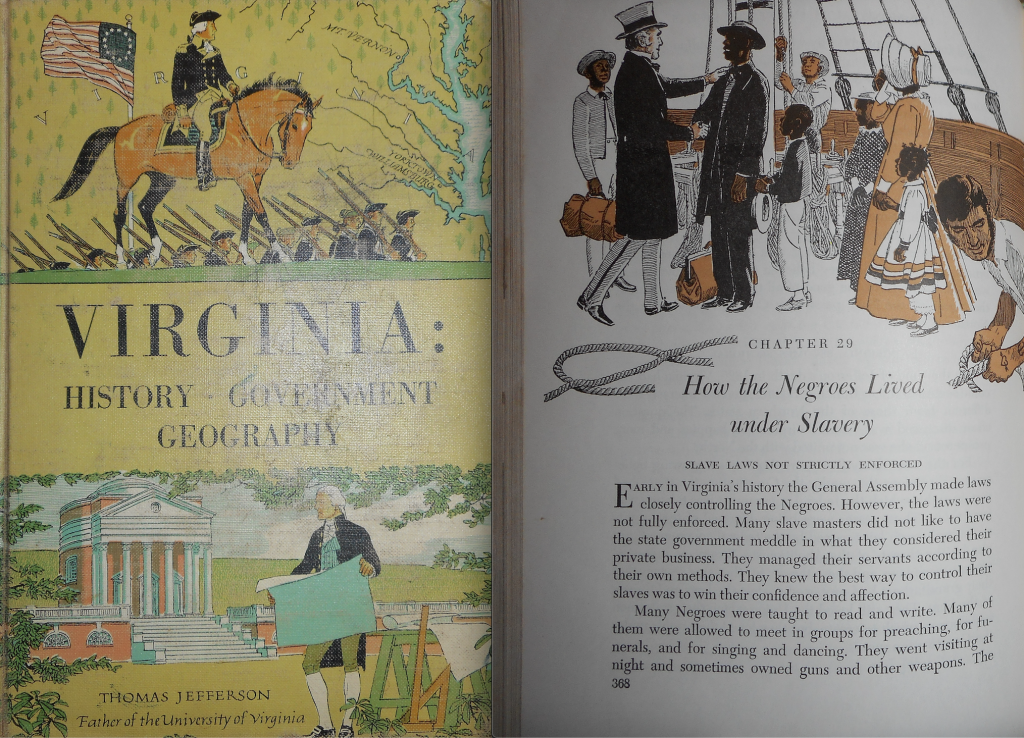

A page from the textbook Virginia: History, Government, Geography, which politicians wrote and state government mandated in public middle schools from the 1950s through the 1970s.

***

The man who is possessed of wealth, who lolls on his sofa or rolls in his carriage, cannot judge of the wants or feelings of the day laborer. The government we mean to erect is intended to last for ages. The landed interest, at present, is prevalent; but in process of time, when we approximate to the states and kingdoms of Europe; when the number of landholders shall be comparatively small, through the various means of trade and manufactures, will not the landed interest be overbalanced in future elections, and unless wisely provided against, what will become of your government? In England, at this day, if elections were open to all classes of people, the property of the landed proprietors would be insecure. An agrarian law would soon take place. If these observations be just, our government ought to secure the permanent interests of the country against innovation. Landholders ought to have a share in the government, to support these invaluable interests and to balance and check the other. They ought to be so constituted as to protect the minority of the opulent against the majority.

—James Madison on the Term of the Senate, Constitutional Convention

The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.

____________________________________________________

The Virginia Way is defined as the dominant ideology of the state’s ruling class. For as far back as we can go, the Virginia Way has been most pernicious not in its clearly self-serving corporate and government public relations functions, but in the insidious dissemination of a false ideology that was and always has been central to the identities of many well-meaning, well-educated Virginians.

