The cloak of silence surrounding intimate partner fatalities is nearly impenetrable. Details are buried with the victims. Family members deny evidence of abuse before their very eyes. But partners who have survived and healed provide a window on the methods and complexity of power wielded by their abusers.

The cloak of silence surrounding intimate partner fatalities is nearly impenetrable. Details are buried with the victims. Family members deny evidence of abuse before their very eyes. But partners who have survived and healed provide a window on the methods and complexity of power wielded by their abusers.

What follows are stories told by women who could be your sister, mother, neighbor, or boss. These women came together in October at Charlottesville’s Shelter for Help in Emergency to share their lives; to try to explain and describe how they were bound to their abusers, how they left, and how they continue to suffer though the healing process. Looking at them you would never know what is inside or be able to distinguish them from the staff at the Shelter. These are striking women who you know but who live secret parallel existences; hidden even from themselves.

The stories that follow are at once different and the same. One striking aspect of these is that the methods the abusers employ are from the same kit familiar to anyone who has studied child or elder abuse or, for that matter, financial exploitation of the wealthy in Ponzi schemes. They are just applied in different variations depending upon the situation and prey. If we recognize the tools in the toolkit, then maybe observing them being applied is the red flag to defend ourselves and others. This, as suggested in A Journey Into Intimate Power and Abuse, provides a perspective that hints a “healthy cynicism” is the necessary defense against any form of nefarious advantage.

All of these women were and are like any of us, reaching to achieve their hopes, dreams, and aspirations. What makes us vulnerable is how and when we assign trust. That vulnerability is an aspect of human commerce as is trust. Sociopaths leverage an intuition crafted from their own experiences to recognize prey and know how to “close the sale.”

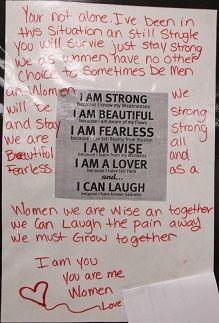

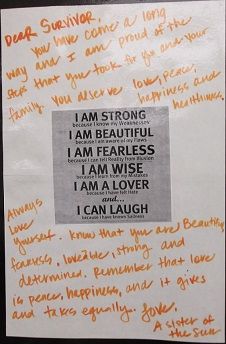

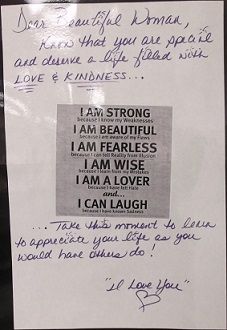

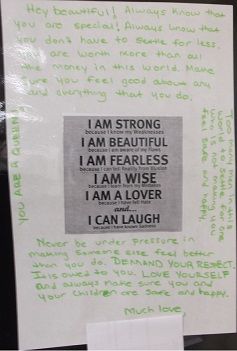

Note: The posters featured here line the walls of the conference room at the Charlottesville Shelter office. Like the stories that follow, there are no names displayed out of respect for the privacy and security of these survivors. (click to embiggen)

The stories are laid out here in much the sequence of the tellers rather than any chronological order. There is a message in that order which is different for each just as each of their tragedies is distinct in detail though not in emotion. The last woman chose someone else’s words to help craft the context for her story.

Alone Far From Home

The first woman, speaking through an interpreter, began her story with a prelude. While living in Houston, Texas she says she suffered domestic violence twice. She called 911 and the police came. Her abuser was taken to jail but was released soon after.

The first woman, speaking through an interpreter, began her story with a prelude. While living in Houston, Texas she says she suffered domestic violence twice. She called 911 and the police came. Her abuser was taken to jail but was released soon after.

In 2009 they arrived in Virginia. She began being treated the same way that she had in Texas the next year. One morning at about 10 am, she was injured when he threw her across a room such that her head struck the corner of a table. She remained unconscious for 45 minutes. Scared that he had killed her, he called the police. The police took him to jail but he was released 3 hours later.

When they went to court, her partner had a lawyer representing him, but she had no one to represent her. His lawyer asked that the protective order be rescinded and unable to understand or speak for herself, it was. After court, a representative from victim-witness spoke to her and gave her a card to call the Shelter if she had another experience of domestic violence.

A year later, he attacked her again, wielding a broken bottle and threatening to cut her face. Afterwards, the woman she was living with at the time called the Shelter. Someone from the shelter came to her house and helped her appeal to the magistrate. From that point on, her abuser was afraid about what might happen to him, so he disappeared. She did get a protective order, but she has never heard from him again.

