on the justification of rampant voting fraud.

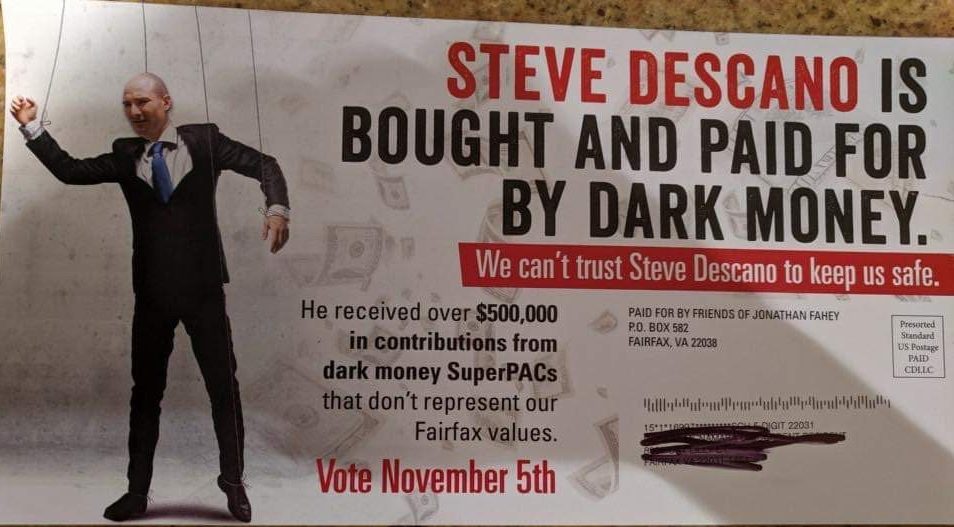

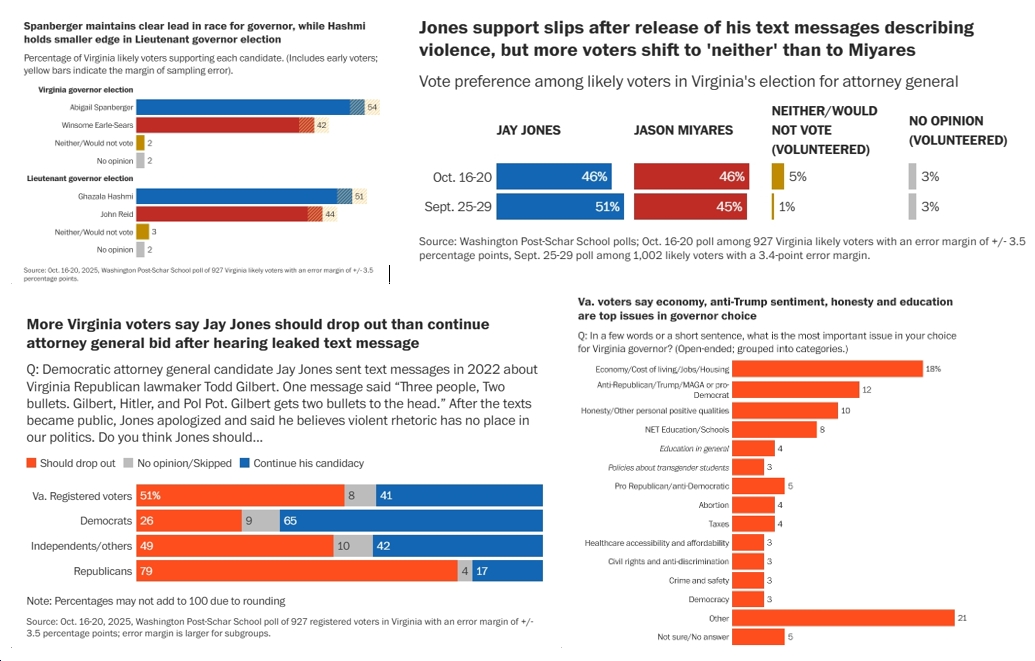

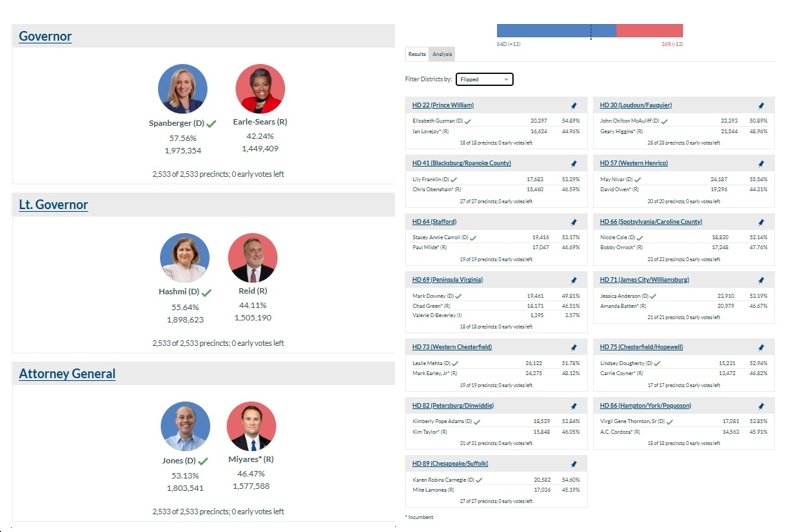

In September of this year, Virginia Attorney General Jason Miyares created the Virginia “Election Integrity Unit,” despite acknowledging, “there was no widespread voter fraud in Virginia or elsewhere in the country.”[13] Taxpayer dollars have been reallocated to finance the new unit, consisting of attorneys, paralegals, and investigators, to “ensure legality and purity in elections.”[14] The official purpose of the unit is “to provide advice, support, and resources to ensure that Virginia election law continues to be applied in a uniform manner, and increase confidence in our state elections.”[15][16] Unfortunately, the creation of this unit and the allocation of significant taxpayer resources, gives the impression that widespread voter fraud continues to be an issue in Virginia, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Attorney General Miyares has emphasized that “[i]t should be easy to vote, and hard to cheat.”[17] Yet he seems to have given little thought to the reality that the threat of prosecution, in itself, may have a chilling effect on voter registration and turnout, especially for low-income Virginians that struggle with housing insecurity and communities of color. It is important to note that the “Integrity Unit” also has the ability to investigate violation of Virginia’s election laws, which clearly make it “unlawful for any person to hinder, intimidate, or interfere” with any qualified voter’s ability to cast their ballot.[18] If the “Integrity Unit” truly wants to build confidence in the electoral process, it should allocate the more attention to protecting qualified voters and addressing misinformation than investigating the extremely rare cases of voting fraud.

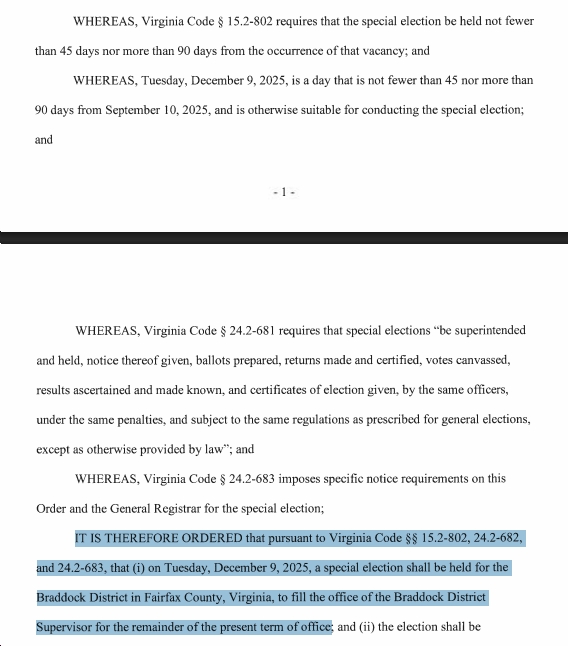

A few weeks ago, voters in multiple towns throughout Fairfax County, including my hometown of Herndon, received redistricting mailing from the county election office that listed the Stacy C Sherwood Community Center in Fairfax City as the ordained precinct polling location. However, Fairfax City is not a part of Fairfax County; it’s an entirely separate jurisdiction with different candidates. Based on this misinformation, it is possible that dozens of voters from Fairfax City will travel to Fairfax County and attempt to vote, only to be turned away. Depending on where you live in Fairfax County, the drive to Fairfax City could take up to 30 minutes. This administrative oversight by the state itself, has already created confusion and could prohibit voters with limited time and resources from reaching their proper polling place on election day. If the Attorney General of Virginia is serious about protecting the integrity of our democracy and restoring confidence in our electoral system, his administration needs investigate the government’s role in disseminating this false and misleading information and take appropriate action.