There has been a long campaign to convince voters and scholars of the Virginia Way myth of clean government in which examples of corruption are usually dismissed as deviations from a glorious history stretching back to Lee, Jefferson, and Jamestown. These “deviations,” however, are really the main story. At the same time, Virginia politicians ignore plain facts and evident consequences in service of a Virginia Way ideology that just so happens to benefit themselves.

This week’s hagiographic celebration of Jamestown’s founding is merely the most recent manifestation of a consistent pseudo-intellectual lineage. The history of Virginia as the birthplace of democracy and “great men” has long been subject to mythmaking and historical revisionism from those who possess the intellectual gifts and freedom to know better.

To pick just one of countless examples, James Southall Wilson attained the highest honors as the Edgar Allan Poe Professor of English at the University of Virginia, and in 1930, he reviewed The Virginia Plutarch, a collection of essays on thirty-two men and one woman whom the author, Philip Alexander Bruce, felt had the greatest impact on Virginia history. Wilson wrote that Bruce:

“…is himself one of the highest and most exquisite illustrations of the civilization of the old South. He belongs to a generation close enough to the Virginia that ended with the War between the States to know its soul and to be touched with the savor of its tradition, and he comes of a family that was of the bone and sinew of the old aristocracy, and that through ties of blood or of courtesy was linked with the great men of whom he writes. No one less to the manner born could fittingly have lifted a mirror great enough to give the true reflection of Virginia’s Great Tradition, nor could anyone bred in a later generation have felt instinctively the code and the spirit in which his heroes act.”

Compare this with the Richmond Times-Dispatch editorial board’s “salute” of Congressman Eric Cantor in 2014 after he was so despised by his constituents that he became the first House Majority Leader to lose reelection in American history:

“Today’s Op/Ed page features an extraordinary column by an extraordinary human being. Rep. Eric Cantor (R-7th) uses the space as a platform to announce his resignation from the House of Representatives.…Cantor has drawn comfort and strength from sacred texts. “I seek refuge in You, O Lord; may I never be disappointed. As You are beneficent, save me and rescue me; incline Your ear to me and deliver me. Be a sheltering rock for me to which I may always repair; decree my deliverance, for you are my rock and fortress,” the Psalmist says.…Cantor came to the political world naturally. His gifts were displayed early as though he were to the manner born. Young Eric Cantor saw rainbows; throughout his life he has pursued them. We salute him.”

The editorialists did not mention that Cantor’s wife was on the board of directors of Media General, the company that owned the Times-Dispatch.

Or witness the 2018 op-ed from nephew of a state senator and former Dominion employee Gordon Morse titled, “Bill Howell: An Honorable Servant of Virginia,” penned after the former Speaker of the House took what was described as a non-lobbying consultancy at legal powerhouse McGuireWoods despite Virginia’s one-year ban on lobbying for former officials.

“Howell took over as speaker (greatness was thrust upon him, for all intents) at a time of political turmoil and uncertainty, when the commonwealth might well have slipped backwards, sideways and over itself, riven by partisanship.…Howell’s easy wit made him good company. That helped in many ways. After all, you cannot equitably preside over a disputatious room of elected egos without a high measure of amity and patience. Howell unfailingly provided.…In Howell, McGuire Woods [sic] will get an experienced personality more given to managing than being managed. He will tell them what he thinks and where the lines are drawn. He has been living within those lines all his life. His influence might be as much internal as external. In a nutshell, the idea, thus advanced, that Howell simply took this new job to ‘cash in’ is offensive.”

The “great men” view of history advanced in the preceding examples is standard in Virginia history, though things have begun to change as old assumptions are battered against the rocks of serious scholars who were not “to the manner born.” Brent Tarter, founding editor of the Dictionary of Virginia Biography, found that “an unexamined reverence for the [Virginia Way] that Douglas Southall Freeman, Virginius Dabney, and others propagated in the twentieth century allowed a mythic version of the past to constrict the range of options that the state’s political leaders contemplated. That reverence, more importantly, either blinded them and the larger public to the undemocratic features of their government or allowed them to ignore or accept those features as if they were part of the inevitable natural order of things.”