She attributes her success leaving the abusive situation to the Shelter. The support groups that she has attended have given her renewal and allowed her to escape that cycle. She encourages all who are in such situations to leave; that there is help and assistance. After all that she has gone through, she has been able to obtain a new visa and bring her two daughters from overseas to be a family again.

Compassion and Sorrow for a Ticking Time Bomb

A young woman began her story by expressing her concerns over being a poor public speaker and explaining that she was going to use her victim impact statement to outline her experiences. What she wanted to emphasize from the beginning was her strong desire to convey the emotions involved in staying with an abusive partner. She figures that that is the part which most people can’t “wrap their heads around.”

A victim impact statement, by the way, is an opportunity after conviction and prior to sentencing to explain the circumstances and context of the crime from the eyes of the victim. This particular woman remembered writing the statement was very therapeutic.

She met her partner right after her 15th birthday one January. Like every other 15 year old, she was thrilled to have a boyfriend. They spent time together just like other young couples in what she termed a “normal” relationship. It wasn’t until five or six months into the relationship that things “started getting weird.” But she was young and in love and didn’t really notice. Over the summer break from school they practically spent every day together.

When fall came and school started, he began to mention things he didn’t like. On the first day of her sophomore year he picked out all of her attire for her: a baggy t-shirt, jeans, and a pair of tennis shoes. This was not the fashion she, like any teen, would have chosen, being concerned about what she wore and how she appeared. But she didn’t want to hurt his feelings, so she wore that anyway. After that day he’d ask her, “What are you wearing today?” If it wasn’t something extremely modest, he’d get upset and go into a long spiel about how he thought she was gorgeous and he didn’t want any other guys to look at her. She accepted this as a compliment; her boyfriend thought she was gorgeous and he wanted her all to himself.

Little by little he became more and more possessive over everything. In time he didn’t let her talk to other friends and told her she could not go out with them or even family unless he was along. If she insisted on going out with friends, he became upset and demanded that she text him the entire time, telling her, “I just want to spend time with you and when you are away, I miss you.” She wasn’t allowed to wear her clothes anymore; he made her wear his loose jeans and button-up shirts. Nail polish and make-up were forbidden because “they made me look like a slut.”

He began stalking her to see where she went after she came home from school. Basically she was supposed to sit at home. He would wait in the woods near her house to check on her. If he found out that she had gone somewhere “he didn’t want me to go” he would take her phone and break it so that she couldn’t talk to anyone but him. Her family and friends saw the dramatic change in her. To them she didn’t want to go anywhere, have any fun, or wear her nice clothes.

She doesn’t remember the first time he hit her. There were so many other episodes, more than she can remember; or maybe she had tried so hard to convince herself it wouldn’t happen again. These were always for reasons such as wearing the wrong clothes or going somewhere he forbade her to go. The biggest incident she recalls occurred after he’d been irritated at her for a week because of clothes she’d worn to school. It was on a Saturday and they were on their way to place flowers on her grandmother’s grave. He stopped the truck in the middle of nowhere:

“Get out!”

“Why, what’s wrong?”

“I don’t know. I don’t like you. Just get out of the truck.”

So I got out of the truck…I called a friend of mine and said, “Please come get me.” Then he turned around and came back.

“I’m sorry, get in the truck, please.”

I told him I’d called somebody to come and get me.

He looked at me and said, “You’re going to regret this,” and he sped off and came speeding back at me trying to hit me with the truck. Luckily I was able to jump over an embankment and a fence and the fence kind of protected me from the truck.

There were other times when he would get so upset with her that he would start punching her in the legs and side. “It never felt good, but I kind of just got used to it.” She always knew when it was coming; she knew the look on his face; his jaw muscles tensed up and his hands would form fists. He never did it in front of anyone else. But when they were alone it seemed like everything she said or did would make him angry…he was “like a ticking time bomb.”

After every time he hit her there was always what she calls his crying period. Once he realized what he’d done he would apologize profusely, then turn it on her saying, “If you wouldn’t have done this, then this wouldn’t have happened. You make me so mad that I can’t help myself.” Then he’d start reminiscing about his past and cry. He’d talk about how he didn’t know who his father was; how his mother was never there for him.

“That broke my heart. I started to tell myself that he couldn’t help it. He just needed help and someone to be there for him. The overwhelming sense of compassion and sorrow I felt for him drowned out all the anger, hurt, and frustration that I had.”

