by Cindy

In the late 1700s in Virginia and the Colonies, if a jury found someone guilty of a felony, such as “mayhem,” larceny, or property offenses, the verdict was read, complete with the sentence that the guilty be “hung by the neck until dead.” The jury played no role in determining the sentence. Despite the harsh and automatic sentence, there were few executions, because cases went through many reviews before going to the jury, juries often acquitted, and mercy was frequently granted after trial, through appeals, judicial pardon, or by the Governor.

Virginia enacted criminal justice reform in 1796, substituting prison for capital punishment for all but first-degree murders, and creating penalty ranges (up to a ten-year maximum). Unlike other Northern states, however, Virginia vested the authority to set sentences with juries, not judges.

Today, Virginia is one of only six states that use jury sentencing.

Why does it matter?

The Virginia Criminal Sentencing Commission (VCSC) provides to judges a range of recommended sentences for any particular offense, but a jury does not have access to this. This results not only in higher sentences on average by juries, but also increases the risk of a wildly out of range sentence. Additionally, judges have the authority to suspend all or part of a defendant’s sentence, while a jury does not have that option.

The 2019 report on jury sentencing from the VCSC shows that while judges concur with the guidelines in 90% of all bench trials, juries only sentence in that range 50% of the time, 37% of the time giving a higher sentence. On average, sentences that exceed the recommendation are 40 months longer.

This has a tremendously chilling effect on the accused’s right to a jury trial. When faced with the decision whether to plead guilty or risk a trial with sentencing by a harsh and unpredictable jury, many defendants will plead guilty even to crimes they did not commit, or even if they know the prosecutor’s case is flimsy. (Although the defendant can request a bench trial rather than a jury, the prosecutor can insist on a jury.) How chilling is the effect? 90% of all felony cases are resolved by guilty pleas, 9% by bench trials, and only 1.3% of all cases result in a jury of one’s peers.

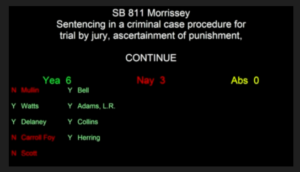

During the 2020 General Assembly session, SB811 (Senator Morrissey) attempted to end this jury penalty, by turning over to the judge the sentencing phase of the jury trial, unless the defendant requests a jury sentence. The bill passed the Senate with bipartisan support. In the House Criminal Justice subcommittee, there was testimony for the bill by a group of progressive Commonwealth’s Attorneys from Northern Virginia and the City of Norfolk; and against the bill by the (more conservative) remainder of the Virginia Association of Commonwealth’s Attorneys. The opposition cited the additional costs of judges and juries that might result from more defendants actually exercising their right to a jury trial, once doing so would no longer be like playing a game of Russian Roulette.

A visibly frustrated Delegate Don Scott asked “How expensive is one day of liberty? Some folks say fairness is expensive, doing the right thing is expensive.” Delegate Jennifer Carroll Foy called it “one of the most impactful and important pieces of criminal justice reform legislation that we could potentially pass this session.” Despite this, Delegate Vivian Watts made a motion to carry it over until next year, saying that it had come up too suddenly, that in her time on the Courts of Justice committee, this was the first time she was hearing about ending jury sentencing. On a 6-3 vote, the bill was carried over.

The Senate Democrats have included this bill in their list of priorities for the August special session, and with good reason. I spoke briefly about this with Ramin Fatehi, Deputy Commonwealth’s Attorney for the City of Norfolk, who testified in that House Criminal Justice subcommittee hearing. He too called this “the single most important criminal justice reform bill in the General Assembly,” explaining that “the specter of a long jury sentence under prosecution threat can put heavy pressure on a defendant to plead guilty and not exercise his right to a trial at all. An accused person’s decision to plead guilty or to ask for a jury of his/her/their peers should be in the hands of an accused person, not compelled by the trial process.”

I asked him whether the increased costs to the Commonwealth were something to be concerned about. He said that while it’s “difficult to predict the exact effect of ending jury sentencing, it is the right thing to do whatever the fiscal costs. Fundamental fairness dictates that we do so.” He speculated that while there would probably be some increase in jury trials, the juries will be shorter without the sentencing phase, there won’t be a chance for jury deadlocks in the sentencing phase, and prosecutors will be forced to examine their cases more closely before deciding to go to trial. Finally, he reiterated “we should not let supposed costs be an impediment to doing the right thing.”

I hope the General Assembly gets this done during the special session. As Delegate Carroll Foy reminded us during the discussion of the bill: “There is no need to study what is fundamentally wrong and unfair. Justice delayed is justice denied.”