The bipartisan fake history of the Virginia Way was just as damaging as partisan fake news stories. It affected what men whom “greatness was thrust upon” thought of our present society, the responsibilities of government, and the possibilities for public policy and reform. If everything was fine, as they were taught in school and believed as adults, then why change?

Ben Campbell, Rhodes Scholar and author of Richmond’s Unhealed History, said that “because our history has been lied about for so long, we can never get to the point where the truth gets told, so we act as if injustice were an exception to our situation. The fact of the matter is things are not right; they did not start right; they have never been right. If we can start from there, then maybe we can make them right. That is the challenge of our time, and that is why history has to be properly told.”

But the books of the past century lived on in the dogma of this century. How did this happen?

In “Making History in Virginia,” Tarter relates how the reality described by Campbell and contemporary journalists coexisted with the ideological predispositions of Virginia Way apologists. “Beginning with the original narratives of 1607 and for the next three centuries, the writers who interpreted Virginia’s history were the same people who made the history…so infecting historical writing that much that issued from the book publishers in the guise of history was really fiction in disguise.”

How was this fake history disseminated to the public? In the 1950s, a committee of politicians rather than historians edited the mandated textbooks on Virginia history for public school students. The legislators “were not so much attempting to live in the past as acting on and celebrating what they had been taught and had read about that past and what they therefore believed was the truth,” Tarter writes. “Such was the influence of the textbooks and the historical literature that it reinforced in a select population of powerful public persons what they wanted to believe about themselves and their heritage.”

Virginia students had been taught the “Moonlight and Magnolias” history of Freeman, Dabney, and other Virginia Way historians. “Those were the books that the supporters of massive resistance read when they were in school,” and one of many consequences for the overwhelming majority of Virginians was the barbaric discrimination that shaped that society and echoed to the present.

Fred Eichelman explored this case for his dissertation and later wrote:

“One of the authors informed me that she was told not to be concerned with exposing myths; that was the job of college teachers. An author for the high school textbook told me he was forced to put little emphasis on Native Americans and not mention any plights they may have had due to colonial rule. A whole chapter he devoted to them was deleted. He was also forced to deradicalize Nathaniel Bacon, Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry. Any attempt to humanize Jefferson or relate how he was concerned that slavery would divide the nation would be an attack on the aristocracy. In relation to government there was to be no mention of the Byrd Organization or Machine and no mention of poverty or the poor. The Republican Party was to receive little mention with the exception of Abraham Lincoln who triggered the War Between the States. A Democrat commission member admitted that he personally wrote the government section.”

These textbooks, which can only fairly be described as government propaganda, were used in Virginia “from 1957 into the late 1970s.”

At times the degree of deceit in Virginia’s mandated textbooks ramps to Stalinist levels, as in the reprehensible chapter on slavery, which concludes with the section “How the Slaves Felt”:

“Life among the Negroes of Virginia in slavery times was generally happy. The Negroes went about in a cheerful manner making a living for themselves and for those for whom they worked. They were not so unhappy as some Northerners thought they were, nor were they so happy as some Southerners claimed. The Negroes had their problems and their troubles. But they were not worried by the furious arguments going on between Northerners and Southerners over what should be done with them. In fact, they paid little attention to these arguments.”

(There are few copies of this book left in good condition, but thankfully, I was able to find one. I am attaching the short slavery chapter, which has not been fully published in news reports, as a pdf here: Va history textbook – chapter on slavery Look at it.)

Learning selective history holds particular power over young minds, for the worldview of youth can blind and bind the subconscious of all that follows.

In an insightful book from the University of Virginia Press, Charles Dew movingly examined his own Virginia upbringing in The Making of a Racist.

“My training as a Confederate youth had pretty much been completed when I was in my early teens,” he lamented. “Everything I had learned growing up pointed in exactly the same direction.…[A]nyone who thought otherwise was either an arrogant, or ignorant, Yankee or certifiably insane.” We know that learning is natural when we are young—indeed, children cannot not learn—and requires more effort as the years go by. “I could have stopped at this point and remained warm and content in a cocoon,” Dew wrote.