Knowing that she could not bear to see him hurt, he used that. By making her feel he was upset, he got out of everything he did to her. When she told him she felt like she couldn’t take it and that she wanted to leave, he took it to extremes, talking about how he didn’t want to live and that there was no reason to if he didn’t have her. There were a couple of times when he came close to ending his life. Riding down the road arguing he started crying and tried to jump out of the truck. She would grab him and plea for him not to jump. There were times when he put a pistol to his head and threatened to pull the trigger. Again, he was manipulating her to act as the conciliator to calm him down.

“The one I’ll always remember: I told him I couldn’t take it anymore and that I realized it was over. It wasn’t two seconds before I had said that that he’d stabbed himself in the chest with a knife he had in his truck. Blood was gushing everywhere, so the thought of me leaving kind of went out the window. I immediately took off my sweatshirt, held it against his chest, and called 911.”

After that she was resigned to staying for him. No matter how miserable she was, she never brought it up. The abuse continued for another three or four months. One morning on the phone he told her that she couldn’t go to church. She was (and is) a deeply religious person. She told him that he could not take that away from her, hung up the phone, and went to church. He met her outside the church with his shirt off in a rage, screaming and coming at her. Fortunately services had not begun so people were still arriving and getting out of their cars. Some of the church members took her inside. That was when it all came out.

It wasn’t then that it got better.

After she was taken to the hospital and her injuries were documented she was able to go before the magistrate. But he was only given 30 days and with “good time” that meant 15. Because she was so confused she wanted to keep talking to him. She was sure he was going to do something. He threatened to kill her parents; he put sugar in her father’s gas tank. But continuing to talk to him just made things worse. At that time, protective orders for dating violence were not available so she got a no contact court order. Eventually he did receive about a year in jail.

During that time, she moved on and was dating someone else. When he got out of jail, he found out about her involvement through social media. One day he broke into her parents’ home. When he knocked on her bedroom door, she thought it was her father and she opened the door. He hit her in the face repeatedly, raped her, and broke her phone. After he left, she called the police. In the old pattern of their relationship he returned and knocked on the door crying. She saw outside that he had broken all the windows in her car. Fortunately she had been better able to respond to the situation than she was before and the police responded.

It was Robin Hoover, the Outreach Counselor at the Shelter that helped her “wrap her mind around the situation.” Hoover not only assisted in court but helped her realize that she didn’t deserve the treatment she had allowed.

“If it wasn’t for the Shelter, honestly, I believe I would probably be dead right now.”

This survivor now has a bachelor’s degree in psychology, a two year old, and is getting married next year. She says things are fine thanks to the Shelter, her parents, and God.

“I know what kind of ice cream I like.”

One woman bears the scars of her experience inside and out. Every day she is reminded by the woman she sees in the mirror. When she thinks about her life what she remembers is molestation at an early age, rape, and dysfunctional family relationships. Her answer was to look for love and she sought it and security in any way possible.

One woman bears the scars of her experience inside and out. Every day she is reminded by the woman she sees in the mirror. When she thinks about her life what she remembers is molestation at an early age, rape, and dysfunctional family relationships. Her answer was to look for love and she sought it and security in any way possible.

When her oldest daughter’s father, who she remembers as her best friend, died she settled on the next best thing, at least in her mind then. He “talked right.” He made a good impression on her parents and she was “at that age where you look to get a husband.” Even after four years of abuse at his hands, she still married him. He had had a child by another woman and she tried to use that to finagle her way out of the relationship before the marriage. But, she says, she was broken and unable to leave; he had her psychologically.

By the day of her wedding she had two daughters and was pregnant with her son. After the long day and the reception they went home. She recalls he wanted some pork chops. Worn out she hesitated. He beat her in her wedding dress. Spousal rape was not recognized at the time so she filed no complaint. Eventually the marriage came apart and he let her go.

Then she fell into another abusive relationship. On April Fools’ Day 1991, doctors at the University of Virginia (UVa) Hospital surgically reconstructed her face. This guy was the same: he could walk and talk with the best of them, but “you don’t know what nightmares are inside.” While she was in the hospital after the surgery her ex-husband came to visit. Saying, “I never beat you like that,” is how he consoled her.

“You have kids you have to feed, so you allow yourself to be in dysfunctional situations. And that is what I did for many years. Can I say that’s the last time I was abused and beaten? No it wasn’t. It took victim advocates four months to get me into court.”

