We often view others as reflections of ourselves; casting the world we perceive using a mold shaped by limited experience. We shake our heads at outcomes that make no sense in our personal universe and carry on. This perspective arms those, like Jesse Matthew, who, unlike most, would do harm.

We often view others as reflections of ourselves; casting the world we perceive using a mold shaped by limited experience. We shake our heads at outcomes that make no sense in our personal universe and carry on. This perspective arms those, like Jesse Matthew, who, unlike most, would do harm.

In 1999, then Delegate Toddy Puller (D) patroned a bill that established the authority for local jurisdiction review boards empowered to look into fatalities arising from what was then termed domestic violence but is now more broadly designated Intimate Partner Violence (IPV). And while the acts of which Jesse Matthew are accused would not fall under the authority of these boards, the revelations about the circumstances surrounding and those involved in cases like these shed light on how serial offenders are enabled. They speak to the nature of human behavior. One such board, the Monticello Area Domestic Violence Fatality Review Team, recently released its first report.

The product of the review, a fuller context of circumstances leading to fatalities, serves a completely different purpose than that of the justice system. The purpose of fatality review is to determine where in the system something may have gone wrong or whether there is some deficiency that can be remedied to improve services. And instead of shaking heads, this should lead to slapping foreheads, better public policy, and broader perspective.

“…the review reinforces the importance…you actually see…it is when she leaves the relationship that those resources really need to be put in place to keep her safe. It was really an eye-opening time for me, even though I work in this every day…our goal out of having the report is to start generating talk…this is in our community, here is the raw data, here’s numbers and this is what we can work from.” – Robin Hoover, Co-Chair, Monticello Area Domestic Violence Fatality Review Team and Legal Advocate and Outreach Counselor at Shelter.

There is no fine method of painting the landscape of abusive relationships. The rough outline will begin here with those that result in death; the extreme, you may conclude. In my view, that is inaccurate. Tortuous relationships that carry on indeterminately have far greater collateral damage and are more likely to perpetuate.

Isolation and ignorance

Something striking about the IPV cases investigated by the Monticello Area Fatality Review Team is that in every case, no victim had ever accessed available services such as the emergency shelter or the court services unit that issues protective orders. One victim did talk to the police about being afraid, but the concerns she expressed did not rise to the level of anything actionable despite a rather thorough investigation by the police. That did not mean that the fear wasn’t legitimate and wasn’t ultimately borne out, but a crime had not been committed.

In their first case the team found a victim that hadn’t been known to anyone. Her death came as a complete shock to everybody. Her own family did not even know she was married. Isolation is a method of control characteristic in these fatal relationships.

Are there barriers to potential victims of domestic violence coming forward not just to the police but to agencies that can help them and their own families? What the fatality review team found was that it was almost like the victims did not even know the shelter existed. The members of the fatality review team were all perplexed that the victims would not be aware.

Brochures from the shelter are inside courthouses, police station lobbies, hospitals; there is coverage and outreach in local newspapers…but that is the perspective of those on the review board who are by definition immersed in information about resources. They asked, “Do local government and local agencies do enough to make sure that the public is also aware of the shelter?” One of the recommendations in the report is that local governments do everything that can be done using public service announcements and social media to increase awareness of not only the shelter but also other services available. But the reality is that there are barriers that exist in the nature of being the victim of domestic violence that prevent them from coming forward.

Denial and shame

Overcoming the shame that all domestic violence victims feel so that they will be willing to ask for help will always be a tough barrier to overcome. What is telling in the cases studied by this group is how many members of the families were unaware of the violence. Few people outside of the relationship ever know about the violence. Or, those who know choose not to address what they perceive as a very personal matter.

Overcoming the shame that all domestic violence victims feel so that they will be willing to ask for help will always be a tough barrier to overcome. What is telling in the cases studied by this group is how many members of the families were unaware of the violence. Few people outside of the relationship ever know about the violence. Or, those who know choose not to address what they perceive as a very personal matter.