Satirist James Branch Cabell pinpointed this mindset in the character of Senior, Let Me Lie’s graying bloviator: “That which, incessantly, we were taught before reaching manhood we must continue to believe forever in our hearts; so that even should our reason be convinced that some of if not all this teaching was incorrect, our hearts simply do not honor the argument with their attention.”

The “great men” view of history thus became so central to the identities of many Virginians who grew up during the mid- to late twentieth century and earlier that in 2018, someone as smart as Morse did not merely object to the notion that the former Speaker’s move to the state’s most powerful corporate lobbying firm was not in the public interest—a clear enough proposition—but found statement of the idea “offensive.” The Virginia Way presumes politicians’ purity of motive even in the face of countervailing evidence.

Historical mythmaking and revisionism still did not fully explain what Virginians faced well into the twenty-first century; the reception of another remarkable book shone a mirror on Virginia’s character better than anything else. Published in 2010, it told the story of Richmond’s dysfunctional public schools more thoroughly and poignantly than any work ever had or likely ever would. It was as if James Ryan was genetically engineered to write about the problems that ailed Richmond. The son of an adoptive family, and a first-generation college student, he had won a full scholarship to Yale and another to the University of Virginia Law School, where he graduated first in his class, then returned as a professor for fifteen years after clerking for Supreme Court Chief Justice William Rehnquist. He followed this with service as dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. He examined Richmond’s Thomas Jefferson and adjacent Henrico County’s Douglas Freeman public high schools as the foundational case study for America’s modern education system in his first book, Five Miles Away, A World Apart. His sublime description of Richmond’s battle for freedom and justice diagnosed the failure to integrate the city as the preeminent factor in what Frederick Law Olmsted had called Richmond’s most memorable trait, its “failure…in the promises of the past.” Ryan was not a partisan, and he was open to and supportive of solutions ranging across the ideological spectrum.

What was so unusual about this book was that unlike some of the other major works discussed in this chapter, Ryan found an acolyte in Todd Culbertson, who spent forty years, in his own words, “inflicting opinions on readers” as an editorialist for the Richmond Times-Dispatch. The hagiography of former congressman Eric Cantor quoted earlier evinced Culbertson’s typical method, but Culbertson praised Five Miles Away in ten editorials between 2010 and 2013, writing, for example, that it “belongs on the required reading lists of public officials and private citizens seeking to comment on the state of the schools.” After a time, Culbertson understood as well as anyone that his wide audience could not have missed mention of the book in the city’s only daily newspaper. He penned an unforgettable editorial, “Education Book: Vanishing Act”:

“We hoped that Five Miles would capture the local imagination. This is a compelling book about local institutions and local conditions published by Oxford University Press, an unsurpassed academic house. Ryan reports evidence and offers ideas crucial to the education debate not only in Metro Richmond but also throughout Virginia and the entire United States. Ryan has spoken at Virginia Commonwealth University and next month will appear at the University of Richmond. Interested individuals have contacted him. Still, he and his book deserve far more play than they have received. The region’s school officials and other political figures should have welcomed the opportunity to embrace Five Miles or to refute it. They did not—or have not done so with sufficient visibility. The book also seems to have eluded the grasp of many private groups and people identified with the promotion of good schools. All of central Virginia should be talking about Five Miles. The absence of vigor dismays—and fails to flatter the establishment.”

For better or for worse, the paper’s editorialists have traditionally been some of the most revered and powerful people in the state, and though their national influence has waned, their editorials still quickly become conventional wisdom among the tens of thousands of Richmonders who read the paper every morning with their coffee. But in this case, the editorials were repeatedly ignored, as the book was, and continues to be.