She did go to court, though. He plead guilty in the last 10 minutes before the session, making her sweat it out. He went to jail. It was then she found out he was wanted in several other states.

Because her ex-husband was still around, she moved away. But even away her past haunted her. When a man matching his description was on the loose in Connecticut abusing women she received a call and it all came rushing back. Even on a recent visit to UVa Hospital for an MRI on her foot, she thought back to the reconstructive surgery 23 years ago and again the flood of emotions.

“So that’s what I say my life is like this. I am not a survivor. I live today. I went back to school. I have three degrees: an Associates in business, a Bachelor’s in Psych, and a Masters in counseling. And my life is to tell somebody, you can get up.

And, she says, it is about love. If you can’t look in the mirror and say, “I love me,” you will allow someone else “to come toward you.” People ask her why she hasn’t remarried? She laughs and says, “I am a little selfish now. I know what kind of ice cream I like.”

After one of her beatings someone asked her what kind of ice cream she liked. She realized she didn’t know. She knew what her abuser liked; she knew what her children liked; she had no idea what she liked. And now she knows what it is like to hold her grandchildren and is grateful to have lived for that. “Why do you stay? It’s financial; broken self-esteem; lack of self-love.”

She asks, “Do I love myself perfectly every day? No, I need a manicure now,” laughing. “But I love me a whole lot better than the person who done this to me.”

Recalling that in 1996 she had been celebrated by a local organization for successfully surviving the relationship that put her in the hospital, she sadly relates that she still walked into another abusive relationship. That was when she left Charlottesville, “But you can’t always run, because you are going to be where you run.”

“It took a lot of work, a lot of counseling, a lot of people telling me that you got to love yourself. You have something to give this world. Today, one day at a time, that’s what I try to do.”

“It is the staying gone that is the hardest.”

She begins by asking everyone for patience. She is tearing up and she wipes her eyes. She is eventually able to clear her throat and says, “This is my first time sharing my story ever.”

She begins by asking everyone for patience. She is tearing up and she wipes her eyes. She is eventually able to clear her throat and says, “This is my first time sharing my story ever.”

“I had older brothers and I was a princess. I was very competent; I was very grounded. I knew what I wanted; I knew, “You don’t talk to me that way, you don’t treat me that way.”

And you know my prom date did something I didn’t like the week before prom and I told him to find another date and I called my brother in Arizona and said, “You wouldn’t believe what just happened.”

He locked up his apartment and flew home to take me to prom. That was how we rolled.”

What she wants to express, she explains, is a piece of how the victim mentality just takes over; how you completely lose yourself. For her it is still really fresh and she says it isn’t like you just find yourself out one day. It is very much a journey. It is something she wants to share about her process out “that can help someone maybe you know.”

She married her sweetheart. They started dating when they were young. It was her first serious relationship ever. They had gotten together in high school then broken up for a brief period. During that time she dated someone she refers to as an idiot who “completely broke my heart.” It really shook her. That was the first time that had happened to her and her old sweetheart swept in in a gentlemanly way with the “I can’t believe he treated you that way. You are with me now, these are my boys and we are going to make sure you are respected.”

What she didn’t realize was that he was letting him and his boys take care of her in a way that completely isolated her. Slowly but surely she was separated from her family and friends. She became pregnant. Having been raised that the person you have children with is the one you are supposed to be with, “that was kind of all she wrote.”

From the time she was three months pregnant there was another child in the picture that she was caring for. It was her roommate’s and his. They ended up getting married and had another daughter.

She felt she had to be for him what nobody else was. He was the outcast and she was blond and blue-eyed and pretty; it didn’t matter to her that he was chunky, she saw herself as this magical angel who felt obligated to help him.

She found herself in a little house out in a town that his family owned and ran. It was “to the point that when I called the police they didn’t come.” She says that because things aren’t always as black and white as they seem. People ask, “Why didn’t you call the police?” She did. “Why didn’t you just run?” Because her children were there and he was so incredibly high on meth and so close to the point where he should have had alcohol poisoning that you don’t leave the kids. You do anything you can to keep them quiet. When he is demanding explanations for things that you never even did you are willing to do and say anything so that the children don’t have to see what is going on.