Jon Zug (Assistant Commonwealth’s Attorney, Albemarle County and Co-Chair, Monticello Area Domestic Violence Fatality Team) explains that many people who seek services express that they don’t think that they should be there because “this is for battered women.” Nobody wants to identify as being a victim of domestic violence.

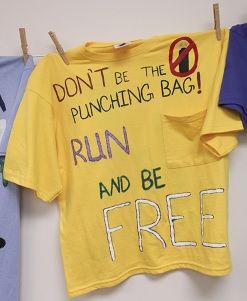

Jon Zug pointed to the “Don’t be the punching bag” t-shirt and related a story:

This is what I hear all the time: “But he didn’t hit me!”

And I’m like, you’re right; I’ve read the report: he…did…not…hit…you. What it says here is that he grabbed you and pushed you down onto the floor.

“Right!”

I say, well, let me ask you a question. If I were to come up to you on the street and do that to you, would you feel like you’ve been assaulted?

“Well, of course…why on earth would you do that?”

I respond, ah, well, that’s a good question. My question is: why is it someone who says they love you…why is it more acceptable that that’s going on with them?

You would think that would be a light bulb moment. It is surprising to me how often that is not a light bulb moment; that because he says he loves me…that is more acceptable. That is something I struggle with, unfortunately, on a daily basis.

Bystanding

The woman mentioned before who had contact with the police never made a petition for a protective order. The team met with a family member of that victim. While that family member felt that the police had not done enough (and he was pretty angry about that) it wasn’t clear what effort the family member made to protect the woman.

A brochure on how to obtain a protective order; a brochure from the shelter; a card that is attached with the contact information for the Commonwealth Attorney’s office, the shelter, social services; this is given to anyone any time there is a suspicion of domestic violence.

It is unusual to have family members come speak to the review team. The advice to these teams is to be very cautious about interviewing family members; to manage the interview very carefully with prepared questions and scripted guidance; the only free-flow was follow-up questions from the responses to the scripted questions. However, this team found the information they gained from the interview very enlightening and that they would continue to include family members going forward. They wanted to interview a family member in a subsequent case with whom a team member from victim-witness had maintained contact over a period of a number of months. But that family member just did not respond to the request, so the team did not persist.

The review team uses a case data collection form as an investigative guide. As they complete the form, they are guided to areas where there are voids in the information. This is where Victim/Witness which may have been working with the family could help fill in the gaps. But the common experience is that any contact with family members is “like pouring lime juice in an open wound” even when the homicide had occurred a decade prior. It has also been their experience that family members blame themselves.

It was clear to me that the family member, despite a total lack of information that had been provided to them from their family member who had passed away really blamed himself. And I didn’t want to do anything…I did everything I could to try to say “that’s not the case” you know…and I remember his parting comment to me was “Well I hope something that I said can help you all in preventing this from happening to somebody else.” – Jon Zug

Robin Hoover argues that the information they gathered actually has helped. It underlines the importance of not only emphasizing with the victims, but also the family members that if they are uncomfortable with the situation they should realize that it may be endangering their lives. In every single case that the team reviewed, the violence occurred either while or after leaving the relationship. In only one of these cases was the divorce final. Of the five, three were in the process of removing themselves from the relationship. The average number attempts by abuse victims to leave before leaving “successfully” is seven. The review team was unable to determine how these cases compared because the relatives (did not reveal or) had not been fully included in the “shameful secret” and the victim was unavailable.

It is obvious that there are issues of some sort when a relationship unravels. Without being privy to details, even as a family member or close friend, making an accurate assessment of any threat is difficult. Standing by may have a couple of effects: it may lead the victim to return to the wrongly perceived relative security of the abusive relationship; it may seal away essential facts permanently when both parties to the relationship perish.