Make sure you have the correct information for your polling location.[19] Although 100% voter turnout may not be possible, we need as many people as possible to come out and vote if we’d like any hope in our democracy to truly represent the will of the people.[20] If you are turned away on election day, if someone interferes with your ability to vote, or you witness voter intimidation, report it to the appropriate authorities immediately.

Do not let anything or anyone keep you from exercising your constitutional right to vote. There is so much at stake in this year’s mid-term election, including the right to vote itself. I call on all Virginians, regardless of your race, gender, religion, political party, or socio-economic background, to get out to vote on November 8, and at every opportunity thereafter. Let’s vote for candidates who support our right to vote and our human rights. Our ancestors fought so hard to guarantee our ability to participate in our democracy. We cannot let their sacrifices go in vain at this crucial moment in history.

For the sake of our country and the future of our children, we have to consistently exercise our right to vote if we want to improve our society and our country. Change is possible but does not happen overnight. Like Stacey Abrams has said, “voting is like medicine. It’s not magic, we don’t get everything we want when we win one election. Voting is medicine and we gotta keep taking it, and we gotta keep making progress.”

[1] Reconstruction and Rights | Civil War and Reconstruction, 1861-1877 | U.S. History Primary Source Timeline | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress (loc.gov)

[2] Section 4 Of The Voting Rights Act (justice.gov)

[3] Voting Rights Act (1965) | National Archives

[4] Jurisdictions Previously Covered By Section 5 (justice.gov)

[5] 12-96 Shelby County v. Holder (06/25/2013) (supremecourt.gov)

[6] 5 Egregious Voter Suppression Laws from 2021 | Brennan Center for Justice

[7] 16-980 Husted v. A. Philip Randolph Institute (06/11/2018) (supremecourt.gov)

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Guidance under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, 52 U.S.C. 10301, for redistricting and methods of electing government bodies (justice.gov)

[11] Merrill v. Milligan – SCOTUSblog

[12] Briefing_Memo_Debunking_Voter_Fraud_Myth.pdf (brennancenter.org)

[13] https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/10/19/jason-miyares-election-integrity-unit-virginia-fair-elections/

[14] September 9, 2022 – Attorney General Miyares Announces New Election Integrity Unit (state.va.us)

[15] https://www.elections.virginia.gov/resultsreports/registrationturnout-statistics/

[16] https://www.oag.state.va.us/media-center/news-releases/2452-september-9-2022-attorney-general-miyares-announces-new-election-integrity-unit

[17] Id.

[18] Va. Code Ann. § 24.2-607(A) (West).

[19] https://vote.elections.virginia.gov/VoterInformation/Lookup/polling

[20] https://vote.elections.virginia.gov/Registration/DmvLookup