The manipulation starts so slowly, she explains, that you don’t realize what is happening. And she describes the abuser as a master of some torture process where the torturer recognizes when you begin to get a glimpse of reality and does things like keeping you awake all night long; you are taken off kilter to the point everyday life is unmanageable because you have no strength to do more than survive the day. Abusers have a way of knowing how to sap any strength in reserve. It is hard enough to put a game face on for your children and you so desperately want to be present to raise them, acting like everything’s fine. But you are so gone, “checked out” on autopilot in order to live through the situation you are in that you downplay it; to the point you don’t actually see what is happening.

So when people look at you and they’re like, “Don’t you see what’s happening?” No…No I don’t anymore. I don’t see it. Because if I did I don’t think I could go on. And that is not an option because I have kids. You know I am their parent; I am their protector and I am not leaving them behind.

She fast forwards to a day he made her daughter cry; a day she finally left. By that time, all her ribs had been broken at some time or another and she had a permanent black eye. “The typical bodily injuries and things like that.” She still suffers effects from the “truth serums” she was poisoned with: over the counter chemicals and “things like that.”

“It was when he made my daughter cry I said, okay, this is enough. I am setting no kind of example here and I am just going to go. I had the clothes on my back and no money in my pocket at that time because he made me quit my job because I got a radiology scholarship obviously because I was having sex with all the doctors. So I had to quit.”

Gathering up her things, she left while he was at work and went to her mother’s. She thought that was going to be it; that that was the hardest thing she was ever going to have to do. It wasn’t. Stressing to anyone who knows someone doing this, she says to let them know this is only the beginning and that, “I know that if a survivor hadn’t told me, I probably…(starting to sob) I definitely would not be here right now sharing this story with you.”

It is not the initial leaving that is the hardest; you should celebrate it for what it is: a small victory. It is the staying gone that is the hardest.”

Slowly but surely as you begin to recover you realize just how completely destroyed you are. Stopping the pretending and the downplaying is terribly difficult because those are how you have survived and you are naked without them. There is a feeling, even being in a room with people you used to know and used to love, that you are by yourself. Carrying on a normal conversation is sometimes impossible; she began to stutter. When shopping she’d have a full cart then start to think she had everything wrong and put it all back on the shelves. Everything she did, she was sure she did it wrong. She operated out of a complete sense of fear. That was what all her decisions were based upon. It is so hard to undo that and start making choices that will get you to where you want to be.

By that time, trust is not a word that is in your vocabulary, so finding someone you can rely on is impossible when you can’t trust yourself. She hated everything she saw in the mirror for so long. Finding someone who understood her meant finding another survivor who had lived in and could share that “alternate state of mind.” None of what she felt truly made sense to anyone else who hadn’t been through it.

So you can look at me and tell me, “You’re fine. We’re going to help you.” I’m like, no you’re not. You don’t understand. It is so important to have that connection to somebody who does.

That, she says, can help through that process of staying gone, then walk to that place where you can start healing and mending. Having that connection helps get to that place where you make decisions that are not based on fear; not feeling so incredibly broken. Celebrate your victories all along the way.

Remembering filling out her first job application after leaving, she got to the place where they ask for strengths and weaknesses. “I couldn’t fill it out (and I laugh about that now). I don’t have any strengths; I’m not good at anything. It is so frustrating because you feel so numb as you watch yourself, like you are standing outside of yourself.” Watching yourself go through the motions it is like “insert laugh here” and you are supposed to love somebody so it is “insert hug there.”

Building the courage to get back into your body is how she describes the feeling and asks if that makes any sense. Being able to open up and to feel things was scary. “It’s so scary and it takes so much courage.” People who love you get frustrated and wonder why you won’t do things that make perfectly good sense to them. You want to, but you “can’t get back in.” It’s too painful to spend time inside your own body and own mind.

“I remember the first day that I woke up and I got my kids out of bed. And we laughed and danced. I got them ready for school. I did their hair. (her voice breaks) We played. I made them breakfast and we skipped to the school bus. And I kissed them and I hugged them and I put them on the school bus and it drove away. (struggling to remain composed) And it hit me…I love my children…It was the first time I remember I felt that…and it came so naturally…and I can’t quite…I thought I was never going to feel how much I loved my kids and I thought I was never going to be me a good mom and to be me and to give back to them. It was the most beautiful gift to know I was still in there and that it could come out again; that it was going to be okay.”

But it only came after a long struggle and with a great deal of support. It was a fantastic thing she felt and now she is able to repeat it every day. But the journey wasn’t direct. She and her girls’ father shared joint custody for two years.