Police don’t go to a murder-suicide, look around and say, “Well it’s pretty clear what happened, so we’re done here.” They do a thorough report that can include information from the perpetrator’s family. It often can go on for weeks and months and tends to take longer than other investigations because there’s no longer a prosecution. However, the report can reveal what the perpetrator has been saying leading up to the murder.

But there are limits to where the fatality review will go. In one case that did not include a suicide, the family members had been enabling the perpetrator, minimizing the behavior, and did not believe he had committed the murder. The team realized that going to them was not going to result in any useful information. In that way, they are even more careful about approaching the family of the perpetrator than that of the victim.

Others aren’t living your life and you’re not living theirs

But it is also a common experience when talking to people in the general public that you get the reaction, “Well, I don’t know anybody at all this has ever happened to.” Of course, you don’t,” Zug remarks. “You don’t know what you don’t know.”

A member of the faculty at Piedmont Community College relates the story of a student of hers who heard Zug lecture in one of her classes last month. After he defined domestic violence in class one evening, that it isn’t just hitting and punching, the student obtained a warrant for her live-in boyfriend the next day.

“The only problem is…she came back to class the next week and told me what she had done, but she hasn’t been back since.”

She called her and discussed her absence and told her that if the domestic violence discussion was just too much shoved in her face (she’d had her head down, crying during class); she should know that they were moving on how to make children safe and elder abuse.

I asked her after she told me about the latest thing “What does your six year old daughter say when daddy and mommy start to fight?”

She said the fight they got into that caused her to go and get the warrant, the little girl just said, “You know, I’ve had enough of this,” and went upstairs to her room.

That’s a six year old.

Zug says that the subject of abuse is one very close to him. There are people in domestic violence situations who don’t ever get hit. Victims who have never been hit have told him there are times they wished their partners would, given how horrible they were to them, just to demonstrate their actions. An abuser may never have to use physical violence because he has total control through only words, demeanor and mannerisms; the way he treats the victim. Nonetheless, that’s domestic violence.

A weighted risk decision

Oftentimes the decision not to seek services isn’t an ignorance or shame issue. It is a weighted risk decision. Victims may realize the heightened danger if they seek a warrant or shelter. In their view they are balancing the consequences based upon perceived (feared) outcomes. Zug acknowledged that of the cases they reviewed, there may have been one situation like that, but not the others. In at least three of the cases, the victim never understood the gravity of their abuser’s potential for violence.

In one of the cases, the victim had sought legal counsel for divorce after separation but did not have the money necessary to file. Confounding the danger, one of the misperceptions of victims is that divorce will solve their problems. They never consider intermediate steps like a protection order or shelter. Rather, they head first to legal services.

One of the areas where more information could be available is from primary care physicians. Here too the team faced a number of dead ends when trying to identify the victims’ physicians. They did have access to emergency room records at Martha Jefferson and UVa Hospitals. However the cases studied occurred before a 2010 policy shift that changed the approach to care and discharge; actively asking questions when there is a suspicion of domestic abuse. This change may assist in subsequent cases.

I know that because I landed in a hospital and a social worker came to me and asked me if it was safe for me to go home. I fell down the stairs…I was really kind of happy as a prosecutor to see some of the work I’ve been doing has had some effect beyond my direct community…they actually made my wife leave the room to make sure it was safe for me to go home. I told them my wife doesn’t do anything half-assed; that if she had done this she’d have finished me off. – Jon Zug

Three out of the five of the cases were murder/suicides. That diminishes the kind of information they can obtain through a pre-sentencing report. They had a great deal of information about one of the offenders because he had a juvenile history. But there can also be probation/parole reports and assessments, substance abuse treatment history, history of depression, or a child-abuse report when growing up. One of the murderers had a felony conviction outside the jurisdiction (outside Virginia) but the team was unable to access that report. If inside Virginia, this team can access the information through District 9 Probation and Parole.

There are obstacles to total and complete information; to obtaining answers to all the questions they ask. So gaps remain even after the inquiry by the team.