Even Ryan’s appointment to the most meritocratic position in the state had no noticeable effect on Richmond’s education conversation. Ryan was, in a word, beloved, and as a measure of his brilliance and integrity, in 2018 he returned from Harvard and assumed a post as the ninth president of the University of Virginia. The most momentous book ever published about Richmond elucidated the city’s most pressing problems, and knowledge of the work and its importance were spread in the most public way to the city’s citizens. The book did indeed hold a mirror to our society: the lesson was that the people in Virginia’s capital who read these editorials and actually could have done something about the problems collectively decided to decline this unprecedented opportunity in thousands of individual, independent decisions.

The legacy of the Virginia Way was much deeper than portraying or perceiving historical falsehoods as facts. The most profound finding from Eichelman’s study was that “one former commission member admitted to me that the goal of the seventh grade book was to ‘make every seventh grader aspire to the colonnaded mansion; and if he can’t get there, make him happy in the cabin.’”

There was a purpose to Virginia Way history: it was designed to instill among the population rose-colored reverence for the Founding Fathers and the Civil War in order to ingrain docility about their current society by repressing the natural human drives for creativity and freedom. Thus, the powerful were kept in power, unchallenged. Reverend Campbell said after his lifetime of service in Richmond that “what I have encountered is this tremendous sense of passivity before human change. I have this image of Patrick Henry standing up in the middle of St. John’s Church in 1775 saying, ‘Give me liberty, or give me death!’ And everybody else goes back and says, ‘Well, I think we’ll just stay a British colony.’”

Native Virginian and Harvard President emeritus Drew Gilpin Faust has a graceful longform essay on Virginia’s historical memory in the current issue of the Atlantic. As a child, she instinctively came to understand the Virginia Way, the dominant narrative of what to think and how to act. Like Charles Dew, and, one suspects, comparatively few others raised in Virginia’s “warm…cocoon” of aristocracy, she woke up when she realized that the moonlights and magnolias mythology was untenable. “For many white southerners of my generation,” she writes, “a life-defining question has been how long it took us to notice.” Virginia’s supposed gentility shows that our indoctrination, our collective unconscious, is not lesser but deeper than that of other states, because our rules are unwritten and unspoken.

“The myth of ‘consent’ required that white people be able to claim—and convince themselves—that black people happily accepted their assigned places… Prejudice was hidden beneath a surface of politeness and civility that scarcely masked the assumption of superiority, of greater intelligence, of entitlement…In its long pursuit of a more genteel white supremacy—a unique Virginia Way of oppression—the state has nurtured the denial, the failure to ‘see’ [race], that Ralph Northam represents. The story of Virginia compels us to recognize how important it is that we open our eyes and actively resist the assumptions and traditions that would obscure our vision. To imagine we are or can be color-blind is to render ourselves history-blind—to ignore realities that have defined us for good and for ill. The Founders embraced both slavery and freedom. We have inherited the legacy, and the cost, of both.”

One would think this might be of some interest in the week of the heralded Jamestown anniversary; however, as predicted by the Virginia Way framework, her important essay, too, has been entirely ignored.

James Branch Cabell wrote:

“The well-born Virginian of our era is not, and has never been, able to look forward. He has not even looked, with any large interest, at his current surroundings. For we were always taught to look backward, toward the glories of which we had been dispossessed at Appomattox.…The dream is the one true reality.”

Virginians lived in a free society, but they were uncommonly burdened by an unseen force in the freedoms they chose to exercise. In 2019, most Virginians, perhaps almost all, may have felt not just that the state’s past was a certain way, but also that they did not have full agency in their own lives to do something about it. When their individual actions added up to a society, the Virginia Way was not “history” as past events: it was a living history and collective unconscious that actively constrained Virginia’s potential in the present.

***

This is the first of a three-part essay on the Virginia Way.

Part 2 – New Threats to Old Powers

Part 3 – Living Faith in Virginia

See also Lowell Feld’s review, “I wrote the book because I believe in the promise of Virginia.”

Jeff Thomas is the author of The Virginia Way: Democracy and Power After 2016, from which this essay is adapted.