Never did she think he would lay his hands on them but he did and would hide them from her for periods of time. When she went to pick them up, he would rape her. She was quiet so they would not know. Then when she hesitated to meet him he would turn that on her and say that she didn’t want to see them. One day when she went to pick them up one of the girls had marks on her neck and her step-daughter had been in the hospital. Child Protective Services called her step-daughter’s mother. That was when she found her way to the shelter. That is when her “staying gone” phase ended and her “healing phase” began.

(In the end, he did no jail time for his abuse, but she was able to obtain a no-contact order.)

I wasn’t until the Shelter that she realized “it wasn’t all in my head.” With the support there she was able to start doing things for herself and her children. The therapy and support group empowered her to act on what was best for her; to, piece by piece, put things back together so that she could rebuild.

“I don’t share any of their voices in my head anymore. It’s just mine. And that sounds crazy but it’s a real life thing, okay, if we’re going to get real, to try to do things and hear everybody but you. It’s good to hear my own voice even when it is outside of me.”

Her girls don’t see him when they close their eyes at night anymore. They don’t sleepwalk anymore. They don’t have night terrors anymore. “And they’re happy and they’re incredible and so strong. I tell them every day I want to be like them.”

The therapy continues and she attributes her ability to set goals to the support that provides. But maybe just as or more importantly how to look back on her abuse without those feelings of fear, failure, and self-loathing. She can look back and see her strengths. To her it is not that you just let it go, but that you re-wire yourself to make good decisions going forward.

Please Hear What I’m Not Saying

She doesn’t want her words to fail her so she chooses this poem to explain:

Don’t be fooled by me.

Don’t be fooled by the face I wear

For I wear a mask, a thousand masks,

Masks that I’m afraid to take off

And none of them is me.Pretending is an art that’s second nature with me,

but don’t be fooled,

for God’s sake don’t be fooled.

I give you the impression that I’m secure,

that all is sunny and unruffled with me,

within as well as without,

that confidence is my name and coolness my game,

that the water’s calm and I’m in command

and that I need no one,

but don’t believe me.My surface may be smooth but

my surface is my mask,

ever-varying and ever-concealing.

Beneath lies no complacence.

Beneath lies confusion, and fear, and aloneness.

But I hide this. I don’t want anybody to know it.

I panic at the thought of my weakness exposed.

That’s why I frantically create a mask to hide behind,

a nonchalant sophisticated facade,

to help me pretend,

to shield me from the glance that knows.But such a glance is precisely my salvation,

my only hope, and I know it.

That is, if it is followed by acceptance,

If it is followed by love.

It’s the only thing that can liberate me from myself

from my own self-built prison walls

from the barriers that I so painstakingly erect.

It’s the only thing that will assure me

of what I can’t assure myself,

that I’m really worth something.

But I don’t tell you this. I don’t dare to. I’m afraid to.I’m afraid you’ll think less of me,

that you’ll laugh, and your laugh would kill me.

I’m afraid that deep-down I’m nothing

and that you will see this and reject me.So I play my game, my desperate, pretending game

With a façade of assurance without

And a trembling child within.

So begins the glittering but empty parade of Masks,

And my life becomes a front.

I tell you everything that’s really nothing,

and nothing of what’s everything,

of what’s crying within me.

So when I’m going through my routine

do not be fooled by what I’m saying.

Please listen carefully and try to hear what I’m not saying,

what I’d like to be able to say,

what for survival I need to say,

but what I can’t say.I don’t like hiding.

I don’t like playing superficial phony games.

I want to stop playing them.

I want to be genuine and spontaneous and me

but you’ve got to help me.

You’ve got to hold out your hand

even when that’s the last thing I seem to want.

Only you can wipe away from my eyes

the blank stare of the breathing dead.

Only you can call me into aliveness.

Each time you’re kind, and gentle, and encouraging,

each time you try to understand because you really care,

my heart begins to grow wings —

very small wings,

but wings!With your power to touch me into feeling

you can breathe life into me.

I want you to know that.

I want you to know how important you are to me,

how you can be a creator–an honest-to-God creator —

of the person that is me

if you choose to.

You alone can break down the wall behind which I tremble,

you alone can remove my mask,

you alone can release me from the shadow-world of panic,

from my lonely prison,

if you choose to.

Please choose to.Do not pass me by.

It will not be easy for you.

A long conviction of worthlessness builds strong walls.