…it’s been happening behind closed doors. I’ve been working with a family in a surrounding county that just had a homicide. And… “I had no idea….We thought something might be happening.”

It’s interesting to see that process based upon the findings and how nobody really knows a lot of times. The homicide was the first time anybody thought there was anything wrong. – Robin Hoover

This comes round to some common characteristics of situations where perpetrators manage to commit all sorts of abuse repeatedly and/or over a long period of time without being held accountable. What we can learn from these fatality reviews can provide lessons about personal defense and security across the entire spectrum of human relations; far broader than the stated purpose. Misperception can enable a dangerous reality. That misperception is shaped by the limits of our experience and often results in the “blame the victim” mentality.

Some characteristics of victims/tools of perpetrators:

- Isolation

- Ignorance

- Denial

- Shame

- Bystanding

- Weighted risk decisions

So now I will wrap back to Jesse Matthew and how the abduction and murder of Hannah Graham can have anything to do with these very narrowly defined cases of IPV. I recently met a former member of the Monticello High School faculty who knew Jesse and is familiar with Jesse’s story growing up.

Something he told me about Jesse echoed Jesse’s own mother’s remarks just after he was first named during the investigation into, at that time, the disappearance: “(Jesse’s) a little slow.” As an adolescent, he was clumsy in social situations and very withdrawn around girls. Football was his only route out of what the faculty member perceived as a chaotic family situation and unpromising future. And that situation is very different than that digested by the commercial media, which unfolded a story of concerned parents who moved to the county to provide their son a better environment and opportunity.

That media depiction is not the assessment of people familiar with him. To the contrary, the perception of those who knew him then was that Jesse’s grandmother was acting in loco parentis. In fact, it seems that his father played little or no paternal role. Jesse was neither a gifted student nor socially adept. This does not seem fertile ground for the development of a skilled sociopath. But if you consider the tools outlined above, the degree they are present in any social interaction will vary as widely as circumstances and personalities involved. Though it serves a purpose in criminal investigations, classifying abuse by outcomes is a disservice to potential victims. After all, their abuse isn’t always apparent.

And, of course, contributing to the uninterrupted series of incidents in which Matthew was involved was that there were no dots to connect because they were swept away. It may be in every case where Jesse found himself under scrutiny that the lack of any prior record left those who encountered him with the same serial perception: a quiet, sort of slow, social inept who didn’t understand his behavior was unacceptable. But we really need to hear more from both Liberty and Christopher Newport Universities. Unfortunately, as useful as it might be, there is no similar standing fatality review that occurs after this kind of crime.

Expect this same sort of tactic in the story weaved when and if Matthew eventually comes to trial. Look for the presentation of IQ tests and academic records. There will be the sort of testimony about a personality and behaviors that have successfully provided him defense against the indefensible in the past. And no one will want to admit that they should or could have known or done anything differently.

What I will argue in due course is that there isn’t a decision matrix or filter you can wring anyone through to reliably ascertain their propensity to abuse or violence. Because someone hasn’t acted doesn’t mean they won’t. Because we haven’t observed it does not mean it isn’t. Even victims who experience it often don’t recognize their abuse. Unfortunately, this tells us that every situation we encounter must be assessed through a jaundiced lens (not unlike that used in law enforcement). But most importantly, every incident should be documented.

And consider this: If someone intimately involved with their abuser does not recognize potential peril, can we expect anyone to be able to judge the potential for abuse in someone they have only just met? Recognizing the characteristics of victims and tools of perpetrators may help make wary potential prey.

That is one added value of these reviews. They may do more than inform service providers about reaching victims. Just as importantly and possibly more, maybe it will help those who might otherwise stand by while their friends and loved ones are abused step forward and encourage them to seek professional help.

![[UPDATED with Official Announcement] Audio: VA Del. Dan Helmer Says He’s Running for Congress in the Newly Drawn VA07, Has “the endorsement of 40 [House of Delegates] colleagues”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/helmermontage.jpg)