The nearer you approach me

the blinder I may strike back.

It’s irrational, but despite what the books may say about man

often I am irrational.

I fight against the very thing I cry out for.

But I am told that love is stronger than strong walls

and in this lies my hope.

Please try to beat down those walls

with firm hands but with gentle hands

for a child is very sensitive.Who am I, you may wonder?

I am someone you know very well.

For I am every man you meet

and I am every woman you meet.

She tells us, “This is special to me because I was sexually abused very young. And I believe this gives an impression of how I carry myself and how I allow people to control me. So it is important to love yourself and to find support wherever you can to help you understand and love and respect yourself.”

For her, that’s the source of it all. We only allow people to do us harm because we don’t care enough about ourselves. So she pleads that if you can remember anything from today, remember that you don’t know anything about what somebody is going through by looking on the outside.

“So anybody that you are kind with, you don’t know how that might bring them out and they might enjoy it. It might be the only joy they ever have.”

When she met her husband in Charlottesville, he opened the door for her and did all the things a man was supposed to do. Then everything became different until there was only mistrust; accusations of things she wasn’t doing. Work was a refuge because there was no peace at home. She was assaulted and he eventually went to jail; she was afraid to go home and found the shelter. Security escorted her from the shelter to her job for months at a time.

She eventually obtained a divorce and says she knows it wasn’t until she went to the shelter that she had the time to clear her mind. And in her mind she believes that the shelter is the only answer for people who are in her situation. In appreciation for the help and support from the Shelter, she does anything she can do to support the shelter.

Hearing what isn’t said; Seeing what isn’t seen

Following their stories, a remark by one of these women made it clear they had only revealed the portions of their stores they thought would reach others like them; the feelings that most of us listening to them just can’t understand. She offhandedly expressed that it was hard enough to talk about without getting into the alcoholism and homelessness. From that you might discern that these vignettes are simply a peek into these tragedies.

Following their stories, a remark by one of these women made it clear they had only revealed the portions of their stores they thought would reach others like them; the feelings that most of us listening to them just can’t understand. She offhandedly expressed that it was hard enough to talk about without getting into the alcoholism and homelessness. From that you might discern that these vignettes are simply a peek into these tragedies.

Of the many things that stand out, one is the woeful absence of family and friends intervening on their behalf. Just as in the cases of intimate partner fatalities, there are obviously bystanders who stood flat-footed, sometimes for years. We have to ask how we can be so blind even when slapped in the face by the facts. Some highly respected people have made that same mistake. James Madison University’s President Jonathan Alger and President Teresa Sullivan of the University of Virginia have been oblivious to the issues of abuse on their campuses. The leadership at Liberty and Christopher Newport Universities seemingly abetted the murders committed by Jesse Matthew. But there may be an even more sorry Virginia case where the University President wanted to act, but was reined in by a narrow minded Board of Trustees.

Not all observers are silent; they just don’t have a seat at the grownups’ table. In “What Intimate Partner Fatality Reviews Reveal” you hear the voice of one witness, the six year old daughter of a victim saying, “You know, I’ve had enough of this.” One mother here speaks of sleepwalking and night terrors. The children know. When there is an argument, they hear it. When their mothers struggle to be quiet while being raped they know the eerie silence is telling. That silence may make it generational. Educators recognize the significance of modeling. Think of the educations these children have received. That silence may make it generational.

While hearing these survivors provides an inkling of why they endured the abuse for so long, it only goes a little way toward describing their tortuous existence and the lengths to which their abusers go in order to keep them bound. One of the tools in the control kit is stalking. Technology has provided a powerful advantage to abusive partners and, as will be discussed subsequently, the Virginia General Assembly has hobbled law enforcement’s efforts to protect abuse victims from their stalkers.

And the purpose of this particular piece? To give voice to abuse victims who stumble across these testimonies and recognize themselves. So that they know if they have left going on those seven times without seeking services they will understand that they are on the verge of being the subject of a fatality review board, if one exists where they die; otherwise just being buried and forgotten except by their children. That they will know it is unlikely anyone who says they love them is going to guide them to the security of their local shelter. That there is refuge and healing if only they just stay gone and learn to love themselves and trust wisely.

![[UPDATED with Official Announcement] Audio: VA Del. Dan Helmer Says He’s Running for Congress in the Newly Drawn VA07, Has “the endorsement of 40 [House of Delegates] colleagues”](https://bluevirginia.us/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/helmermontage.jpg)